I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

If you asked me three months ago how I felt about researchers going out and killing fish to put into jars on museum shelves, my answer would have been “They do what now?”

Regular readers will not be surprised to hear that I’m generally opposed to the killing of fish. I did once snap a walleye’s neck, filleted it, fried it and ate it, so I cast no shade on others for doing the same.

Still, if killing fish for human consumption was acceptable, I’m not sure why the idea of killing them to put in a museum made my nose scrunch up — but it did. Until I went and saw one certain collection.

The ROM

Six months ago, I received an invitation to tour the fish collection at the Royal Ontario Museum. Located in Toronto, the ROM is Canada’s largest museum and is comparable to the British Museum in London, England, or the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

The ROM is home to over 13 million artworks, cultural objects and natural history specimens showcased across 40 gallery and exhibition spaces. It’s the kind of museum that you could spend weeks exploring.

My invitation to tour the ROM fish collection was extended by Erling Holms co-author of the Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario, which is my go-to guide for Great Lakes fish.

The Great Lakes Now crew at the Royal Ontario Museum. (Photo Credit: GLN)

The fish collection at the Royal Ontario Museum is one of the top 10 fish collections in North America. It includes 110,000 jars containing about 1.5 million individual specimens spanning more than 7,500 species of fishes. Roughly, one in five species of fish globally are represented, from both freshwater and marine environments.

Due to the volatile nature of the collection – some 100,000 jars filled with flammable liquid — the entire collection is stored off-site from the iconic building in the heart of Toronto.

To show people what it was like, we had a Great Lakes Now crew come along to share the experience with viewers.

Library of life

The non-descript storage facility could have stood in any industrial park in any urban area without drawing a whiff of attention. Nothing about the plain windowless exterior betrayed the extraordinary contents within.

