Great Lakes watchers were pleased that newly elected President Joe Biden’s first phone call to a foreign leader went to Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, hoping the call signals the beginning of more harmonious relations in the basin.

The previous four years under Donald Trump had been rocky. Continuous promises to reduce the funding allocated to the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative left many questioning whether the work of reviving legacy pollution sites or halting the spread of invasive species would end.

“This is a country that can’t agree whether the sun rises in the east, but on the Great Lakes, there’s no debate,” said Marc Gaden, legislative liaison with the Great Lakes Fisheries Commission. “It’s well looked after in terms of funding and policy.”

Bipartisan opposition to Trump’s plan to slash the GLRI budget to $30 million in 2019 was “loud” and “swift,” Gaden said. The plan ultimately fizzled out.

Despite blustery rhetoric about zeroing the GLRI budget, restoration work continued without disruption, Council of the Great Lakes Region president Mark Fisher told Great Lakes Now.

“We’ve seen an even stronger commitment to protecting and restoring the Great Lakes,” he said, including the recent commitment of up to $475 million over the next five years.

Fisher expects this latest funding will encourage the Canadian government to firm up its own commitments to Great Lakes programming, which has been lagging.

“Canada is well behind the United States. There’s a noticeable gap,” he said, between the restoration work undertaken by state and local governments, tribes, and post-secondary institutions in the U.S. and the partnerships that Canada has mobilized. With a federal budget expected in Canada soon, Fisher hopes Ottawa will prioritize Great Lakes protection as part of a larger clean growth initiative.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.The right time for Canada to step up

Canada is already considering what future stewardship in the Great Lakes might look like. In June 2019, a report was presented to Environment and Climate Change Canada proposing $100 million annual investments for the next decade targeting legacy and current environmental challenges. The report from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Collaborative proposed that Ottawa work alongside provincial and municipal governments to safeguard shoreline communities from rising water levels, halt nutrient runoff from agricultural fields, and prevent sewage and other bacteriological pollution from entering the lakes and their tributary rivers. Through the GLRI, America has invested $2 billion in Great Lakes cleanup, the report states. “Now is the right time for Canada to step up and show a similar level of commitment.”

Gaden, whose organization helped spearhead the Collaborative, told Great Lakes Now they spent 18 months consulting stakeholders and formulating a plan for Canadian legislators. “Now we’re pressing members of the House of Commons to fund this initiative,” he said. If Canada does put funding towards the plan, Gaden added, it would be “highly complementary to the U.S. side and what’s going on with the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.”

Debora VanNijnatten, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University who specializes in Great Lakes environmental cooperation, told Great Lakes Now that both countries can approach Great Lakes policy from a shared perspective of tackling climate change.

“It sets a tone to aspire to on the environmental file, and certainly that tone has been absent for the last four years,” she said.

The effect could spur governments into action that, under Trump, were not encouraged, she added.

But VanNijnatten cautions against overselling what Biden and Trudeau will be able to accomplish. Partly this is because the GLRI’s work continued without interruption under Trump. Partly this is because the International Joint Commission continued working “quickly” and “ambitiously” throughout Trump’s tenure. And partly this lack of new action could stem from how localized decision-making is within the basin.

“To a considerable extent, what happens around the Great Lakes depends on what states and provinces are willing to do and fund and put political energy behind,” VanNijnatten said. “That varies around the basin, and it doesn’t change with the [Biden] administration either.”

Ontario’s current right-wing premier, Doug Ford, “is not known to be particularly environmentally ambitious,” she added. “You have to take that into account when you’re thinking about how much [Biden’s election] may mean for new accomplishments.”

Shared concerns across the border

Thinking regionally will also be crucial to addressing long-simmering concerns. Funding to stop the spread of relatively new invasive species like Asian carp must be managed alongside locating $25 million annually to continue controlling sea lamprey. Energy projects like the Line 5 pipeline are a prime example of how infrastructure projects in the basin are seldom the responsibility of a single government, Fisher said.

The ongoing management of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway is another infrastructural concern. Despite worsening congestion at Great Lakes ports, the Seaway is running at 50% capacity. It’s an asset both countries need to utilize more effectively, he noted. Part of this is reaching an agreement on ballast water treatment, a consensus that has eluded both countries for a decade.

