In Lake Erie, the northern pike occupies, on the grand fish scale of things, a not-so-special place.

The elongated, fast, toothy eating machine is in general neither widely loved nor widely hated. In fact, as far as a sportfish goes, which it most definitely is, it is rather neglected. And in Lake Erie, more so than other Great Lakes, it also may be a victim of early spring weather events.

“This all started when we put a high frequency camera at East Harbor State Park’s Middle Harbor water control structure just to quantify when northern pike and common carp were moving in and out of the system,” said Nathan Stott, a student at Bowling Green State University. “As a part of that we were also trying to look at some of the juvenile northern pike in the area, but what actually happened is we had a really strong seiche that occurred and it happened right as all the eggs were attached to vegetation. It likely wiped out that year class.”

The dike where a new water control structure was installed can be seen here. The channel leading from West Harbor to Lake Erie is at top left. (Provided by James Proffitt)

Middle Harbor, nestled between Catawba Island and the Marblehead Peninsula and entirely contained in East Harbor State Park, was site of an ecological overhaul in 2013. The harbor had been cut off from Lake Erie for decades after a causeway was constructed in the park leading to the beach. The project saw its 350 acres completely drained, re-connected to Lake Erie with a water control structure and planted with native vegetation before being refilled in an effort to make it waterfowl and fish friendly. The two-year project aimed to mostly eliminate rough fish like carp from the site and create new spawning habitat for game fish like bass and northern pike as well as premium habitat for shore birds and migrating waterfowl.

A seiche event is a weather phenomenon that temporarily forces water from one end of Lake Erie to the other.

According to Stott, it was happenstance that he observed the effect of the seiche on Middle Harbor in 2017, giving him the idea for his doctoral research project on northern pike and the extreme fluctuations that affect Lake Erie wetlands.

“So really, my research has been trying to build on that first experience and quantify how much these seiches and the timing of these seiches in the early springtime can really be a driver in the year class strength of northern pike,” he said.

The narrow channel where researcher Nathan Stott tracked northern pike and common carp coming and going in early spring. (Provided by James Proffitt)

Sudden, extreme water level fluctuations

“It occurs when a strong-low pressure system moves northeastward to the west and north of Lake Erie, and as a result very strong southwesterly winds push a large amount of lake water away from Toledo and toward Buffalo, much like water sloshing in a bathtub,” explained Keith Jaszka, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service Cleveland office. “Typically we can see a water level drop of 1 to 2 feet.”

But seiche events can be far more dramatic than just a foot or two in water levels in Lake Erie’s Western Basin. It is not uncommon for residents to wake up in the morning to find boats in marinas sitting in the mud after a 3- or 4-foot water level drop.

During a Nov. 15 seiche, strong, sustained winds sent water levels in Buffalo up 7 feet as water levels in Toledo dropped 7 feet.

According to The Maritime History of the Great Lakes, an 1844 seiche crashed ships in the Buffalo area, washed homes away and drowned 78 people along the far eastern Lake Erie shoreline.

Seiches can cause extreme navigation risks for boaters and lake freighters, as well as inconveniences for residents like flooding and road closures.

“They usually last no more than a day, though if a pressure system is extremely slow moving, they can last longer,” Jaszka said. “The unusually high water levels in Lake Erie have exacerbated the effects of seiches.”

Read more fish and fishing news on Great Lakes Now:

Family-owned fishing businesses displaced by waterfront developments on Great Lakes

Fall Brawl: Sheffield Lake fishing derby inspires intense angling

Carp Advance: Real and potential impacts of invasive fish throughout the Midwest

Already low numbers of northern pike affected

“We actually had 42 northern pike that came into the harbor and something like 836 common carp that came in,” Stott said, explaining that when they removed the camera after about a month, the carp were exponentially increasing. “We could have ended up with thousands of individuals in that Middle Harbor system. There are some days when you can almost walk on top of the carp as long as the waters aren’t fully in the system. They kind of home in on that and they come in heavy from the lake.”

