For Madison’s Jane Elder, the timing was optimal when she launched a career in environmental activism. She was coming of age and interested in the environment in the early 1970s. At the same time, interest in the environment was “blossoming” as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established and the Clean Water Act became federal law.

What followed for Elder was a multi-decade career in the trenches of environmental activism, highlighted by her tenure at the helm of the Sierra Club’s Great Lakes program. In 2019, Elder was awarded distinguished alumni status by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies.

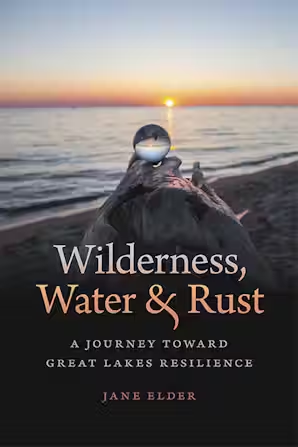

Great Lakes Now recently spoke with Elder on the release of her new book, Wilderness, Water & Rust: A Journey Toward Great Lakes Resilience.

Elder explains why her personal and professional lives intertwined, the history and impact behind the boom-and-bust cycles in the Great Lakes region, and advice for emerging activists who want to follow an environmental policy career track.

The interview was recorded, transcribed and edited for length and clarity.

Great Lakes Now: The book is part personal memoir combined with a chronicle of your decades-long work as a policy advocate to protect the Great Lakes. Why was it important to include both?

Jane Elder: The personal and the policy are so intertwined. Without my childhood experiences and the way I was raised, I doubt that I would have become an activist.

My mother was born near the shores of Lake Superior and we’d make trips there and I saw how much she loved Lake Superior and the Great Lakes, so the threads were there.

The environmental movement was blossoming about the time I entered college. I cared about the environment and wanted to be in that space. I wove them together, in part, because there are personal stories behind all the policy that’s made. We tend to think, Congress passed a bill or the EPA made a decision. These decisions don’t happen in a vacuum. They are part of long, complicated processes with personalities and people with various pressures on them.

I wanted to shed light on the policy process for people who don’t engage in or understand it. I also wanted to document some of the history of this era in the Great Lakes region. As we head toward more severe climate and other environmental threats, it’s important to understand where we came from, how we got there, where we got stuck and what we might do in the future. I wanted to share lessons learned.

(Book cover design by Erin Kirk via Michigan State University Press)

GLN: In the prologue, you set the stage for what follows by describing the boom and bust cycles of the auto industry beginning with the 1950’s and later as you came of age raised near Flint. By the 1980’s the Great Lakes region had been tagged the “Rust Belt” and by 2014 disinvestment in Flint contributed to the tragic water crisis. Why start a Great Lakes book from that perspective?

JE: That’s where I started. I was born in Flint at McLaren Hospital in 1954 eight days after General Motors produced its 15 millionth car. There was a huge parade attended by 100,000 people. I was born into the generation of post-World War II optimism where technology could save us and good Americans had good jobs and the union would protect you and what was good for GM was good for the country. All that was part of the fabric and patriotism that we learned.

Then we began to watch it crumble and see the toll it takes on people and I realized that the story of Flint as a boom-and-bust town was really the story of the region in different ways. It was similar to a copper mining town and there has been this 400 year history of extracting the capital, taking and using it up, leaving the environment, community and the workers behind. That’s a model that’s not sustainable or healthy for people and the environment. Flint’s story is very much a story magnified in different communities in different ways across the region.

The tragedy of what happened with Flint’s water is an example of what happens when you strip a community of so much of its capital, its community cohesion and you disempower the residents who are still there. I wanted to tell part of the story of Flint because I saw both its promise and its tragedy.

GLN: An internet search for “Great Lakes” and “Rust Belt” quickly reveals a number of current references in spite of efforts to rebrand the region. For example, former Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett campaigned to call it the “Fresh Coast.” Is the “Rust Belt” moniker a fair description in 2024?

JE: It is for some parts of the region. I know we have come a long way, but there are still communities that are largely left to their own devices. Michigan’s John Austin (Brookings Fellow) talks about some of the communities that are really struggling to find renovation, resilience and regeneration.

