Ron Meyer and Jerry Gunderson had already spent decades collecting different items when they learned about the trilobites turning up in a quarry just outside Milwaukee in 1984. The two men, friends since childhood, took a trip to the active quarry site and spoke with the foreman about any fossils that might have been found. The foreman directed them to one corner of the site where the shelled trilobite fossils had turned up.

“I pulled up this one rock and exposed this incredible animal,” Meyer recalled. “Beautifully preserved soft tissue—legs, antenna, eyes. Nothing like that had ever been found in the United States before. It was the wildest dream any fossil collector could ever want.”

The men had unexpectedly discovered a Laggerstätte—an exceedingly rare collection of fossils that included the soft tissues of ancient organisms. At the time, there was only one other such site known, the Burgess Shale. While there are several dozen Laggerstätten today, the insights they offer still make them highly valuable to paleontologists. In the case of this site in Waukesha, the fossils showed animals dating back 440 million years ago, to the Silurian Period. At the time, Wisconsin was covered by a warm, shallow sea, populated by corals, worms, sea scorpions, and an assortment of strange creatures.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on these fossils:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Meyer and Gunderson’s discovery was a treasure trove, one they readily shared with research institutions like the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum. Today, nearly three decades since the first fossils were pulled from the quarry, scientists are still uncovering their secrets.

“When we think of fossils, we often think of a giant dinosaur skeleton. In that instance what we’re seeing mostly is the bone and that bone is in part mineralized over time,” said Carrie Eaton, the curator at the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum.

What makes the Waukesha specimens so unique is the appearance of organs: digestive tracts, mouth parts, even tiny hearts. The additional information scientists can glean from such complete fossils offers far more information on how these organisms interacted with their environments.

Try to imagine a cow skeleton on its own, for example. If you’d never seen a cow before, its skeleton would tell you that the animal was a four-legged vertebrate with hooves. But without access to its soft tissues, you’d never know about the four distinct chambers of its stomach, or the size of its ears, or that it has udders.

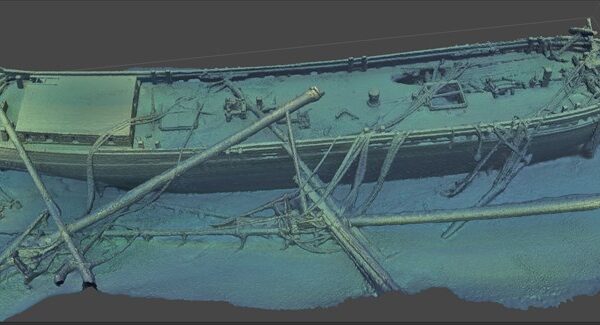

A fossil from the Silurian period on display at the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum. (Great Lakes Now Episode 1029)

Thanks to the Waukesha Laggerstätte, scientists were able to see the full bodies of dozens of organisms, from worms to leeches to trilobites.

In 2020, paleontologist Andrew Wendruff, a professor at Otterbein University, published a paper on the world’s oldest sea scorpion, Parioscorpio venator. The Silurian critter dated back to 437 million years ago and was part of the plethora of species found at the Waukesha quarry. Getting a fuller picture of its body allowed Wendruff and his colleagues to hypothesize that the scorpion may have also ventured out of the water, an important detail about its lifestyle.

More recently, Wendruff and other researchers have hypothesized that the incredible preservation of marine life at Waukesha was due to the abundance of microbial mats in the shallow sea. When animals were trapped in these thick carpets of algae, their corpses were protected from oxygen and the normal decomposition process. This unique setting—surrounded by cyanobacteria—kept the animals intact as they fossilized in limestone over many hundreds of millions of years. Microbial mats can still be found in the Great Lakes today.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on Lake Huron’s microbial mats:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.After the stunning success of their find at the Waukesha quarry, Gunderson and Meyer continued to explore for fossils all around the country. In 2013, the pair uncovered yet another Laggerstätte site, this time in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

The Big Hill Laggerstätte dates to the Ordovician Period, which began around 488 million years ago and directly preceded the Silurian. This part of Michigan was also under a shallow sea at the time, and the area where Meyer and Gunderson found the fossils is thought to have been a lagoon. They uncovered over 100 fossilized jellyfish, as well as over 40 other species. It was another astonishing example of soft tissue preservation from a time on Earth that is exceedingly difficult to study.

Although Gunderson died in January 2021, his impact on the field of paleontology continues on. He had several species named for him, including the Cambrian fossil Raaschichnus gundersoni, and the collections that he helped discover are still being studied by scientists.

“Jerry is probably one of the most interesting people that I’ve ever had the opportunity to know,” Eaton said. “Even as an amateur paleontologist, he made a huge impact into what we know about the paleontology of the Upper Midwest because of his curiosity and perseverance in collecting fossils.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Ancient human remains unearthed at proposed Kohler golf course site in Wisconsin

Ancient stone patterns in Straits of Mackinac add new wrinkle to Line 5 pipeline debate

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: A fossil from the Silurian period found in a Waukesha quarry. (Great Lakes Now Episode 1029)