“It’s a fully integrated system,” Fisher said. “We need a singular view of how we’re going to protect the Great Lakes as we grow marine commerce.”

In talking about Great Lakes restoration as part of the climate crisis, and in listening to scientists when determining mitigation and adaptation measures to issues like rising water levels, Canada is already looking regionally (and beyond) when it comes to the Great Lakes. According to VanNijnatten, this includes everything from nature-based agricultural solutions to low-carbon energy and green infrastructure.

“This may be an area where Canada could provide some push because there’s been a lot of thinking about green infrastructure here,” she said. “Some of that may wind its way into the work that task forces are doing under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.”

It’s a complicated nexus of challenges that cannot be tackled effectively on their own, VanNijnatten added. Water levels, climate change, infrastructure — these “cooperation clusters” are ripe for bilateral collaboration that tackles them as both a related problem with related solutions.

The good news, she added, is that people working in the Great Lakes are already well versed in protecting the largest freshwater system on Earth. And despite distractions over the last four years, they never stopped working.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

PFAS News Roundup: PFOS in fish, Wisconsin standards in dispute, lacking regulations in Canada

Banned: Canada takes next step toward zero plastic waste by 2030

Canada Water Agency: Government hopes to consolidate water data and management

One key solution to the world’s climate woes? Canada’s natural landscapes

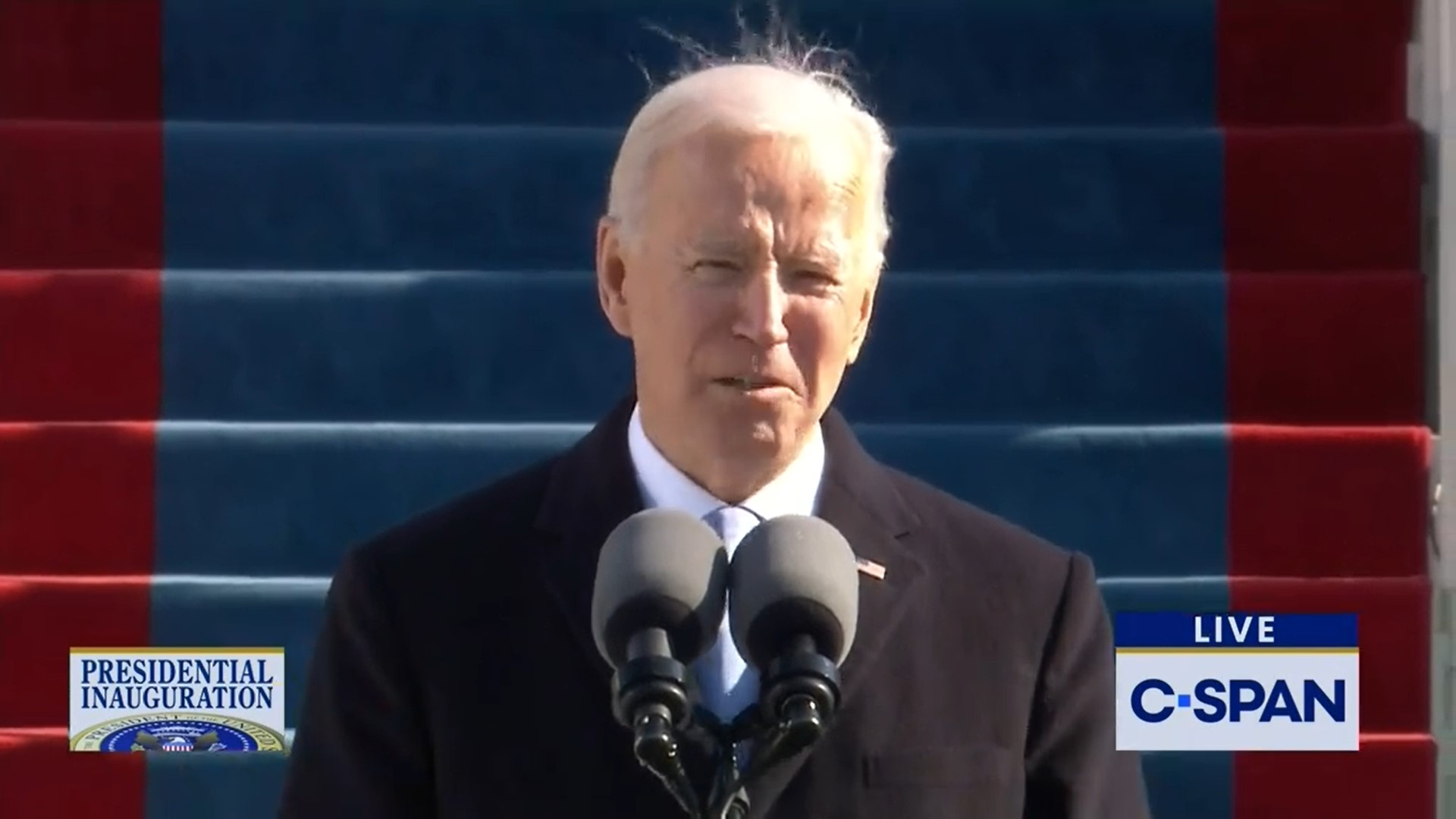

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: President Joe Biden during his inaugural speech on Jan. 20, 2021. (Image from CSPAN)

3 Comments

-

Sadly the Obama Biden administration did not bother to adequately address the problem of ballast water carrying virus and other invasive species that permanently harm our waters causing human, animal, and agricultural damage that can be fatal. This was despite the national academy of science recommendations and bipartisan legislation hr 2830 passing the house of representative 395-7. to address the problem . During Trumps administration a new law (that was completely bipartisan ) was signed allowing the EPA to purposed changing ballast water management practices, in a way that allow ships ballast systems to up take from areas containing sewage, pathogens and toxins without even trying to avoid moving them in to new locations. Amazing in the day and age of covid in sewage and the influence of covid in the aquatic environment being studied.. Sadly with the media staying silent, politicians will never address the issue. So the idea President Biden will now adequately address the problem may be just wishful thinking.