The restoration project aimed in part to eliminate the huge carp presence, since the fish are known to destroy vegetation, rooting along the bottom and creating turbid conditions considered poor habitat for most other fish and waterfowl.

Several plaques around Middle Harbor inform visitors about the recent restoration project. (Provided by James Proffitt)

Stott said the majority of northern pike entered Middle Harbor right around Feb. 22 in 2017, during a sudden warming trend. In subsequent years, Stott said he has found that most northern pike enter Middle Harbor to spawn around March 15. And he has captured and tagged some of them, including one about 37 inches long.

He described early spring seiche events as ecological finks.

“I don’t think they completely wipe out a year class, because you still have fish spawning in rivers and in some other areas where they might be buffered a little bit from the seiche activity, but I do think the years there is not a seiche, they really probably have a really big boom in their year class strength. From some of my age class data, 2012 year class is really dominant. I’d say nearly half the fish I’ve collected are from that year class,” Stott said.

And during that particular early spring spawning period, he noted, there was a three- to four-week window where the water was extremely stable, almost no flow, no seiche.

The significance of seiches relates to the life cycle of northern pike, which find the shallowest and warmest water possible to place eggs.

“As soon as they hatch, they have this sticky little gland on top of their head and they’ll use it to attach to any type of vegetation while they absorb the yolk sac,” Stott said. “As soon as that sac dissolves, they drift off and start exogenous feeding.”

Once they attach to vegetation, the tiny northern pike are stuck. If the water level drops below where the tiny pike are attached, they are exposed and perish.

Future northern pike management in Ohio

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources at one time ran a stocking program for northern pike which saw the fish released into lakes across the state. That program ended three decades ago, so any pike now found in the state’s waters are the product of natural reproduction. Ohio fisheries managers do operate a stocking program of about 20,000 fingerlings annually for northern pikes’ cousin, muskellunge or muskie.

Active management for the pike is not feasible in the open waters of Lake Erie and its tributaries, according to Stott. But there are actions which could help boost spawning success in many marshes.

“I think in some of these connected, diked wetlands, really active management strategies could yield some pretty good results,” he said. “For example, you let all the fish come into a wetland then you stop the movement of water. If there’s a really strong seiche during that time, the eggs don’t get de-watered. At some point you’ll have to open it back up and let the water free-flow.”

This water control structure is where fish movement in and out of Middle Harbor was monitored and which could be used to sequester water during early spring northern pike spawning. (Photo provided by James Proffitt)

Stott said any marsh owners or managers with water control structures have the ability to do this.

“I know the guys at Standing Rush are planning on doing that,” he said. “Places like Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge have sites where they really could do well, too.”

Stott said historically high water levels on Lake Erie have temporarily put the brakes on a series of experiments at regional marshes which could be used to test marsh management efforts directed specifically at northern pike.

Eric Weimer is a fisheries biologist supervisor at the Ohio Division of Wildlife Sandusky Fisheries Station. He said overall, the ODNR’s track record in working with northern pike is not extensive.

“It’s really because they’re so few and far between,” he said. “There are a few locations where anglers catch them along Lake Erie. Metzger Marsh is one, we’ve seen some pictures from Sandusky Bay and East Harbor occasionally, but other than that there’s not many of them.”

Lake Erie northern pike and sportfishing

For Ohio anglers, Weimer described northern pike as something of a bucket-list fish, which anglers would love to reel in but often do not.

“I’m from Michigan and we try our best not to catch them,” Weimer said, laughing. “They really tear up lures. It was always interesting to me how 100 miles can really change your perspective on a fish. I’ve caught maybe one in Ohio.”

If an angler is not targeting “water wolf,” as pike are sometimes called, they can be considered a nuisance.

“I certainly have lost a lot of really nice bass fishing jerk baits and crank baits to northern pike over the years,” Weimer said. “Their sharp teeth, if you’re not using wire leader or a really heavy line, will make short work of monofilament, for sure.”

Weimer said muskellunge are targeted in Ohio far more, especially south of Lake Erie, because of their much larger populations.

“Also, part of it is the allure of the fish. Muskie get much larger than pike, so that’s part of it as well.”

