Editor’s Note: This story was updated on April 8, 2020, to add more information on the Ontario government’s new policies.

As COVID-19 continues to spread across the U.S. and globally, threatening the health and economic prospects of many, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has suspended enforcement of broad swathes of its own regulatory policies.

In a widely reported March 26 release, the organization announced an “Enforcement Discretion Policy” under which it “does not expect to seek penalties for noncompliance” regarding a variety of monitoring and emissions reporting.

The EPA also stated that it “does expect operators of public water systems to continue to ensure the safety of our drinking water supplies.”

While the policy is described as temporary in agency releases, the organization has not included a date for enforcement to resume.

Environmental organizations and press outlets responded swiftly with criticism.

Many critics of the policy served previously on the EPA. Gina McCarthy, former head of the EPA under the Obama administration, now President and CEO of the Natural Resources Defense Council, described the order in a March 26 release as an “open license to pollute.”

The Guardian described the policy as “signaling to companies they will not face any sanction for polluting the air or water of Americans.”

Opponents of the easement have also cited recent claims that polluted air can act as a comorbidity with COVID-19, asking for more transparency and stronger safeguards for public health in the midst of a swirling pandemic.

The suspension of enforcement comes just days after a 10-page letter issued by the American Petroleum Institute, an industry lobbying group, citing “limited personnel capacity to manage the full scope of the current regulatory requirements.” The letter goes on to outline a range of obstacles in reporting under pandemic-related conditions and describes the oil industry’s own efforts to combat the spread of COVID-19, requesting that requirements even to file for exemptions be lifted.

“Individual requests for relief would be burdensome to file and track and a more holistic approach may be necessary,” the statement reads, stating “nonetheless, industry will make efforts to comply with requirements, but obviously the situation may limit some activities.”

Companies are not required to announce any pauses in their monitoring publicly. According to an agency letter sent Thursday to Congress, the entities need only document their bases for cessation internally, keeping them on hand should the EPA request them, considering the relation to the pandemic “on a case-by-case basis.”

Read other Great Lakes Now coverage on changing government oversight in the Great Lakes region:

Risk to working class and communities of color

Speaking to Great Lakes Now, NRDC spokesman Josh Mogerman called the new EPA policy a significant break with precedent in terms of its breadth, unclear termination date and early enactment, even in light of a string of deregulatory moves under the Trump administration.

“They essentially said to a lot of polluting entities that they don’t need to collect data and report the data, which in turn means that there’s nothing on which enforcement would be based on,” he said. “In the past, when in the face of disasters, the agency has taken a more relaxed position on things. But it’s always been geographically and time-limited; it’s been in response to something, not sort of proactive, in advance before anyone has started to see disruption.”

Though the EPA’s letter to Congress notes an exception to the suspension, stating a need for organizations to contact them in “cases that may involve acute risks or imminent threats, or failure of pollution control or other equipment that may result in exceedances,” it’s unclear how such risks could be evaluated or anticipated without consistent monitoring.

“This, I think, feels to many like an extension and a much more radical extension of policies that have been moving forward throughout this (presidential) administration,” said Mogerman. “I think that’s part of the reason why there is concern. Because it feels to many as though this is taking advantage of a very difficult situation that we’re all dealing with to advance existing priorities.”

Mogerman expressed particular, immediate concerns for “fenceline” communities, who are already at risk in terms of access to clean air and water around the country, and who often reside in historically industrial areas across the region.

“There’s a lot of similarity in the communities at risk, between the working class and communities of color that are already bearing a disproportionate burden from pollution impacts,” he said. “At a moment where we have a pretty exquisite public health emergency, anything else that we’re doing that drives other public health stressors is problematic. So whether it’s related to (COVID-19) or not, it’s at a point where people are already under health stress.”

New normal or less harmful than it appears?

University of Windsor Professor Mike McKay, Photo University of Windsor

Speaking to the rollback’s immediate effects, Michael McKay, director of the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research at the University of Windsor, said he suspects that the policies may be less harmful than they appear at first glance.

“This is another case where when you hear the news initially you’re shocked,” he said. “And then you read into it in a little more detail and maybe the bark is worse than the bite. The EPA does) state that they’re not changing compliance but they’re providing a little bit more flexibility in light of the pandemic.”

McKay also pointed to the dampening effects of reduced industrial activity, a small environmental upside at least on a broad scale, seen around the world in regions hit by the pandemic.

“We’re seeing about a 25 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, we’re seeing reductions in carbon monoxide emissions from automobiles. So these reductions we’re seeing in activity, which are linked to this slowdown in the economy, again might mitigate to some degree the changes in policy that the EPA is adopting.”

According to McKay, the clearer environmental concerns may lie further down the line, once the economy restarts again.

“The big concern is what happens when we ramp things up again? We may have industry going into overdrive trying to catch up. And will these policies be changed in the same timeframe?” he said. “It’s always a concern when you ease up on things that it becomes the new normal.”

