Collecting data for scientific research across large geographic areas can be challenging, but researchers have found an easy solution – the public.

The Huron River watershed covers 900 square miles, and the Huron River Watershed Council has been collecting data from the watershed for years. Yet collection from such an expansive area would not have been possible without the help of an army of dedicated citizen, or community, scientists.

“Collecting data from throughout the watershed is very time consuming and geographically diverse,” said Jason Frenzel, stewardship coordinator at the HRWC. “Getting decentralized residents to help us do that data collection is very helpful.”

If collecting data from the Huron River watershed is difficult, imagine the difficulty of collecting data from across the Great Lakes region or even across North America. To make data collection quicker and more efficient, scientists often rely on volunteer programs like those at the HRWC to collect valuable data.

These programs allow non-scientists to participate in scientific research through collaboration with experienced researchers. With the help of the public, researchers are able to conduct studies that would be logistically impossible without the help of many volunteers because of time, manpower or geographical constraints.

Dr. Karen Murchie has been conducting research on the native sucker population of lakes Michigan and Superior with the help of volunteer citizen scientists. Those working with Murchie check water levels and count the suckers in 17 locations around the Great Lakes to better understand the behaviors of the sucker, a fish that provides valuable nutrients to the streams it inhabits.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on Murchie’s sucker research here:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Matt Peter, a citizen scientist working with Murchie, told Great Lakes Now in an interview that citizen science programs like Murchie’s provide a unique opportunity for non-scientists to participate in scientific research that has a positive impact on the Great Lakes region.

“It’s an opportunity for people of all ages, regardless of their background, to participate in real research and collect real data,” Peter said. “It doesn’t matter whether you have an institutional knowledge of the scientific process or of science in general, it’s just a great opportunity to get out, collect data for the researchers to use to develop and understand the natural world.”

Citizen science projects vary in difficulty, commitment and subject matter. Some are as easy as taking a photo of wildlife or downloading an app, while others involve precise data collection. Some require training, while others do not. Yet they all provide an opportunity for non-scientists to get involved in the scientific process, learn something new or even have an impact on policy.

Karen Murchie guides volunteers in documenting the sucker spawning run. (Great Lakes Now Episode 1026)

Great Lakes Now compiled a list of citizen science opportunities around the region. Check it out here:

Citizen Science Opportunities: How can you get involved in scientific research?

The name is new, but the concept is not

While the term ‘citizen science’ is relatively new, the idea that non-scientists can contribute to scientific research and make discoveries is not.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, famous historical figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson took detailed weather observations. Jefferson even recruited volunteer weather observers across six states, an idea that eventually became the National Weather Service’s citizen science Cooperative Observer Program.

In the late 1800s, Wells Cooke began collecting data on migratory birds. With the support of the American Ornithologists’ Union and the U.S. government, the Bird Migration and Distribution program collected 6 million bird observations from volunteer citizen scientists until its end in 1970. Beginning in 2009, citizen scientists worked with the United States Geological Survey to convert the data into digital format as part of the North American Bird Phrenology Program.

In recent years, citizen scientists have influenced policy, protected fragile ecosystems and made discoveries. Two planets were recently discovered by citizen scientists participating in the Planet Hunters TESS project, which is hosted on the Zooniverse citizen science platform.

Even before these programs, non-scientists were making and recording observations about the natural world in fields from astronomy to chemistry to physics.

“People don’t recognize that sciences came out of individuals just thinking about things,” Frenzel said. “It wasn’t because there was an institution paying them.”

Huron River Watershed Council’s water focus

As stewardship coordinator at HRWC, Frenzel works to empower citizen scientists to make a positive impact on the Huron River watershed.

“The steward concept is the stewarding of both the natural resource, the river, but also stewarding of the relationships and the progression of our volunteers,” Frenzel said.

The HRWC’s citizen science programs are mostly related to water quality.

A citizen scientist examines water collected during the HRWC’s Winter Stonefly Search. (Photo Credit: John Lloyd via Huron River Watershed Council)

One such program is the River Roundup, which invites citizen scientists into the field to help trained volunteers collect insects and other creatures. The type and number of species gathered provides valuable insight into the health of the river.

The HRWC uses benthic macroinvertebrates, a class of small aquatic animals and insect larvae, as a key indicator of water quality.

“They are exposed to any potential pollution that happens on in the area that they’re at over their life span in the water.” said Frenzel. “They might be exposed to really high water quality or really poor water quality.”