Troy Klingler’s 22.78 pound northern pike caught at an inland lake in 2017. It is the record Ohio northern pike currently. (Photo provided by Outdoor Writers of Ohio)

The Ohio state record for northern pike is 45 inches at 22.78 pounds in 2016. For Muskie? Fifty and one-quarter inches at 55.13 pounds in 1972.

Stott said he believes Lake St. Clair, halfway between lakes Huron and Erie, likely has the densest northern pike population in the Great Lakes. Outside of Lake Erie, northern pike are popular angling targets year-round. They are commonly found in shallower nearshore areas with thick vegetation and other cover. During summer months when water temperatures warm, they tend to seek cooler, deeper haunts.

Chasing and catching big northern pike

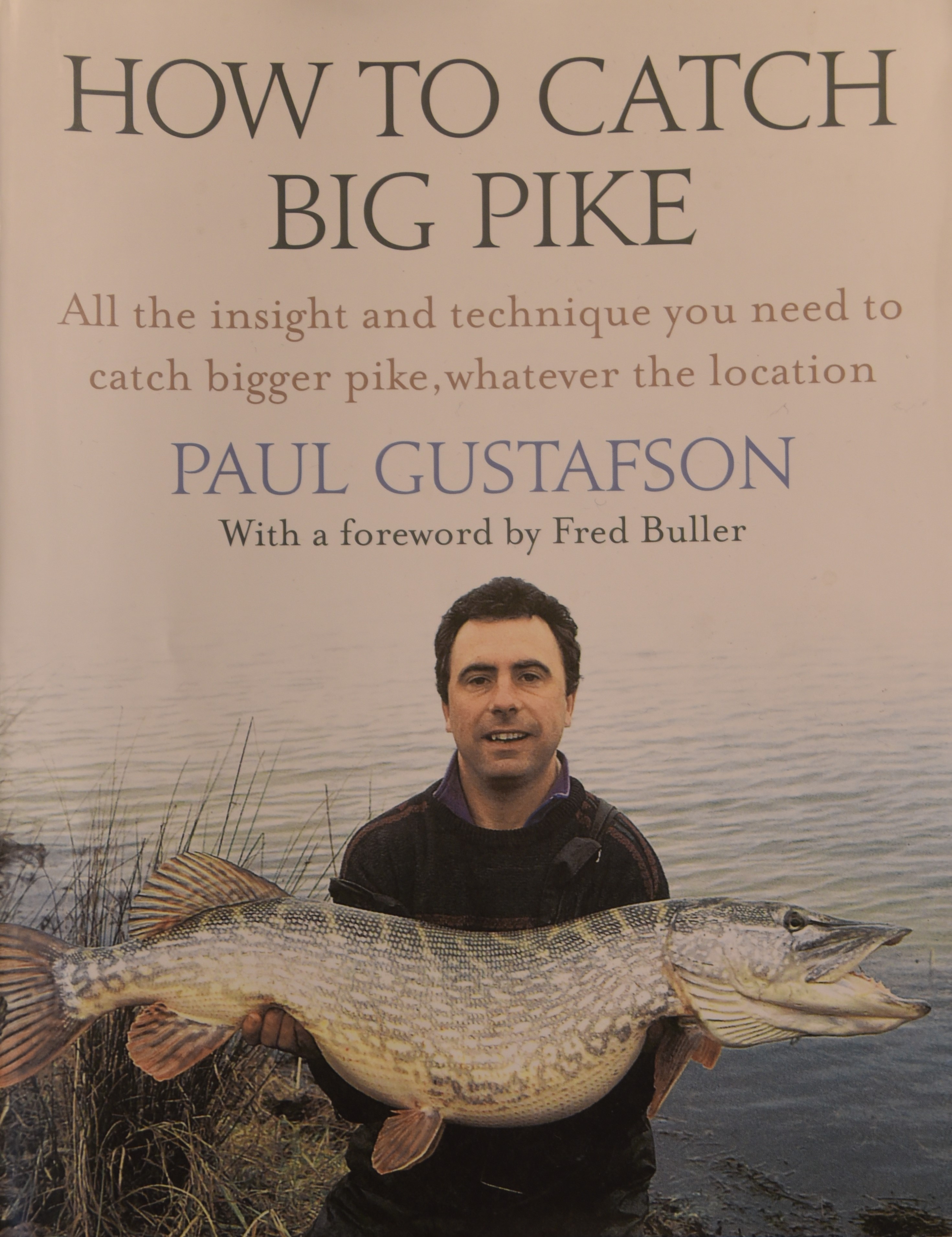

Teaching science and English, combined with a lifelong northern pike obsession, made good preparation for Paul Gustafson’s authorship of How to Catch Big Pike (Hachette). The 300-plus page book is about, well, how to catch big pike. And as much as a how-to fishing guide, it is also a tome on the pike itself, from its habits and quirks to the science behind its eyesight and olfactory senses.

Northern pike-obsessed author Paul Gustafson holding an impressive catch. (Provided by Paul Gustafson)

“I’ve been an angler since the age of 5 and I’ve been pike crazy all my life since I caught a 6-pound pike at the age of 6,” he said. “I did it all by myself and it absolutely frightened me to death. For a little boy that’s quite a big fish, and I had to manhandle it out of the water and take the hook out of its mouth. I’ll admit I got bit on that first occasion – but never again.”

The British angler has landed hundreds of pike from rivers, lakes, lochs, sloughs and ponds in England and across Europe. Northern pike are native to much of the northern half of the central U.S. and most of Canada as well as most of Europe and much of northern Asia.

Gustafson’s zeal for the fish has led him to develop techniques applicable to pike worldwide, based on the science behind the fish that Isaak Walton, one of history’s A-list conservationist once called “the tyrant of the rivers.”

Homing in on northern pike adaptations

