I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

When it comes to diving, the main reason that I suit up and jump in the water is for the opportunity to observe fish and other aquatic life.

From dancing rainbow darters and spawning sturgeon to diving ducks, I love it all. Finding anything on a nest is an extra bonus and virtually guaranteed to keep me parked in one spot for an entire dive.

One of our finds is the northern madtom, a small catfish that even the most seasoned angler might struggle to identify. In an earlier column, “No petting for these cats,” I shared how my husband Greg Lashbrook first stumbled upon northern madtoms in the lower St. Clair River.

Northern madtom are one of the species that invests a great deal of effort into their offspring by having the males actively guard their nest sites.

Many types of fish use on a reproductive strategy called broadcast spawning which increases the odds of survival based on sheer volume. For example, a 100-pound female lake sturgeon can release half a million eggs in a single spawning season. She will do her best to deposit the eggs into the gravel substrate to give them the best shot at survival. But the odds are not favorable.

It’s possible that none or only 1 out of the 500,000 eggs the female sturgeon released will survive to adulthood.

Broadcast spawning is a big numbers game, but it’s not the only game that fish play. Many species produce only a small catch of eggs and then dedicate a great deal of energy protecting them, potentially even sacrificing themselves, to ensure some of their offspring survive.

But why should anyone else care about them? And given they are rarely caught or seen, why are they of interest to the Michigan DNR?

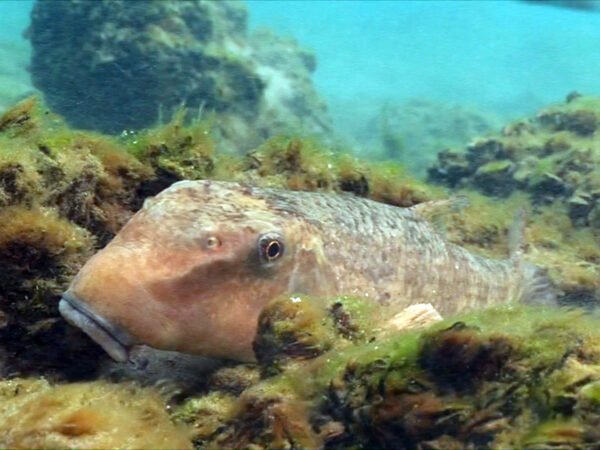

Madtom. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

River Canaries

When a canary in a coal mine stops singing, that is an indication of low-oxygen levels and a signal to get out. The vast majority of us will never enter a mine and yet it is almost universally understood that when the proverbial canary goes silent, you better be heading for the exit.

Many animals provide a real-time indication of what is often unseen. In the St. Clair River, northern madtoms are one of the species that helps researchers gauge the overall health of the river and its inhabitants.

The connection between the dead bird and the lack of oxygen is easy pretty clear. But why catfish, or the lack thereof, is a measure of the river’s health is a little more nuanced.

Maslow’s Madtoms

Maslow’s hierarchy of basic needs can also be applied to northern madtoms. For the catfish to thrive, their basic needs must be met including finding adequate food, suitable shelter, and the ability and opportunity to reproduce.

Food is a basic need of most organisms. Often a determining factor in survival with both native and invasive species is whether they are able to find enough of the right kind of food..

Madtoms eat invertebrates like the tiny shrimp or scuds that live on the bottom, caddisflies being a particular favorite of theirs. For the madtoms to eat well, there must be lots of invertebrates, which means their food supply must be healthy too.