For example, stone flies are generally intolerant of water pollution, while mosquitoes can typically tolerate it. Depending on the number of these and other benthic macroinvertebrates found in the water by citizen scientists, the HRWC can get a general idea of the water quality: high or low, getting better or getting worse.

For those not as interested in creepy crawlies, the HRWC offers Chemistry and Flow Monitoring, where citizen scientists collect data on volumetric flow and chemical parameters. Unlike the general data collected from River Roundups, data gathered from Chemistry and Flow Monitoring is specific, allowing the HRWC to understand what is happening in the water at a particular moment.

“When we start to marry those two sets of data, general and precise, we start to have a much better understanding of the water quality.” Frenzel said. “Both of those programs are multi-year, multi-decade programs. Over time, we started to see changes in the averages within those programs.”

Those changes allow HRWC to track the river’s improvement or decline over a long period of time.

A citizen scientist records data in the field for one of the Huron River Watershed Council’s citizen science programs. (Photo Credit: Huron River Watershed Council)

Community impact

In Detroit, citizen science plays an important role in Community Action to Promote Healthy Environments, a community-based participatory research partnership working to develop and implement a public health action plan to improve air quality and health in Detroit.

Raquel Garcia, executive director of Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision, a CAPHE member, said that having residents participate in air quality monitoring efforts is empowering, particularly because the data collected by residents goes on to make their communities healthier and safer places to be. Garcia hopes that SDEV’s model for citizen involvement will be used as a roadmap for environmental improvements in other communities.

Garcia also sees citizen science as an opportunity to fix systemic problems with scientific research.

“Conservation and the environment has a lot of institutional racism in it.” Garcia said. “It belongs to the scientists; it belongs to the super educated people. I think that’s why we see people opt out of involvement. They don’t believe that their contribution and involvement and engagement matters.”

SDEV is working to make sure residents understand that their work makes a real difference.

“One of our goals is to make sure that residents celebrate their wins. We really want the residents to understand that their participation made it happen,” Garcia said.

Elsewhere, citizen science projects are also often the driving force behind policy changes and public awareness campaigns.

Frenzel said that the HRWC’s citizen science data was used as evidence of a phosphorus loading problem in the Huron River watershed. The city of Ann Arbor later passed an ordinance banning fertilizer with phosphorus, which contributed to a cleaner Huron River. Several years later, Michigan passed a similar law that banned the use of fertilizers with phosphorus unless the landowner demonstrates low levels of phosphorus in the soil.

“Our citizen science data has gone on protect rivers throughout the state.” Frenzel said.

Mark Mattson, the president of Swim Drink Fish Canada and the Lake Ontario Waterkeeper, shared how the water sampling citizen science programs through Swim Drink Fish have provided unprecedented public access to water quality data.

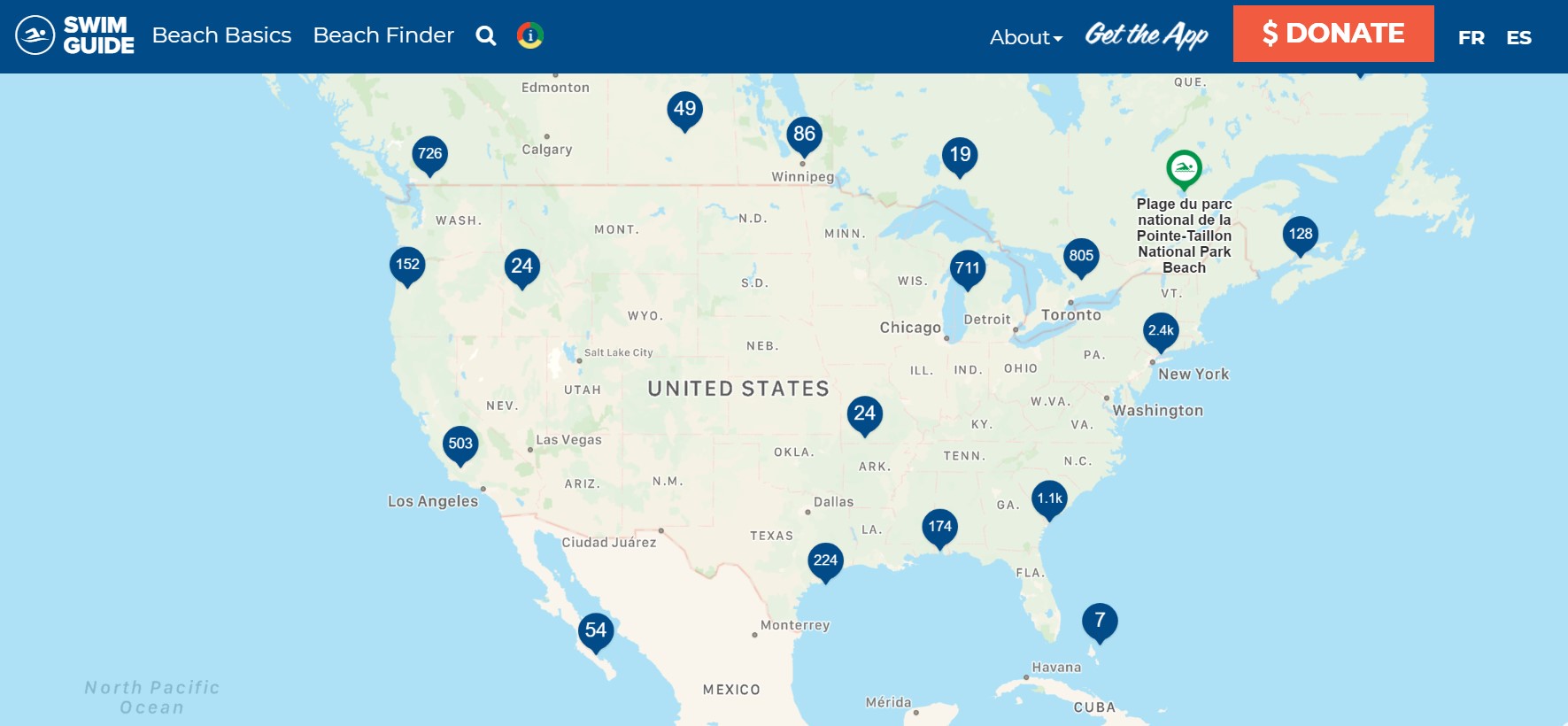

“We created something called the Swim Guide, where we put a pass or fail behind each sample and ultimately share that with the public,” Mattson said.

Swim Guide’s interactive beach map

Now, Swim Guide is used in 11 countries by over 2 million users, collecting samples from over a thousand beaches. Much of that sampling is done by citizen scientists.

“When I started at Waterkeeper, one of the first things I was teaching those who wanted to be part of the movement was this idea that science is possible for the citizens, and not only possible but it’s needed,” Mattson said. “Government doesn’t have enough resources or money to have enough investigators or scientists out there to gather all the big data we need to know where the problems are and understand what to do about them.

Mattson said Swim Guide is in the process of expanding the types of data it collects into areas beyond water quality, like water temperature. It’s all part of an effort to make Swim Guide a more effective resource for scientists and the general public.

“We’re trying to translate that data into meaningful and useful information for the public so that they will want to become part of the citizen science movement.”

Getting involved

For non-scientists seeking to be a part of the solution to the most pressing issues affecting the Great Lakes region, participating in citizen science is a sure way to make a difference. As someone on the front lines of the environmental movement, Garcia sees an urgent need for citizen scientists: the time to get involved is now.

“Climate change is happening and it’s coming. And the time is really short. I mean, it makes me want to cry.”

Garcia says that it doesn’t matter what program aspiring citizen scientists choose to participate in. The important part is getting involved in whatever program works best for each individual or family.

“It doesn’t matter who you join, it doesn’t matter,” Garcia emphasized. “Sometimes there’s a policy that’s statewide and so we need people all over, the suburbs and other cities, to make time.”

Opportunities for youth to become citizen scientists exist as well. Swim Drink Fish offers a Water Rangers program specifically designed for kids, and the HRWC’s activities are accessible for people of all ages.

“Our River Roundups are very family friendly. We’ve got lots of college students that are interested in science, plenty of parents that come out, and we have a lot of retirees that join us,” Frenzel said.

For Mattson, being a citizen scientist comes down to the connections he has made with both the Great Lakes and the people who work to protect them.

“I do it because I love it, I do it because I’m connected to it, I do it because I think I can be effective,” Mattson said. “I do it because it gives meaning to me, to my life and to the people I work with, and I do it because the people that I work with on these issues have meant so much to me and to my career. I couldn’t think of doing anything else.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Second Spike: Great Lakes parks anticipate increased visitation this summer

Researchers seek volunteers to document coastal erosion in Michigan

Citizen Science Opportunities: How can you get involved in scientific research?

I Speak for the Fish: April showers bring vernal pools and baby salamanders

Piping Plovers: Despite new challenges, the birds make their comeback

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: A citizen scientist assists one of HRWC’s trained volunteers in the field. (Photo Credit: Huron River Watershed Council)