-

With regards to the previous comment:

Arctic ice is melting releasing new virus into the water creating new shipping routes through the Arctic creating warmer waters that exasperate pathogenic problems in water.

Knowing this, It should be noted that before leaving office President Obama by executive order amended executive 13112 (invasive species)with executive order 13751 to consider human health.

(below is an excerpt)

“Of substantial growing concern are invasive species that are or may be vectors, reservoirs, and causative agents of disease, which threaten human, animal, and plant health. The introduction, establishment, and spread of invasive species create the potential for serious public health impacts, especially when considered in the context of changing climate conditions. Climate change influences the establishment, spread, and impacts of invasive species.” Unfortunately it appears the overwhelming bipartisan legislation signed into law in 2018 did not even consider President Obama’s executive order when tasking the EPA to draw up regulations in October 2020. What a slap in the face this is to President Obama’s executive order for change. Perhaps the EPA under the Trump administration felt it would not fit into the narrative they crafted to satisfy the bipartisan legislation signed into law using achievable cost as the standard. -

With regards to the previous comment:

Arctic ice is melting releasing new virus into the water creating new shipping routes through the Arctic creating warmer waters that exasperate pathogenic problems in water.

Knowing this, It should be noted that before leaving office President Obama by executive order amended executive 13112 (invasive species)with executive order 13751 to consider human health.

(below is an excerpt)

“Of substantial growing concern are invasive species that are or may be vectors, reservoirs, and causative agents of disease, which threaten human, animal, and plant health. The introduction, establishment, and spread of invasive species create the potential for serious public health impacts, especially when considered in the context of changing climate conditions. Climate change influences the establishment, spread, and impacts of invasive species.” Unfortunately it appears the overwhelming bipartisan legislation signed into law in 2018 did not even consider President Obama’s executive order when tasking the EPA to draw up regulations in October 2020. What a slap in the face this is to President Obama’s executive order for change. Perhaps the EPA under the Trump administration felt it would not fit into the narrative they crafted to satisfy the bipartisan legislation signed into law using achievable cost as the standard.https://swindonvehiclerecovery.com/