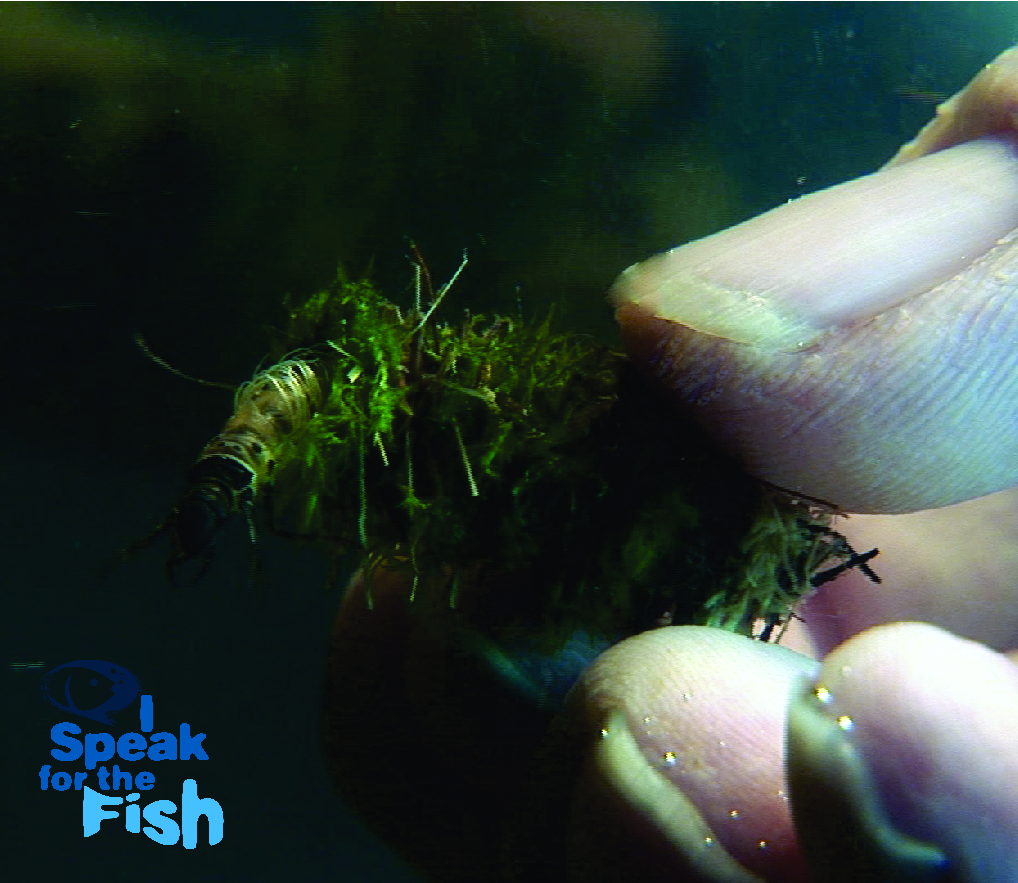

Caddisfly. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

The invertebrates eat some of the tiniest organisms in the system, which are also some of the most sensitive and vulnerable to pollutants. So then, finding large numbers of well-fed madtoms is a good sign that everything down the food chain to the tiniest organisms in the system are doing ok.

Madtoms generally feed at night and spend their days hiding under logs or any cave-like structure. They seem to really like old pickle jars. Flat wooden material like a piece of tree bark with shallow depression underneath and a soft sandy bottom is an ideal nest site.

Madtom habitat is vulnerable to dredging, heavy sediment and even some restoration efforts. Dredging essentially removes the madtoms’ food and shelter. Sediment can blanket the bottom making it difficult for the madtom to find food.

Some restoration projects begin by removing all the “debris” on the bottom and then blanketing the area with clean gravel for “spawning.” A few species such as lake sturgeon use clean gravel to spawn but madtoms do not.

In terms of shelter, northern madtoms need the bottom to have a diverse mix of materials offering lots of protective cover.

To reproduce male madtoms must find suitable nesting habitat, attract a female, and successfully protect the eggs and hatchlings. In the Great Lakes, temperature also plays a key role.

The water needs to be warm enough for the eggs to incubate and hatch properly while still leaving sufficient time in the season for the hatchlings to grow enough to survive the coming winter.

It’s a very, very narrow window.

Madtom egg sac. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

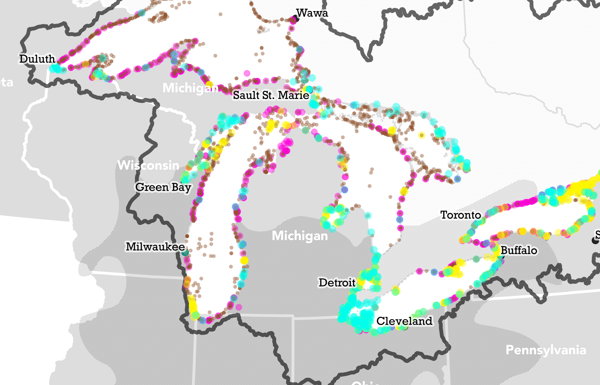

Cold water is one of the biggest factors that limits the northern madtoms’ range. Lake Superior could offer the juiciest caddis flies and choicest catfish condos in the basin but the northern madtoms would not move there. It’s just too cold.

The lower St. Clair River marks the very northernmost edge of the madtoms’ range. The river is not warm enough for the madtoms to nest until about the time the Fourth of July fireworks fill the sky.

Males guard the eggs and hatchlings for about three weeks which means the baby madtom come off the nest around the first of August, giving them only about two months to toughen up for winter.

While surveying lake sturgeon in the St. Clair River, Jan-Michel Hessenauer and Brad Utrup, researcher biologists with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, found a large number of plump and ripe northern madtoms. It was a good indication for the river.

But the researchers wanted to see some males successfully defending their nests before they could say for sure that all was well with the madtoms in the river. To do that, first they would have to learn to scuba dive.

Diving for Madtoms

When Jan and Brad were certified and ready to start looking for madtom nests, they turned to my husband for help.

Greg is one of a very select group of divers in the Great Lakes who can accurately identify a northern madtom underwater. And he is the only diver the researchers trusted to put them on active nest sites in the St. Clair River.

Madtom divers. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Greg was happy to be their guide. He knew exactly where to find an easily accessible, shallow-water northern madtom nesting site.

It was steaming hot in Marysville, Michigan, on the day we met Brad and Jan at the river. The divers were drenched in their own sweat before they reached the water. The DNR tanks were brand new, and their bright neon green was clearly visible as the men sank into the blissfully-cool river.

I could watch their neon cylinders slowing moving upstream until a 40-foot cruiser zoomed past. Its massive wake battered and roiled the shoreline zone until the clear water looked like a chocolate milkshake.

I knew the guys had just gone from being able to clearly see each other to not being able to see their own feet. That’s just one of the challenges of diving in the river on a hot summer day.

Tune into the show to see footage of the northern madtoms guarding their nests and get the researchers’ verdict on the state of the St. Clair River as indicated by a little golden catfish.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Water snakes are spooktacular

I Speak for the Fish: A Fish’s Shelf Life

I Speak for the Fish: A jarring look at gizzard shad

Featured image: Madtom. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)