I recently spent an afternoon as a tourist in Detroit, where it was exciting to see new apartment buildings downtown, vibrant restaurants, and people on the riverwalk. You can see the reinvestment beginning to blossom and that the work is paying off.

But facing south from my hotel, I had a view of Downriver toward industrial Zug Island where we’re still dealing with that rugged, dirty technology and pumping stuff into the atmosphere. So, it’s the tale of two stories coming from these communities. To brand the entire Great Lakes region as the Rust Built isn’t fair, but we still haven’t addressed what got us that label and how do we help them revitalize.

GLN: You point out in the book that 30 years after legislation to protect aquatic ecosystems from mercury, safe fish guides are still published in every Great Lakes state. They list the fish that are safe to eat, those that are not and how much. And you cite a study that says only half of the Great Lakes public is aware of the advisories. Have we simply accepted the consumption advisories as the norm? Have we given up?

JE: I haven’t accepted them, but there has been a normalization of degradation that the waters are contaminated, and it worries me that we are not still trying to get to the root of why we have so much mercury in our environment in the first place. Why do we still have PCBs when they were banned so long ago. Why didn’t we have a smarter strategy like prevention and precaution for PFAS?

I worry that the fish advisories and contamination are seen as the way it is in the Great Lakes. That’s a sad benchmark. Why shouldn’t we still be struggling to make sure that there will be a day without fish advisories.

GLN: The book contains a considerable section on the nuclear power plants near the Great Lakes and the health and safety concerns advocates like the legendary Lee Botts had about them. The Palisades plant that borders Lake Michigan was shut down in 2022 after operating for 50 years. Now, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, with support from the federal Department of Energy (DOE), is on the cusp of restarting it in order to meet climate change goals. The DOE is led by former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm. You say, “skepticism about the role of nuclear power in our future is healthy.” Can you elaborate?

JE: Some people see nuclear power as a panacea for clean energy but there are a lot of things about the nuclear power cycle that aren’t clean at all. Starting with the mining of uranium and radioactive source material, its transportation, enrichment, then the long-term question: what do you do with it when you’re done with it?

We still don’t have in the U.S. or Canada any practical long term storage plan for radioactive waste. By default, the aging nuclear plants on the shores of the Great Lakes have become de facto radioactive waste storage sites.

I’m concerned about reupping a place like Palisades because of the costs involved and taking an aging facility and bringing it into another generation. And, we still haven’t answered the question about storage of the spent waste.

GLN: You spent decades immersed in environmental policy advocacy work where progress, if any, may come in small increments after many years. What is your advice to emerging activists who want to follow the policy career track?

JE: The policy and political world now is so different now than it was when I was a young activist.

If we now want to change policy, we first have to work toward getting our democracy functional again. It’s hard and gritty work, but we haven’t passed anything in Congress for the environment in decades. In part, because of the partisan splits, and if we can’t use the basic structures of government to change policy, what’s left to us?

A lot of people like the satisfaction of local and small projects and incrementalism, but climate change and the extinction crisis are driving deadlines that don’t care about incremental approaches. I’m urging young people I know to look at levers for system change because we need systemic scale change if we’re going to turn around any of the current trends. And that’s daunting for people who may have never had a legislative victory to talk about.

We need people with imagination who can engage and say if a system isn’t working, why? Where are the levers within our capacity and skill sets that we can begin to shift the system toward what would be more functional, sustainable, humane, equitable and just. I see that in many younger folks who are looking across the board to make the environment cleaner, but also how do we make our communities more vibrant and equitable. How do we deal with all these complex things that are making life in the modern world so challenging?

GLN: Final thoughts? Something important for Great Lakes residents to know that we haven’t addressed?

JE: While there are many people working on Great Lakes issues, no one is in charge of the long-term plan for the Great Lakes for climate change. I find that staggering.

Beyond that, be curious and ask questions. Why is it like this and who is responsible? Don’t assume that just because there’s a state agency or the USEPA that someone is actually taking care of the Great Lakes at the level that is needed. Good things are happening but a lot of things are falling through the cracks. Ask, who’s in charge? What can I do?

For more information about Wilderness, Water & Rust go to Michigan State University Press.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Michigan author reflects on 20th anniversary of landmark book The Living Great Lakes

Featured image: Jane Elder. (Photo Credit: Bill Davis)