“The color receptors in the back of their eyes see reds, greens and yellows better than any other colors,” Gustafson said. “The cornea in the front of the eye doesn’t allow blue light to reach the retina in the back of the eye. I’ve peeled back evidence for the first time from leading fisheries scientists. The tapetum lucidum, a mirror-like gelatinous film in the back of the eye, any light that penetrates the eye is bounced back by this for a second round of absorption. It’s a fantastic adaptation that allows pike to hunt in absolute darkness.”

Northern pike. (Illustration by Ted Knepp. Provided by USFWS.)

Another adaptation, especially useful during fading light and low-light conditions, are specialized rod and cone cells in the rear of the eye which are sensitive to black, white and silver. These cones allow pike to catch prey in all light conditions and in deeper, darker water.

And while vision is an excellent means of locating and ambushing prey, northern pike come outfitted with another system that works in concert to identify and capture food.

A series of pits including both lateral and horizontal lines along a pike’s body lead to ultra-sensitive receptors. Similar structures are located on the head and jaws. If these receptors move, even by as little as 1/1,000th of a millimeter, the pike is alerted to a moving object.

“When any fish moves around a pike’s body or close to a pike, that upsets the water and the pike, through its neuromast organs, bend with water displacement,” Gustafson explained. “The pike, through its neuromast organs, can get the speed, bearing and range of any fish around its body.”

Evidence indicates the fish is more than capable of feeding itself without the aid of sight. He cites a study by a Dutch scientist whereby physically blindfolded pike were able stalkers and consumers of fish. Similarly, a 1988 species report by United Nations food and agriculture biologists says northern pike known to be physically blind were still able to track and eat moving fish using their neuromast system as well as sighted fish.

Where to fish and what to use for northern pike

Bigger is not always better when it comes to tackle selection, but in the case of pike it certainly can be.

“A big pike will always target the biggest prey possible,” said Gustafson. “Targeting the largest fish precludes burning up energy and using energy in the future, so a pike always wants the largest fish. A big pike wants to swallow a big fish and then lay up for a few days and not use up any more valuable energy if it doesn’t have to.”

