I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

I’m often asked, “What’s the prettiest fish in the Great Lakes?”

As with most things, it depends on your personal aesthetic.

Do you like flowy fins or admire a streamlined form? Are you a sucker for friendly faces or drawn to pleasing hues?

If the aisles of aquarium stores are any indication, color seems to be a key measure of a fish’s desirability.

Sometimes I get the feeling that people think saltwater fish are more colorful than freshwater fish because marine species’ looks have evolved to be more creative or imaginative in the eyes of Mother Nature.

What it really has to do with is the old real-estate adage: location, location, location.

I recently noticed an interesting correlation.

Midwestern Neutrality

Here in the Great Lakes, homes are sided in tan, beige, white, grey and an occasional brick red. But take a drive through the Florida Keys, for example, and you will see houses painted in vibrant shades of pink, purple, blue and canary yellow.

Similarly, most freshwater fish come in shades of silver, white, brown, gold and olive green while their saltwater reef cousins are scarlet, violet, chartreuse and electric blue.

These differences are due to the universal desire, apparently by all species, to blend in with their environment. Great Lakes homes reflect the evergreen, apple, sky and sand tones of the landscape, while tropical homes replicate the orange, lime, parrot, sea and shell colors of their region.

For fish, these palettes apply to survival as the advantages of camouflage underwater are numerous.

Ocean Vibrance

To blend in on a reef, fish have a crayon-box worth of colorful corals, sponges and anemones to mimic. The fish that spend their time cruising in the open ocean all generally have bluish-gray backs and pale bellies to help them to blend in when seen from above or below.

Like the open ocean, freshwater environments have plenty of blue-to-deep-green shades but very few true reds. So, it follows that freshwater fish have evolved to be similarly colored with only a few exceptions.