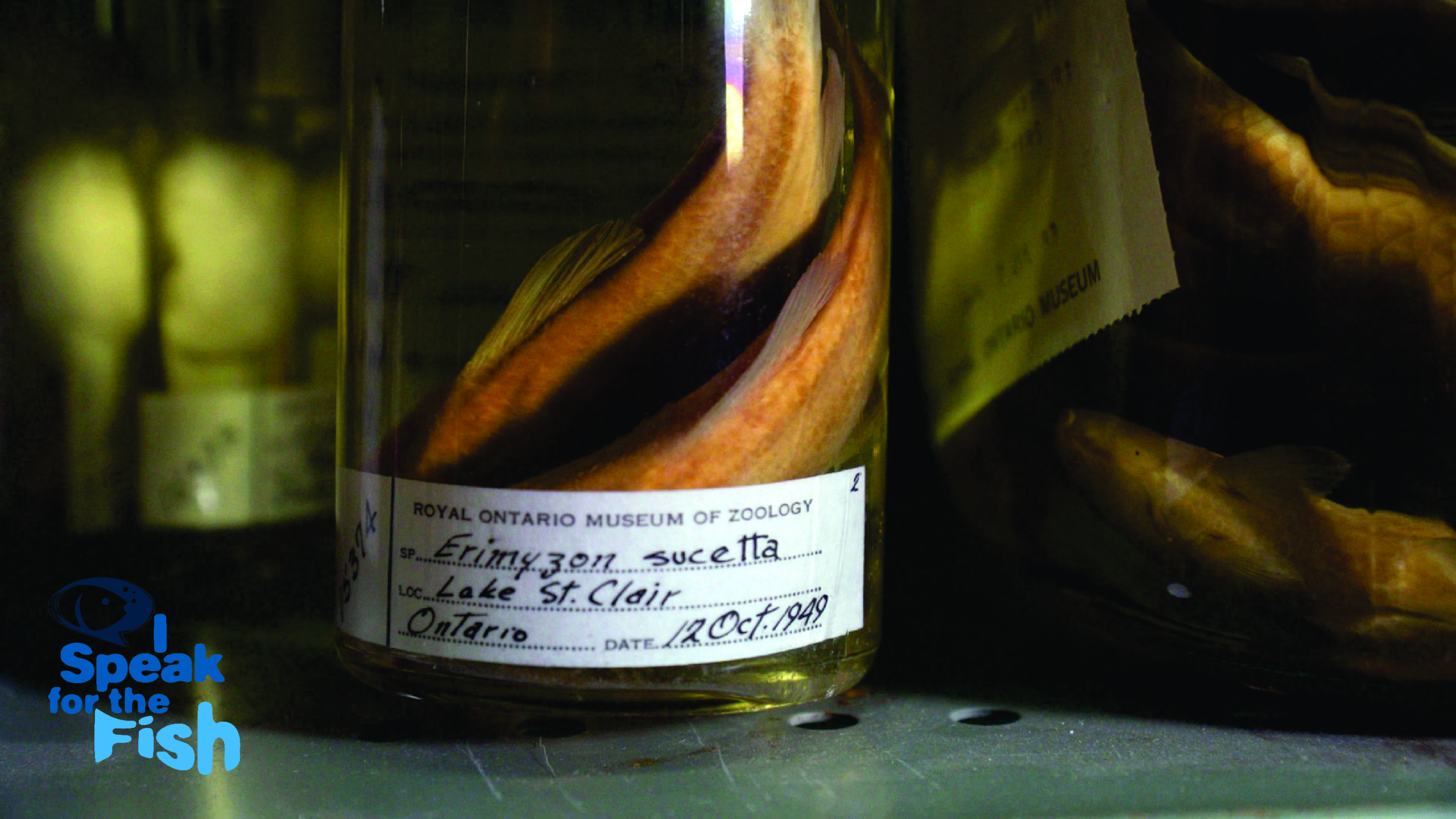

We were escorted to the first collection room which contained row-upon-row of floor-to-ceiling shelves. Each shelf was loaded with glass jars from 3-inches to 3-feet tall. Every jar contained at least one fish suspended in a deep, amber-colored fluid. Some jars held dozens.

Fish collection at the Royal Ontario Museum. (Photo Credit: GLN)

The long rows of vessels were eerily mesmerizing. I found myself wandering up and down the dimly lit aisles pausing occasionally to read a collection label.

Erimyzon sucetta: Lake St Clair, Ontario; 12 Oct. 1949

Erimyzon sucetta: Lake St Clair, Ontario; July 1999

Catostomus commersoni: Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories; 1944

Some jars were tiny like the miniature jelly jars used in edible gift baskets or as a single-serve in some breakfast restaurants. Some of these tiny vessels contained half a dozen or more translucent bodies each barely half an inch long.

A few jars held two to three gallons of preservative in addition to a 20-inch eel or a 2-foot bowfin. The large vessels towered over the majority of the jars which more closely resembled those filling the shelves of the pickle section in every big-box grocery store.

Nathan Lujan, associate curator of the ROM fish collection thinks of the collection as a library of knowledge with each jar being equivalent to a book that can be taken off the shelf, opened and studied.

It was equal parts science-fair-display interesting and horror-film-backdrop creepy.

Brain food

So, why does the ROM store and protect this collection? Why are scientists continuing to collect more? Should they?

I put all of those questions and more to Lujan during my visit. ”Collections like this are the single most important resource for understanding how biodiversity has changed in time,” he said.

I also found a recent article, “Declining growth of natural history collections fails future generations,” published in the peer-reviewed PLOS Biology, where the authors acknowledge that same thought. “Collecting specimens pits two valuable things against each other: the life of a sentient animal versus the knowledge gained by taking that animal’s life.”

So, then what knowledge do collections offer?

One of the primary purposes of the ROM collection is to document changes to fish populations and their ecosystems over time.

Individual specimen stored in a jar. (Photo Credit: GLN)

If rainbow darters are collected from a stream for 100 years and then suddenly none can be found, that is extremely valuable information that researchers and future generations can benefit from having.

The ROM collection is a 165-year-and-counting, record of all the different fish found in the Great Lakes region. At a moment in history when environmental changes are having significant impacts, many researchers question the wisdom of stopping now. It’s a valid point.