When asked whether broad emissions reductions might dampen the effects of the EPA’s policy suspension, Mogerman acknowledged that was difficult to predict, pointing instead to how environment, public health, industry and equity intersect at the level of individual communities.

“There are a lot of people threatened by this. They know they need to wash their hands, they know that they should be putting on a mask, but they don’t know if there are increased emissions from a refinery nearby or from an industrial facility. It’s difficult to protect yourself in the same way,” he said.

When one of the main instructions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to wash your hands often, anything that could complicate water supplies is a concern, Mogerman added.

“This isn’t just about air pollution, it’s about water pollution. And that includes sewage spills and other things (the EPA monitors) that are not necessarily related to industrial pollution,” he said. “Part of the problem is the potential for increases in that, but the bigger thing is for the public to not be made aware if there is an increased problem so that they can’t protect themselves.”

This loosening of regulations under the Trump administration seems to be gathering steam, including new rollbacks of auto emissions standards this week.

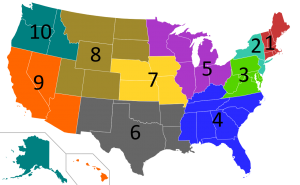

On March 20, the Department of Transportation announced it was issuing a similar stay of enforcement to the EPA’s, but for its pipeline compliance operations under the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. The same organization oversees Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline, which runs through the Great Lakes. The controversial Keystone XL pipeline’s construction is expected to proceed as well.

Keep up with Great Lakes Now’s coverage of Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline:

Farmers in favor of suspension

Representatives in the agricultural industry have praised the EPA’s suspension, as detailed in a recent release from the agency. Zippy Duvall, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, called the move a “common-sense policy that safeguards essential environmental protections.”

“Farmers and ranchers care about the environment and appreciate the importance of complying with government regulations,” he said. “But we all know COVID-19 has presented an unprecedented situation that could disrupt and add significant stress to critical food suppliers and supply chains.”

Scott Yager, chief environmental council for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, said the suspension provides “cattle farmers and ranchers certainty that they will not be subject to overzealous enforcement actions as a result of unavoidable issues brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

But while the suspension frees up industry players to operate more comfortably during an economic downturn, manure and fertilizer runoff remain leading sources of pollution for the Great Lakes, as well as rivers, wells and inland lakes in the region.

They’re just one of a range of industrial concerns that the EPA typically plays a role in monitoring, a process crucial to environmental preservation across the region.

How does farming affect the Great Lakes? Read more on Great Lakes Now:

The role states and provinces can play

While Canada’s federal government has not suspended environmental enforcement laws due to the pandemic as of April 3, McKay reports that the pandemic has stalled or interfered with monitoring in many areas.

Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment is still providing “essential” services, which includes water assessments at municipal intakes, according to McKay. Labs remain open but are to prioritize testing based on whether they’re essential to human health.

“We would typically have springtime monitoring of the Great Lakes by both the U.S. EPA and by Environment and Climate Change Canada,” he said. “That’s not going forward this year. Hopefully things turn around so that we can at least do the monitoring in summer. Here in southwestern Ontario, southeast Michigan, we’ve got concerns about agricultural activity and ensuing harmful algal blooms in western Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair.”

“We would typically have springtime monitoring of the Great Lakes by both the U.S. EPA and by Environment and Climate Change Canada,” he said. “That’s not going forward this year. Hopefully things turn around so that we can at least do the monitoring in summer. Here in southwestern Ontario, southeast Michigan, we’ve got concerns about agricultural activity and ensuing harmful algal blooms in western Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair.”

He called particular attention to the role of states and provinces.

“There are some real concerns about our ability to monitor the pulse of Lake Erie this summer without having the active monitoring and intervention of our state, provincial, federal agencies,” he said.

At those smaller governmental levels, environmental agencies often enforce “more stringent” policies than a federal organization might, creating an opportunity to retain some of the environmental standards put at risk by regulatory rollbacks, according to McKay.

That may be changing, however.

On April 2, Alberta became the first province to issue a stay of enforcement similar to the EPA’s. The move effectively halts all environmental reporting in the province, according to The National Post, making an exception only for drinking-water facilities.

The order may last anywhere from 60 to 90 days, and filings with the agency are only required in the event of an accident or spill.

The Ontario government suspended environmental protection oversight rules this week, citing response times during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The suspension would allow government ministries to push forward projects or laws that could impact the environment without consulting or notifying the public, National Observer reported on April 8.

Reflecting on the lack of transparency required in the EPA policy, Mogerman suggests that could be as grave a threat as any heightened environmental risk.

“We petitioned to at least make folks who are not measuring their pollution any more, who are responding to this (pandemic) and feel that they can’t live up to the requirements to at least say so in writing,” he said. And that’s something that in the past, when you’ve had other sort of smaller-term similar kinds of actions, at minimum, they would have to say ‘Yeah, we can’t do this.’ That’s not being asked of anybody right now, and that’s a big deal.”

Featured Image: FILE – In this July 11, 2018, file photo, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler speaks to EPA staff at EPA Headquarters in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)