With that being said, be prepared to spend a few extra bucks for lures specifically targeted at pike, due to their larger sizes. Plugs, crankbaits, buzzbaits, plastic baits, spinners, topwater plugs – all are available pike-size. In addition to artificial baits, live baits are premium too. Any fish that are naturally found in the area make for great pike snacks including perch, larger gizzard shad or shiners, gobies, carp and sunfish. If a northern pike can get a fish inside its mouth, it will eat it.

The use of live bait to “chum” a fishing site is popular in Europe, according to Gustafson, who said the fear factor in baitfish is a serious pike attractant.

“In our research we have found that pike pick up fear pheromones. These chemicals released by a live fish that’s being presented, which pike will home in on,” he said. “What’s interesting, in Sweden we placed live bait in a bucket and put our hands in the bucket. We took the traumatized bait fish out of the bucket, tipped the empty bucket of water into the ice hole, then lowered a live bait. Those fear pheromones, along with the live bait, caught far more pike. The pheromones that live fish put off is very important.”

Water wolves not welcome everywhere

Despite the fact they offer an amazing fight once hooked and for many anglers maybe a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to battle a massive freshwater predator in the U.S., northern pike are considered a threat to the harmonious nature of fish and their environments in many places.

Colorado wildlife officials offer a $20 bounty on northern pike in at least two state reservoirs. The funding is intended to reduce illegally introduced fish and help prevent their spreading to downstream rivers – and the decimation of native fish.

Likewise, California law requires any northern pike caught in the state be killed by removing the head and contacting wildlife officials to report the catch.

Half the length of a northern pike’s head is mouth – a wide, flat, duck-bill-shaped mouth filled with teeth and meant for eating anything that can fit inside. That includes fish, ducklings, birds, reptiles and any mammals which a pike can fit down the hatch.

“They’ll definitely eat anything. You can go on YouTube and type in ‘pike eating’ and you’ll get a whole bunch of videos. They’ll hit ducklings, it’s wild. It’s not very scientific, but you can see it. I know people have found muskrats in their guts when doing diet surveys,” said Stott. “I don’t think that’s prevalent, but they’re very opportunistic.”

Uncommon catches on Lake Erie may have good future

Lifelong Port Clinton-area resident Roger Thompson, whose father retired from East Harbor State Park, has fished the area for decades. During those years he has managed to catch one northern pike, and it came from Middle Harbor.

“I used a float with a large minnow on it, about a three-inch creek chub,” he said. “It was about 26, 27 inches. I’d consider pike around here to be a top-notch gamefish. Really, there’s very few people that realize there’s any pike at all around here.”

Thompson said it took a little while to reel the pike in because his line became entangled in the water lilies and other vegetation, a favorite hunting ground for the fish. Stott said he has targeted pike in the Western Basin and has landed a few.

“It was my first winter here and I was actually trying to catch some northern pike to show them under my camera so I could get a good image for my species validation,” he said. “I wasn’t having much luck electrofishing so I decided to go back to my roots and try tip-up fishing. I caught like five or six in the five or six days we had good ice.”

Weimer, who has landed pike 35-plus inches long in Michigan waters, said the ambush predators are a rewarding quarry – if you’re targeting them and if you’re using good tackle and a wire leader.

“They’re a lot of fun to catch, especially if you’re not losing $10 lures to them. They’re a blast. They’re common in a lot of places, just not Ohio.”

With more wetlands being created, preserved and restored for conservation purposes around Lake Erie and its tributaries, the future may offer new or reclaimed spawning grounds for northern pike. And protection from the increasingly unpredictable weather and water patterns of the Great Lakes. Nathan Stott plans to have more definite answers in about two years.

Read more fish and fishing news on Great Lakes Now:

Dams Across the Great Lakes: End of the line for aging infrastructure?

Shipwreck Life: How fish and other aquatic species utilize Great Lakes shipwrecks

Offshore Decline: Great Lakes fish populations at risk from low nutrient levels

Sturgeon Stocking: COVID-19 puts pause on popular sturgeon release program

Walleye: Lake Erie population skyrockets. Again.

Featured image: This causeway built decades ago kept Middle Harbor separated from East Harbor and Lake Erie until the restoration project. (Provided by James Proffitt)