But still… can’t they just take a picture? If a picture is worth a thousand words, can one also replace a fish in a jar?

Mug shots

Lujan explained the value in having the actual bodies. One of the first challenges of documenting fish with photography is that fish look very different in the water or floating in fluid than when on the deck of a boat or held in a hand. Capturing an image underwater that provides enough for scientists to make full identifications is extremely difficult at best and often not possible.

Identifying characteristics are not always visible. For instance, some species are only differentiated by the number of teeth in the back of their jaws. Others are distinguished by the number of rays in their dorsal or tail fins which can be difficult to photograph when they are swimming.

But the biggest advantage of a preserved specimen over a photograph, is the ability to apply modern technology to 100-year-old fish. Researchers today are using technologies that were purely science fiction when the ROM collection began in the late 1800s.

Lujan has been using CT scanners to study the anatomy on the inside of fish. He said this technology allows him to see characteristics of the skull and skeleton that speaks to the species’ evolution and ecology.

“It’s just a wealth of information, that photographs would not allow us to delve into it,” he said.

Glass houses

I’m glad I accepted the invitation to tour the collection. Prior to my visit, I found the idea of scientific collecting kind of cringeworthy.

Now, I appreciate how scientists are applying modern technologies to specimens that were collected before most homes in America had electricity and how that research is contributing to our collective understanding of Earth’s biodiversity.

I also appreciate that some people may find the idea of scientific collections completely offensive. I get that too. I just struggle to see the moral high ground when humans kill billions of fish every year for meals and sport. So, if by comparison, a couple of fish sticks are added to the library of life that seems reasonable.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: A jarring look at gizzard shad

I Speak for the Fish: Taking the measure of a rainbow darter

Featured image: Fish species preserved in jars at the Royal Ontario Museum. (Photo Credit: GLN)

2 Comments

-

“I just struggle to see the moral high ground when humans kill billions of fish every year for meals and sport. So, if by comparison, a couple of fish sticks are added to the library of life that seems reasonable.”

That billions (trillions, actually) of fishes are killed for food and ‘fun’, doesn’t justify killing yet more for supposedly scientific reasons. (How many of the countless fishes killed for collections are actually ever even scientifically utilized?)I’m glad if you are “generally opposed to the killing of fish.” However just because you once killed and ate one doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be critical of others for doing the same. It should depend on whether they did so out of necessity or not. If indeed you “speak for the fish,” you should be urging people to have respect, consideration and compassion for them, including by not causing them needless harm.

This includes people working in the scientific field. There has historically been a dearth of consideration in that community for the well-being and lives of nonhuman animals. Concern instead tends to be for populations, with individuals considered expendable (other than those of near extinct species).

A lack of ethics in the catching/killing/collecting of animals for ‘scientific’ pursuits has long been of concern to caring people. Pursuing/obtaining animals in nature can cause environmental problems that negatively affect populations of the species. Catching animals can be extremely stressful to members of their and other communities, and killing them is cruel. We should know about the status of primal human tribes, too, but it would certainly be considered wrong to stalk, catch or kill members of them. We need far greater consideration for nonhuman animals, too.

Just as teaching facilities are finding alternatives to utilizing live animals, so should alternatives be pursued for other institutes. Are existing resources being effectively shared? Are the bodies of captive animals who die in zoos, aquariums, and the like being utilized for such collections? Are animals being killed for the off-chance their remains might be useful or is there actual need? It’s absurd to go killing members of any and all species just in case it might be informative in the future. Could the resources being expended on collecting animals and storing their remains be better spent in addressing the existing hazards that threaten their species? What is desperately needed is compassionate conservation: genuine concern not solely for species but also for the well-being of the individual members of them.

Speaking for the fishes? Plainly, they are not sacrificing themselves for human interests. I believe they instead want to be peacefully left alive in nature, and for humans to fix the problems our species is causing without catching/killing yet more of them.

Mary Finelli

President, Fish Feel -

Where is the comment I submitted yesterday? Are you censoring comments?!