“The largest land, water and wildlife conservation program for private land owners in the nation”

Its formal name is the Agricultural Act of 2014.

Refer to it as the Agricultural Act, and you’ll likely elicit blank stares. Its predecessor was called by the equally bland name: the Food, Conservation and Energy Act.

But call it the Farm Bill and people may say, yeah, that’s the law that subsidizes farmers. Or it provides food stamps to the needy.

It’s all of those things and more, but Marc Smith sees it from a different perspective.

It’s “the largest land, water and wildlife conservation program for private land owners in the nation,” Smith told Great Lakes Now.

It’s “the largest land, water and wildlife conservation program for private land owners in the nation,” Smith told Great Lakes Now.

And it’s “fundamentally important for clean drinking water,” according to Smith who is Director of Conservation Partnerships at the National Wildlife Federation’s Great Lakes office in Ann Arbor.

Smith worked for clean water protection on the 2014 bill and will have the same role in 2018.

The Farm Bill is up for renewal this year and that’s a big deal for conservation efforts nationally and in the Great Lakes region.

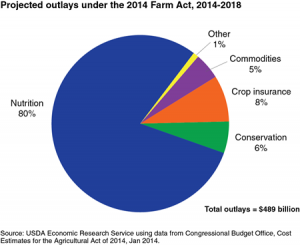

Congress allocates about $6 billion a year for conservation programs in the Farm Bill. That’s six per cent of the total outlay.

“Original stewards of the land”

Why are we spending those billions of dollars to coax farmers to take care of the land?

After all, it’s common practice for farmers to refer to themselves as “the original stewards of the land.” Implied is that they work the land and will take care of it.

It’s not that simple.

Farmers want to protect the land that provides for their income and takes care of their families. But what happens on the land also impacts nearby water.

Farming is a business and businesses have to make hard decisions about priorities. One of them is about balancing production – revenue — with the need for conservation – protecting the environment, an expense.

The two can be at odds.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s website addresses the issue this way:

“Some farming practices can degrade natural resources and the environment. Sediment, nutrient, and pesticide runoff and leaching, for example, can impair water quality. Other practices can preserve and enhance our natural heritage and provide substantial benefits through careful management of agricultural land,” the site says.

The USDA site says the Farm Bill’s conservation programs are designed to “help agricultural producers improve their environmental performance affecting soil quality, water quality, air quality, wildlife habitat, and greenhouse gas emissions.”

Thus, the payments to farmers when they do the right thing by the land and water. Simply put, farmers can be paid to not pollute.

That’s not the norm. We generally levy a fine on industries when they pollute without permission.

Toledo water crisis

Back to Marc Smith’s statement on clean drinking water.

There is perhaps no better example of the clash between farm pollution and safe drinking water than Toledo, Ohio.

In August of 2014 greater Toledo’s 400,000 residents went without drinking water for three days. A toxic algae bloom attributable to nutrient runoff from farms was the culprit.

That singular event put a huge spotlight on agricultural practices related to safe drinking water and that spotlight still shines today.

You see, farmers aren’t regulated like industrial polluters – the industries with a pipe coming from a factory carrying pollutants to a waterway.

No, as a society we’re loathe to impose regulations on farmers, and that applies to Democratic and Republican administrations.

Farmers still hold a special place in our minds because they feed us and, remember that “original stewards of the land” phrase? It’s oft-repeated and still resonates with many.

We deal with agricultural pollution by incentivizing – paying – farmers to employ practices that reduce or minimize pollutants from their land that flow to streams, rivers and lakes – our drinking water sources.

The USDA website lists a “Portfolio of Incentive Programs” rife with acronyms like EQIP, which “provides financial assistance to farmers who adopt or install conservation practices on land in agricultural production.”

Another is CSP which “supports ongoing and new conservation efforts for producers who meet stewardship requirements on working agricultural and forest lands.”

The complete list is here and these are voluntary programs.

Billions spent, few results

Determining effectiveness of these programs is a vexing problem.

A 2017 Associated Press report on farm pollution and money spent to prevent it said “government agencies have spent billions of dollars and produced countless studies on the problem…. but found little to show for their efforts.”

The report said algae-causing nutrient runoff that flows to waterways is increasing and only a small minority of farmers participate in federal conservation programs.

In the Great Lakes region, the Great Lakes Commission is looking at the effectiveness $100 million that has been paid to farmers since 2010 to voluntarily adopt conservation practices.

The commission’s website says “there has been no effort to date to look at whether farmers are responding to these incentives and changing their practices as a result.”

Since 2010 when the payments started there have been blooms in Lake Erie every year with 2011, 2015 and 2017 among the largest.

Marc Smith points out that an improvement in the 2014 Farm Bill was that some payments to farmers were dependent on using conservation practices.

The 2014 Farm Bill process was protracted as it featured a comprehensive overhaul.

There’s potential that the 2018 version could move faster if there are only tweaks at the margins. But that’s not a given. If one group or region wants significant changes others could demand revisions and the process could slow to a crawl.

And a deeply-divided and marginally functioning Congress doesn’t bode well for quick action on the bill. Though a desire for legislators to be able to go back to their states and districts with an accomplishment for the November elections could be an incentive to complete the bill.

The Great Lakes region has a significant player in the process in Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabenow. Stabenow is the ranking member on the Senate Agriculture Committee which will produce a bill with its House counterpart.

Whatever the outcome, the 2018 Farm Bill will impact drinking water quality. For better or worse is to be determined.

The current farm Bill expires in September.

From Great Lakes Bureau Chief Mary Ellen Geist: Great Lakes Now will track the Farm Bill as it goes through legislative process and report on the conservation provisions.