Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

Contradicting the historical conservation planning tenet that gave preference to protecting larger, more intact areas, a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science has shown that small, isolated patches of habitat are inordinately important for biodiversity conservation.

The bottom line is that large habitat tracts are important – but so are small ones.

This analysis of 31 conservation case studies from 28 countries around the world found that if conservationists gave up on small patches of habitat, we would stand to lose many species that are confined to those environments, and biodiversity would decline as a result. These researchers concluded that we should rethink the way we prioritize conservation to recognize the critical role that small, isolated patches play in conserving the world’s biodiversity. Restoring and reconnecting small, isolated habitat patches should be an immediate conservation priority.

Chicago Wilderness is a good example of an effort linking small- and medium-sized habitat tracts into a large conservation network that spans four states – Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan. This program may sound like a misnomer in the greater Chicago area, but their network of fragmented preserves has been incredibly successful. More than 260 public and private partners are involved in restoring, protecting and connecting distinct habitats through conservation and thoughtful sustainable development practices.

Members and volunteers plant a pollinator garden at St. Philip Lutheran Church in Trenton, Mich. (Photo Credit: John Hartig)

Biodiversity is the variety of life in the world or in a particular habitat or ecosystem. In general, the higher the biodiversity, the healthier the habitat is for all of the species living there. That’s important because each of us has a sense of habitat. It is the place where an organism makes its home. A habitat meets all the environmental conditions a plant or animal needs to survive.

Dr. John E. Gannon, scientist emeritus at the International Joint Commission, remarked:

Sure, it’s best whenever possible to preserve large tracts of habitats with corridors that connect to other habitats, but that is often not possible in an urban setting. Seeing the picture of the beaver on the Detroit Riverwalk that is now residing in the Milliken State Park wetlands is testimony that creating and preserving small fragments of habitats are important.

Another good example of small-scale habitat restoration is the work of Detroit Audubon under its Detroit Bird City initiative. Their goal is to restore and protect habitat for birds, while making nature part of everyday urban life.

The Detroit area is well known for its birds primarily because it sits along the Detroit River and other connecting waterways that are at the intersection of the Atlantic and Mississippi flyways. Detroit Audubon volunteers have identified over 350 species of bird in the metropolitan area.

For years, Callahan Park on Detroit’s east side was just another empty space, abandoned and often used as a dumping ground for trash. Detroit Audubon worked with the city of Detroit and other partners to transform a 2.9-acre field into native grassland habitat.

Milliken State Park wetlands along the Detroit RiverWalk (Photo courtesy of Smith Group)

The first step was to pick up and dispose all of the trash, and then remove existing turf grass and pavement. Next, the area was replanted with 39 different kinds of flowers and six varieties of native grasses to become a meadow. Common flowers included partridge pea, prairie coreopsis and native sunflowers. These plants have attracted several insects, such as honeybees, monarch butterflies and swallowtail butterflies. Since the meadow has bloomed, it has become important habitat for birds like American goldfinch, catbird, native sparrows and the ring-necked pheasant, and a great place to bird watch. The meadow has been very well received by local residents and is a strategic move to help reconnect urbanites with nature, bring conservation to the city and help develop a conservation ethic.

Diane Cheklich, member of Detroit Audubon Board of Directors and chair of its Conservation Committee noted:

Callahan Park is our first Detroit Bird City meadow, and it is a wonderful showcase for the concept of urban meadows. Area residents find peace and beauty while connecting with nature there. And Callahan has inspired similar projects, both on City land and on private property as well. This emerging “meadow movement” is critical to help stabilize wildlife populations that are declining due to habitat loss.

Another good example of efforts to create small habitat patches is a pollinator garden. Pollinator gardens are important because pollinators like butterflies, bees and hummingbirds rely on the plants in these gardens for food and habitat. Pollinators help to maintain our ecosystem and pollinate more than 75% of the world’s flowering plants, and nearly 75% of our crops. Without pollinators, wildlife would have fewer nutritious berries and seeds to eat, and we would miss out on many fruits, vegetables and nuts, like blueberries, squash and almonds – not to mention chocolate and coffee, all of which depend on pollinators.

MotorCities National Heritage Area is working with businesses, nonprofit organizations, public entities, neighborhood associations, churches and service clubs to create and maintain pollinator gardens and habitats.

It should be in our own self-interest that we care about having healthy habitats in our communities because, after all, we live in and share the same ecosystem with the plants and animals around us. Opportunities to help create and steward small habitat patches are plentiful in the Metro Detroit area. Examples include:

- Participating in tree planting with Greening of Detroit;

- Building a rain garden or installing a rain barrel with Friends of the Rouge;

- Working with churches to build green infrastructure through National Wildlife Federation’s Sacred Grounds project;

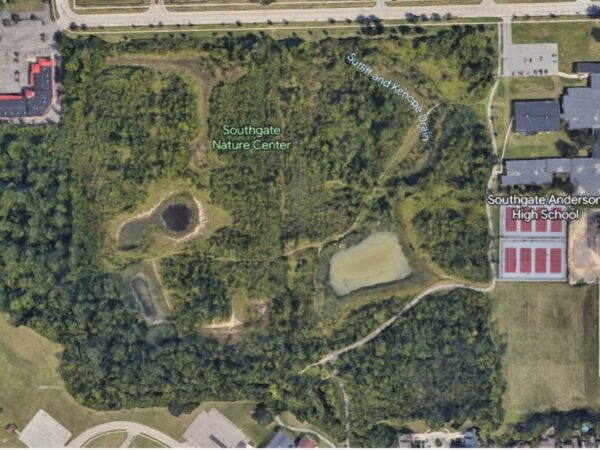

- Creating schoolyard habitats through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat Program;

- Volunteering with the Stewardship Network;

- Joining the Stewardship Crew at Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge; or

- Becoming a stewardship volunteer at Belle Isle State Park; Southeast Michigan Land Conservancy, Six Rivers Land Conservancy or Grosse Ile Nature and Land Conservancy.

Correction: A previous version of this story mispelled Diane Cheklich’s name.

John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. He serves as a Visiting Scholar at the University of Windsor’s Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research and has written numerous books and publications on the environment and the Great Lakes. Hartig also helped create the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, where he worked for 14 years as the refuge manager.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Moment: Lessons from the Ashtabula River cleanup

Featured image: A beaver strolls on the Detroit RiverWalk. (Photo courtesy of the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy)