I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I was engulfed by sparkling, shimmering silver as if I’d jumped into a giant pile of Christmas tree tinsel.

Each ribbon of sterling was nearly identical but en masse they glittered and gleamed in a thousand shades of silver. Dazzling metallic flashes radiated around me with each twist and turn of their slender bodies.

I was completely immobilized and mesmerized by the splendor.

Being surrounded by the school was a real gift as they usually avoided me. Normally, the schools diverted right, left, up or down to prevent any overly close encounters. And who can blame them when everyone is out to get them.

Fish eat them. Birds eat them. Turtles eat them. Minks eat them. Racoons eat them. They’re pretty much the foundation of the freshwater food pyramid. Which should put them right at the top of everyone’s most-important-Great-Lakes-fish list, right?

My admittedly small and unscientific river-park poll asking, “what’s the most important group of fish in the Great Lakes?” not surprisingly included all the popular sportfish. Walleye, perch, salmon, and trout topped the list with muskie and lake sturgeon also receiving shout outs from their fan club members.

No one mentioned minnows.

Big little fish

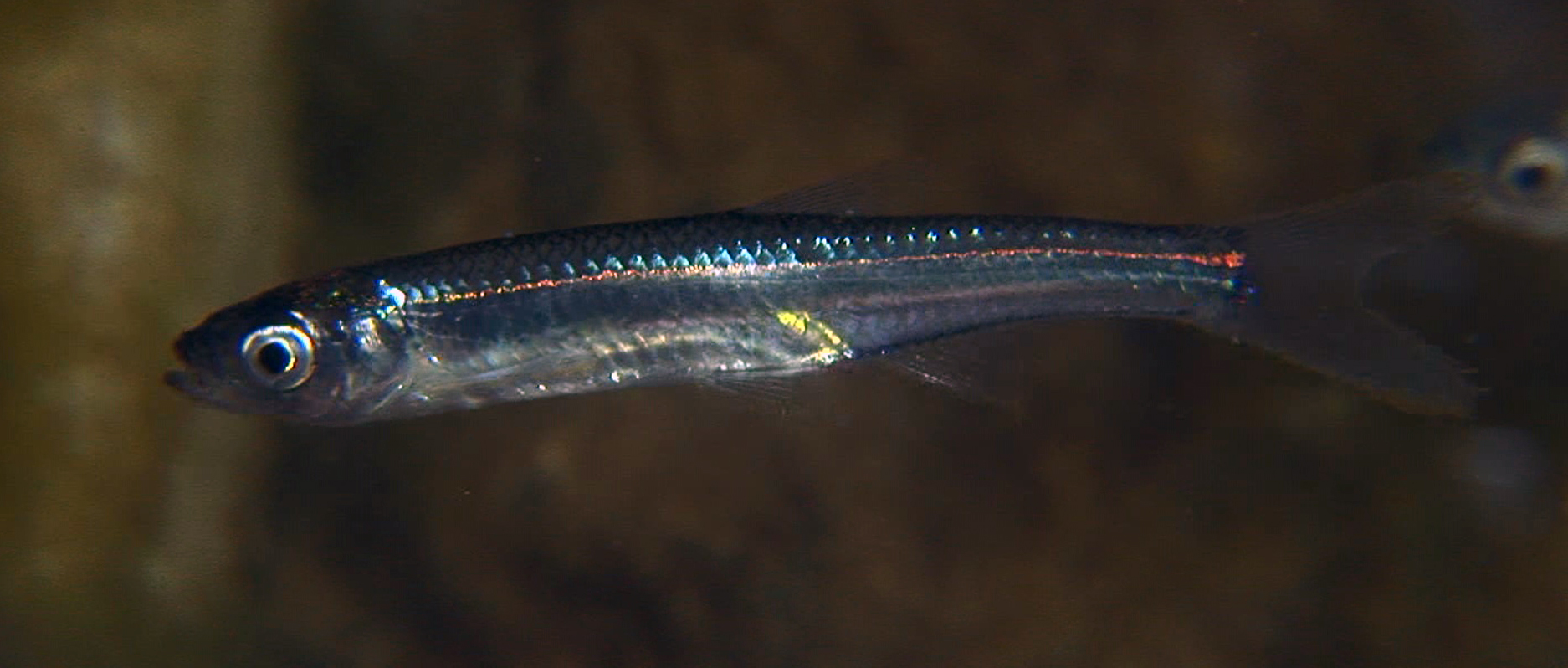

Close-up of an emerald shiner. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Minnow is often used to describe any small fish but as the ROM Field Guide to Ontario Fishes notes, “Not all minnows are small and not all small fishes are minnows.”

The Giant Barb in Thailand reaches 8 feet and 600 pounds while the smallest known minnow Danionella from Burma maxes out at less than half an inch..

Large or small, minnows are strictly freshwater fish; none can tolerate saltwater. With more than 2000 species worldwide, minnows are the largest freshwater fish family and represent about 25% of all freshwater fishes according to the Field Guide to Fishes of Essex County.

Around 231 minnow species are native to North America with about 50 calling the Great Lakes home. Roughly two dozen can be found in lower Lake Huron and Lake Erie with emerald shiners being the most common.

Emerald shiners are the preferred species in the bait fish industry.

Despite physical similarities, minnows vary greatly in their habitat needs and ability to cope with environmental changes. Flathead minnows are often among the first to invade new areas and the last to disappear as an area degrades. While other species are highly intolerant of change and are becoming increasingly threatened.

Spawning behaviors are similarly diverse. Some scatter their eggs. Some build nests. Some use the nest of other fishes.

Moving Targets

With basically everyone targeting them, minnows have had to develop some extra special mechanisms for staying alive.

A series of bones called a Weberian apparatus connects their swim bladder with their inner ear. When their highly-sensitive swim bladder detects movement in the water column it transmits that information to their ears which enables them to ‘hear’ fish approaching.

This apparatus is also found in catfishes and suckers which are close relatives of minnows.

Shiners can also identify and communicate with other members of their species by using their swim bladders to produce sounds similar to whale songs and bird calls.

In addition to sound, minnows are one of the few fishes that use a chemical alarm system. Injured minnows release a pheromone that alerts other minnows of danger. When the alarm is sounded, they squeeze together to try to protect themselves from the threat.

I’ve recently been able to watch this behavior on a big screen from the comfort of my living room and it makes for one heck of a show.

In August, we launched a livestream camera in the St. Clair River. The new Great Lakes Fish Cam is streaming 24/7 on YouTube.

The live stream can be rewound up to 12 hours so viewers can go back and catch anything they missed. Highlight reels featuring the best sightings from each week can also be found on our PolkaDotPerch YouTube channel.

The livestream provides a unique opportunity to observe true natural behaviors. As unobtrusive as we try to be while diving, our presence does affect how fish behave. So, it’s been very cool to see what they do when we are not down there.

You only have to watch one school of shiners streaming past the live camera to understand how important they are to the food chain. At least one but more often three or four large bass are tracking every single school of minnows.

And I’ve counted a dozen including smallmouth and silver bass, walleye and a steelhead all stalking the same massive school of shiners.

I particularly enjoy seeing the predators strike as it’s not something I typically witness while diving. The schools enter my TV from the right side as they travel upstream. Often growing in volume until they fill the entire 50 inches with streaming shimmering silver.

The bass and walleye try to strike without warning. When they attack the school explodes and scatters with the force of a fireworks display. Then almost immediately all the scattered bits of silver flow back together and continue forward like a T-1000 Terminator.

Abundance spawns waste

When you live in a region where you can’t drive more than 30 minutes without seeing a pond, stream, river or lake you are likely to be a larger consumer of water than someone who can drive for days and never see a puddle.

The same applies to fish. If it seems like there is an endless supply, conservation can be a hard sell. And massive schools of shiners exude abundance.

Truckloads of minnows taken from the Great Lakes are delivered to bait shops each week. A significant portion of the bait sold at retail shops in Michigan is harvested from Michigan waters according to Michigan Sea Grant.

Michigan State law requires wholesale catchers to only sell their harvest in Michigan and prohibits minnows harvested here from being exported and sold elsewhere.

The 2016 Michigan Sea Grant article found 25,000 to 38,000 gallons of minnows were being harvested from Michigan’s waters annually. With a wholesale value reaching $1.3 million and a retail value of $5 to $7.5 million, minnows are a lucrative commodity.

These numbers do not include all the minnows wasted in the process. There is loss at the harvest, during transportation, in the store and in bait buckets. Which doesn’t matter cuz they are just a bunch of minnows, right?

Yet every minnow removed from the Great Lakes is essentially taken directly from the mouth of a fish or bird or turtle or other species.

There was a time when lake sturgeons were so abundantly plentiful there was no shame in letting a stack of bodies rot on a dock. And now, we spend millions of dollars each year trying to increase their numbers.

In the face of abundance, it is hard to imagine them going away entirely. But it happens. And not just to other people, in other times and other places.

So, if you enjoy catching walleye or perch for supper. Or you spend hundreds of hours hoping to land a trophy trout or record-breaking muskie. Or if you just like the idea of a healthy Great Lakes ecosystem, then you really ought to be the biggest champion of and advocate for minnows.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Giddy up sucker

I Speak for the Fish: Facing the wrath of a crayfish

Featured image: Looking up at the surface as a school of minnows passes overhead. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)