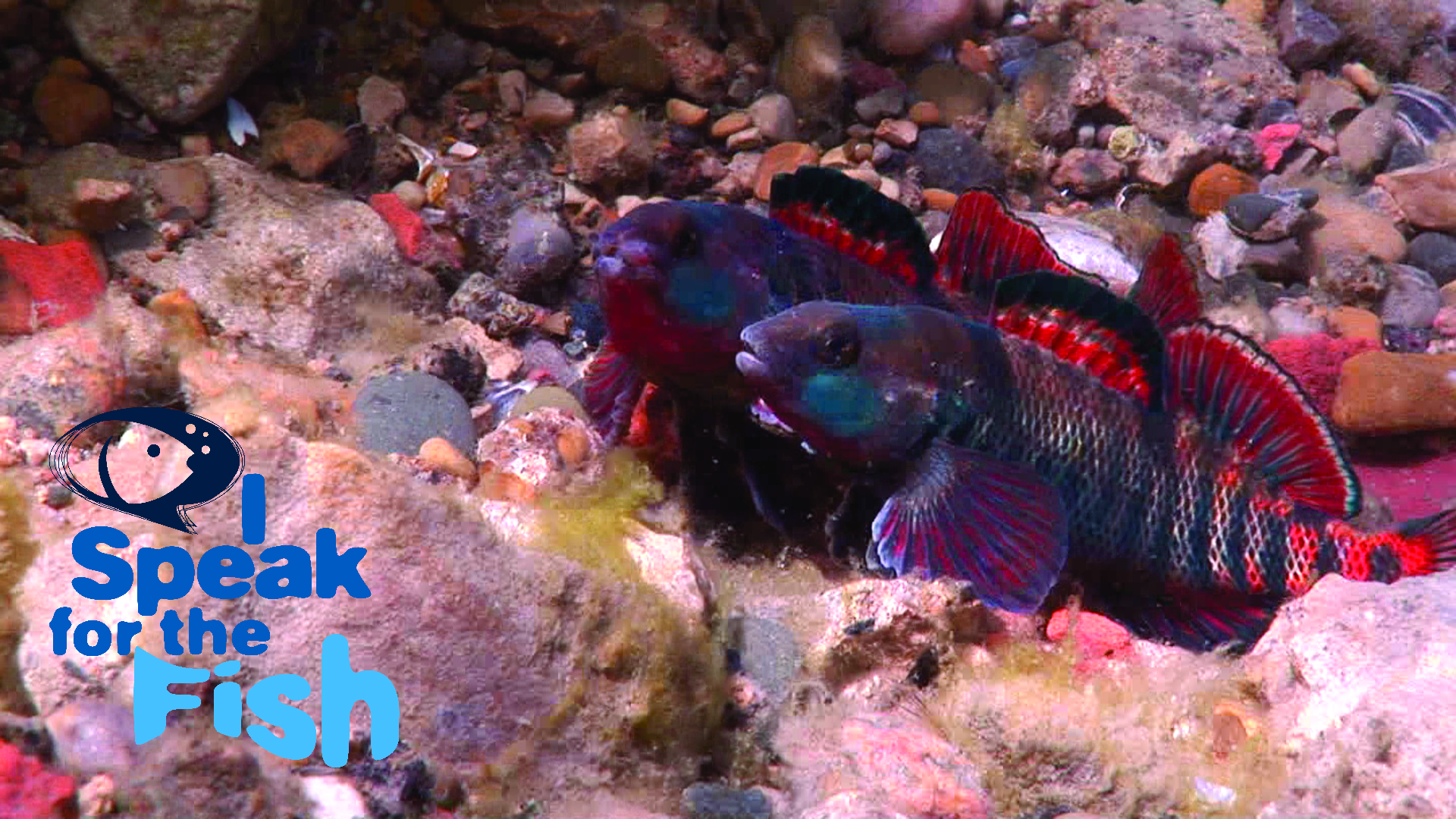

Unlike rainbow trout, whose pink-and-blue coloring closely resembles the pastel tones of sunlight reflecting off raindrops, male rainbow darters are a deeply saturated cobalt blue with candy apple-red highlights.

Breeding males have blue-and-red alternating bars on their sides. Their cheeks and pelvic fins are bright blue while their dorsal and pectoral fins are a deep scarlet rimmed with neon blue. The vivid coloring of the males makes it significantly easier for females to find them.

Males need the bright coloring given the average length of a rainbow darter is a Lilliputian 2 inches, the world record being just 3 inches. The male’s vivid color makes him stand out on a bottom teaming with competing organisms.

Age Matters

Darters are members of the walleye, perch and sauger family and can be found throughout the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins.

There are more darters (186 species) in North America than any other group of freshwater fishes except minnows, according to the ROM Freshwater Fishes of Ontario field guide. But only 12 are found in Ontario.

Apparently, the Great Lakes are a bit too cold and, maybe surprisingly, too young. The ROM field guide notes that most darters like water that is “warm and old (one million + years).” In addition to being cold by almost all standards but Arctic, the Great Lakes are relatively young bodies of water, being just 10,000 years old.

Darters eat insect larvae, crustaceans, mollusks and other critters that live in the substrate.

They are considered an “indicator species,” meaning what happens to darters can reflect environmental changes or conditions in the greater ecosystem. In the darters’ case, because they live and forage at lake bottoms, when pollutants sink and concentrate there, the darters themselves are at higher risk for contamination.

The Fishes of Essex County and Surrounding Waters field guide notes that rainbow darters do not do well in home aquariums. (I’m guessing they were targeted at some point by the aquarium trade due to their brilliant coloration.)

Flared Fins

When males are competing for a female, they take a far more civilized approach than some species.

While male bighorn sheep crash their heads together so violently that the sound can be heard up to a mile away, and bears, lions, and gorillas often leave the mating battleground bloodied and wounded, male rainbow darters take a slightly less aggressive approach.

Typically, in the animal kingdom, the largest and showiest male gets the girl, so to speak, but for rainbow darters it is strictly ladies’ choice.

Spawning males compete for the female by posing in front of her, flaring their dorsal fins and deepening their color.

Typically, one male will be larger, and the smaller males backdown. But occasionally, two males will be similarly sized in which case they have will posture and pose and even measure themselves to prove who is the largest.

Males get side-by-side on the bottom, line up their tails and press the length of their bodies together for an accurate measurement.

Author’s Observation

Beams of sunlight streamed through the clear blue water and bounced off the pebbles on the river bottom. The bands of light shimmered through the water column as the shallow water gently surged back and forth with the rhythm of the incoming waves.

The water was cool enough to feel refreshing on a hot summer day but not cold enough to cause a chill after an hour-long soak.

We happened upon the pair of male rainbow darters shortly after entering the water. Their bright blue and red colors drew our attention immediately. They completely ignored us when we settled in to watch.

A female rainbow darter was also watching them.

The males swam in a tight circle with nose to tail and tail to nose in kind of a yin and yang formation. After about three or four rotations they cozied up for a body measurement. They precisely pressed their tails together, perfectly aligning the ends. Then they pressed their bodies together.

They were exactly the same, at least to my human eye.

Even their coloration was identical. Normally, one will have redder fin rays or a paler blue body, but these guys were a perfect match. In our still images the males are such a perfect mirror image that it almost seems like we used a photo-editing filter.

For the duration of our air supply, we watched the males measure themselves, separate and then try again. Neither seemed willing to accept defeat. And their identical size kept them in a perpetual measurement loop.

I’m bigger.

No, I’m bigger.

No, I am.

One of the disadvantages of being air breathers is that our time underwater is always limited. On each dive we get just a brief glimpse into the underwater realm. It’s not uncommon for us to be out of air before we are ready to go.

On this dive, we drained our tanks watching the males circling and measuring but our time was up, and we had to leave before the female decided which male most favorably measured up.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Industries and public water supplies top list of main consumers of Great Lakes water

Detroit and Toronto among Time Magazine’s “50 Greatest Places”

Featured image: Map of Pennsylvania power plants impacted by the carbon-pricing case.