An estimated 9,887 metric tonnes (22 million pounds) of plastics make their way into the Great Lakes every year. Now a new project aims not only to suck out some of that plastic but stop it from getting into the lakes in the first place.

It began last summer with Toronto Harbour’s installation of three Seabins – devices that look like trash cans in the water but behave like vacuum cleaners, said Christopher Hilkene, CEO of Pollution Probe.

The Toronto-based environmental group is part of a coalition of organizations working to install Seabins at 23 Canadian marinas along the Great Lakes by the end of October.

It is, according to Council of the Great Lakes Region CEO Mark Fisher, the single largest deployment of Seabins in a freshwater system in the world. The council, along with the University of Toronto’s Trash Team and the Boating Ontario Association, are also partners in the project they’re calling the Great Lakes Plastic Cleanup.

Not only is the coalition installing Seabins at marinas, it is also installing storm drain filters called Littatraps to catch debris from storm water before it flows into the lakes.

The initiative is currently focused on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes because the GLPC’s funders are based in Canada – including Environment and Climate Change Canada and Nova Chemicals. Late in October, the Ontario government announced additional funding.

The partners hope to begin placing the devices in high-traffic marinas on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes next year. The Australian-made Seabins and New Zealand-made Littatraps can already be found in some California and Florida ocean marinas.

While marina staff generally dispose of the filtered plastics in garbage cans – the contents of which end up in landfills – the plastics are at least diverted from the Great Lakes, said Hilkene. Various studies have found fish, aquatic birds and bugs ingest floating plastic, which are made of petroleum-based chemicals that can be harmful. Since the Great Lakes are a source of drinking water for more than 30 million people, these floating plastics could also have an impact on human health.

