This is part one of a series of articles looking at the Upper Peninsula’s energy situation and how it relates to the ongoing Line 5 debate. In this piece, we look at how energy utilities developed in the Upper Peninsula, how this tied into the mining and logging boom of the mid-1800s, and how demographic shifts over decades effect energy rates and distribution today.

Four years after Michigan was formally admitted into the Union in 1837, a mild-mannered geologist from New York, Douglass Houghton, prospected the Keweenaw Peninsula, the “rabbit’s ear” jutting out northeast of the UP, and noted its significant pure copper deposits that touched off a mining boom that lasted until the end of World War I.

“All of the mines were in the central and upper-western part of the peninsula and today there’s only a couple of operating mines,” said Daniel Truckey, director of the Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center at Northern Michigan University.

Naturally, a sudden industrial boom needed a sizeable labor force, with immigrants largely coming from Italy, Finland, Cornwall and Scandinavia. Concomitant with mining, logging became a significant industry in and of itself, not only for the construction of homes but for the mineshafts.

“There’s a joke that most of the UP’s early forests are all underground,” Truckey said.

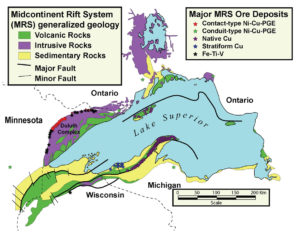

During this heyday, a majority of the UP’s population lived in the west and central-west counties of Houghton, Keweenaw and Ontonagon, where the peninsula’s copper and silver deposits rested. Iron mining was situated mainly in Gogebic and Iron County, which lay along the border of Wisconsin.

“What you had was people’s homes were actually very close to the mining operations,” Truckey said.

“In fact, the way that a lot of towns were broken up was by what they called ‘locations,’ so within each town there might be several locations and they were all connected to a specific mine operation. A town like Calumet might have half a dozen different mining operations all owned by the same company, different shafts and components of the mine, and then each of them would have a location where miners could work and live.”

Given that most ore deposits lay close to either Lake Superior or Lake Michigan, and mines and mining towns developed amount main riverways, hydroelectricity became the primary method of power generation and distribution. Further industrialization coincided with further electrification of the UP, a rarity for a region so sparsely populated and away from major metropolises.

Here the Upper Peninsula Power Company emerged. UPPCO is an electrical utility that serves a majority of the UP both territorially and by customer base, born when the Houghton Electric Light Company entered into a merger with the Iron Range Light and Power Company and the Copper District Power Company.

Here the Upper Peninsula Power Company emerged. UPPCO is an electrical utility that serves a majority of the UP both territorially and by customer base, born when the Houghton Electric Light Company entered into a merger with the Iron Range Light and Power Company and the Copper District Power Company.

The conclusion of World War I marked the beginning of the end of the mining craze. Even then, years before, there was already a significant exodus of workers out of the UP and towards larger urban centers like Detroit and Chicago as the auto industry rapidly expanded. Unionization and strikes steadily grew in this period as well, making employment more expensive for mine operators and driving miners away from the industry and toward better pay elsewhere.

Cities like Calumet, Truckey pointed out, used to be the largest urban centers of the UP. Now it holds a population hovering around just 700.

In the decades that followed, the Upper Peninsula’s population distribution morphed into a trend that has lasted up to the present. The majority of residents now live either in major cities such as Marquette, Sault Ste. Marie and Escanaba or along the main roads.

Most roads thus formed to connect the various communities of the UP, aided by a highway system that was first built up in the 1920s and expanded further under President Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway Program of 1953. Coincidentally, the beginning of Eisenhower’s program was the same year that saw the completion of the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline, built as the most efficient method to transport Canadian oil from Alberta to Sarnia, Ontario, through Michigan.

Imperial Leduc No. 1 oil well, Leduc, Alberta, Photo by Provincial Archives of Alberta via flickr.com Public Domain

In much the same way that the mining boom attracted industry and peoples to a remote part of Michigan, a fortuitous discovery of oil at the Leduc No. 1 drilling site near Edmonton, Alberta, in 1947 sparked a crude oil boom that touched off major industrialization and settlement in Calgary and Edmonton.

Prior to this, Canada had been largely dependent on the United States for its crude oil needs. Imperial Oil formed in 1880 from the merger of 16 production and refining companies as a means of staving off competition from American competitors, but by 1899 it became an affiliate of American oil magnate John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

In 1949, Imperial Oil successfully requested the incorporation of the Interprovincial Line Company from the Canadian government, which would oversee the distribution of western Canada’s oil reserves throughout Canada and eventually into North American markets.

The discovery of oil at Leduc and later at the Redwater site gave rise to the Enbridge energy distribution company, as the refinery in Edmonton simply couldn’t process all the crude oil that spewed forth. Pipelines began sprouting outward, the first one completed in 1950 and distributing oil to Superior, Wisconsin.

The minister of trade at the time, C. D. Howe, initially wanted to keep an all-Canadian route to transport oil to Sarnia, Canada’s largest petrochemical and refinement center. When it was noted that doing so would delay construction by another year and incur an additional $10 million cost (roughly $95 million in today’s currency), Howe accepted the Interprovincial Line Company’s plan to extend the pipeline from Superior, Wisconsin, through the Upper Peninsula, under the Straits of Mackinac and down through the Lower Peninsula to reach Sarnia, across the river from Port Huron.

That became what we now know today as Line 5.

IPL’s fortunes continued to improve beyond the 1950s. The OPEC oil crisis of the 1970s, combined with the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1978, led to a surge in the price of crude oil and higher demand, spurring on pipeline expansion and extensions. The company changed its name to Enbridge in 1998.

As the 20th century wore on, homes turned more and more towards coal and propane to heat themselves, as electricity generated by hydroelectricity became exponentially more expensive over the years. While propane became the most efficient for smaller, isolated housing units, most cities and electrical utilities relied on coal plants for their power.

While the primary function of Enbridge’s Line 5 was to transport Canadian crude to Ontario via the most efficient route possible, a side effect is that today it provides around 60% of the Upper Peninsula’s propane needs, though little to none of its natural gas demand. Roughly 18% of all Upper Peninsula households or around 22,600 homes heat with propane, based on a report by Richelle Winkler, an associate professor of sociology and demography at Northern Michigan University, for Governor Whitmer’s UP Energy Task Force.

The Presque Isle Power Plant presents a microcosm of the UP’s former dependence on coal. Its eventual closure also signaled the shift towards natural gas and other energy production methods.

First constructed in 1955 at the northernmost tip of Marquette, the plant was jointly run by UPPCO and Cliffs Electric Service Company and continued to add new units, starting with Unit 2 in 1962 and building more until 1979.

Presque Isle became the main provider of energy for the Marquette region even as four of the nine units were decommissioned between 2007 and 2009 by We Energies, a Wisconsin-based utility that bought the plant in 1988. On March 31, We Energies fully shut down the plant to be replaced by two new natural gas facilities in the cities of Baraga and Negaunee, managed by Upper Michigan Energy Resources, a subsidiary of We Energies.

The move to switch to natural gas came as a cost reduction measure, a way to meet lower emissions standards and still provide energy to UP residents despite the large geography and small population.

Featured Image: Loading copper onto a steamer (SS Juniata) in Houghton, Michigan, Photo by Detroit Publishing Co. via wikimedia.org

Read more stories from the Upper Peninsula’s energy situation series