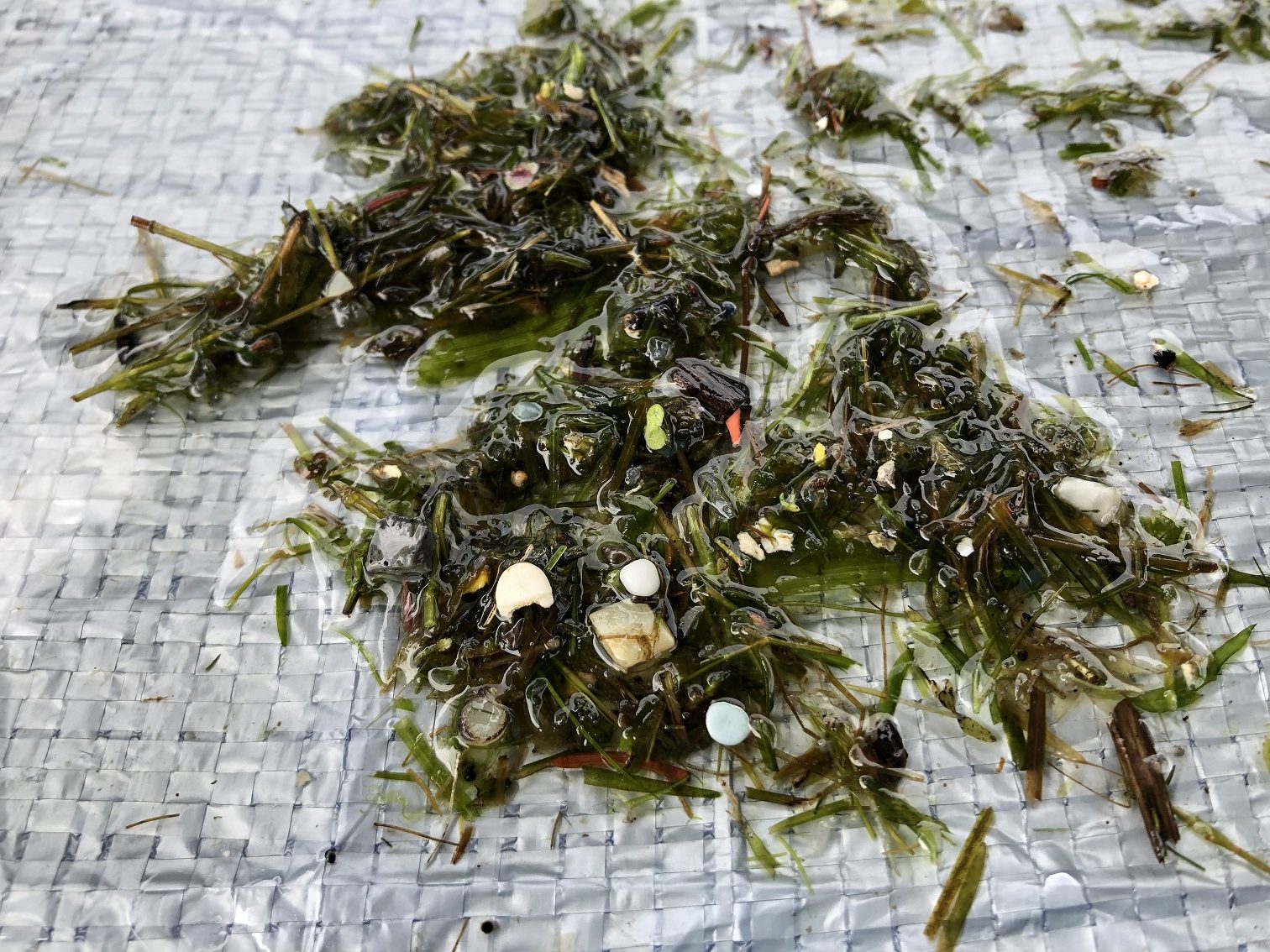

Plastic debris and vegetation from a Toronto Harbour Seabin (Photo courtesy of University of Toronto’s Trash Team)

Beyond plastic diversion

The project is “just one part of a much larger picture,” said Fisher. The partners are developing a government and industry lobby campaign around reducing, reusing and recycling plastics so they don’t end up in our waterways. Once pandemic restrictions lift, they also plan to create a series of educational sessions for the public at participating marinas.

“Only about 9% of plastics are recycled in Michigan, and in Ontario it’s not much better,” said Fisher. “We need extended producer responsibility and recycled content standards.”

The project also has a research component. Some marina operators are mailing plastic collected from both devices to the University of Toronto’s Trash Team for analysis.

Rafaela Gutierrez, a University of Toronto post-doc student who is helping lead the effort, is working on classification standards for sorting the collected plastic – films, food wrappers, fragments. This will help give a clearer picture of what kind of plastics are in the Great Lakes.

“This data will be synthesized and freely available on the GLPC website to alert the world in real time about this issue,” said Gutierrez. “It will also be used to inform future policies aimed at reducing plastic pollution.”

She and her team already have some information from last year’s Toronto Harbour project. Each Seabin collected, on average, 0.023kg (0.8 ounces) of plastic over a 24-hour period.

The most commonly found large pieces were wrappers, fragments and cigarette butts. The most common small pieces were fragments, plastic foam and pre-production pellets, the raw material used by manufacturers of plastic-based products.

The pellets, considered microplastics because they are five millimeters (0.2 inch) or smaller, usually end up in the lakes after being spilled during transport. In October 2018, Western University researchers found pellets in Lake Superior sediments that came from a train derailment a decade earlier near the Nipigon River, a tributary of Lake Superior.

Read more news on plastic on Great Lakes Now:

Banned: Canada takes next step toward zero plastic waste by 2030

Unchanged Mission: Activists say a Nestle Great Lakes exit doesn’t resolve bottled water issue

Chemical Hitchhikers: Great Lakes microplastics may increase risk of PFAS contaminants in food web

Balloon Effect: Survey highlights Great Lakes’ balloon pollution problem

Plastic Permanence: Research shows plastic becoming part of Great Lakes lakebed

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: University of Toronto’s Rafaela Gutierrez pulls debris from a Seabin at Toronto’s Harbour. (Photo courtesy of University of Toronto’s Trash Team)