Just like serious birders and all manner of naturalists, many divers keep a life list of the species they have seen. Typically, the more elusive the species, the more coveted the sighting. Size also plays a role in desirability, whether it’s a condor or a blue whale.

When it comes to impressively large and elusive freshwater species, a couple come to mind.

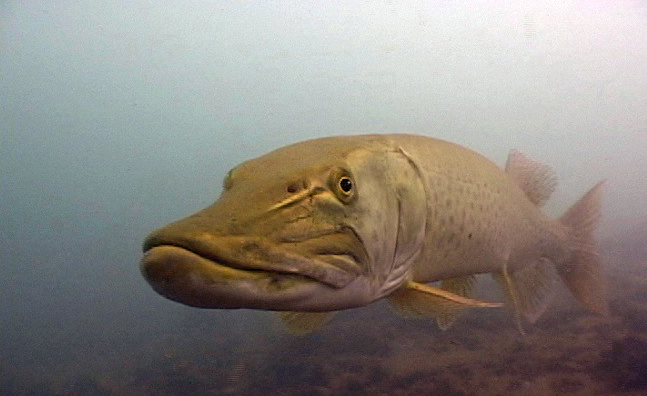

But the one that took me a decade to check off my life list, the one I made hundreds of dives before seeing, the one that others on the same dive have spotted while I missed, would be the enigmatic muskellunge.

Fortunately, muskellunge – or muskies – are far more common today than when I began diving. Today, the majority of our dives in the St. Clair River now include a muskie sighting thanks to the world-class muskie fishery in Lake St. Clair.

Lake St. Clair has the ideal conditions for muskies with a maximum depth of 21 feet and an average depth of just 11 feet. In the summer, this shallow lake gets so warm that cold-water species like whitefish could never survive, but muskies can tolerate water temperatures from near-freezing all the way up to 90 degrees.

Lake St. Clair also contains the largest freshwater delta in the world. The St. Clair Delta is a thriving wetland ecosystem with acres of dense aquatic grasses that provide nursery habitat for fish, shelter for turtles and frogs, nesting sites for birds, and nirvana for a shallow-water predator like the muskie.

An average adult muskie is 3 feet long and about 40 pounds. A record-setting 58-inch muskie weighing roughly 65 pounds was caught in Georgian Bay at the top of Lake Huron in 1988. The world record stands at 72 inches and 70 pounds, according to both the Royal Ontario Museum’s Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario as well as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

A muskie’s sleek torpedo-like form has natural camo-coloring with dark dots and squiggly markings over a beige or light olive body. They have an off-white belly and reddish fins rimmed with gold. In the mottled sunlight that streams into the shallow rice beds which are one of their preferred habitats, a muskie becomes nearly invisible.

Muskies are undeniably intimidating with a wide, gaping mouth overflowing with large razor-sharp teeth. They even have teeth on their tongues and the roofs of their mouths. As apex predators, adult muskies occupy the very top tier of the Great Lakes food chain.

They mostly hunt small- to mid-sized fish, but large muskies will not hesitate to take anything they can catch, from waterfowl and reptiles to semi-aquatic mammals like muskrats.

Muskies are considered ambush predators. They typically lie in wait near grass beds often in only a few feet of water. Like a cheetah stalking prey on the savanna, a muskie will patiently and motionlessly wait for a school of yellow perch to meander by or a mallard duckling to stray too far from its parents. Then with a stunning burst of speed, the muskie pounces.

When diving, I usually feel a muskie before I see it.

I’ll get that oddly disturbing sensation of being watched, an overwhelming and uncontrollable urge to check my hindquarter. When I get that feeling underwater, I know a muskie is probably nearby.

But you only see a muskie if the muskie lets you. And you’re paying attention.

Thankfully, muskies are fairly curious and somewhat territorial, so they occasionally grace divers with a cruise-by viewing. On two memorable dives, one stopped right beside me. I find it oddly appealing the way their noses are flattened kind of like a duck’s bill.

I’d love to spend a whole dive with a muskie, but sadly they seldom stick around for long. On rare instances one might shadow a diver for a hot minute, but more often than not muskies appear and disappear in about the same time it takes for a traffic light to switch from yellow to red.

Muskies can be equally elusive for fishermen as they are commonly known as the fish of a thousand casts.

Lake St. Clair has an active fleet of charter boats that service the muskie fishery. Unfortunately, not all fishermen are fans of the predator. Sportsmen targeting bass, perch, walleye or basically any other fish are typically not fans of muskies.

In some fishing circles, the belief is that muskies scare away other fish, or at least keep them from biting. But, even if they do, muskies are a native species hunting for survival. In my mind, that tops any kind of sport activity.

I can also empathize with the muskie as fishermen often accuse divers of similarly disrupting the fishing. Perhaps we do but, given the number of fish I’ve seen fishermen catch right after I have gotten out of the water after diving, I can guarantee any impact we make is strictly temporary.

In addition to there being far more muskies in the system now than 20 years ago, a reason I see more when diving now is because I’ve learned where to look. When the hair on the back of my neck stiffens, I immediately stare out into the edge of nothingness and wait.

Muskies like to hang right on the edge of the visibility.

Divers commonly refer to the distance from themselves to where everything fades into a dense grey fog as the viz or visibility. The viz at any given dive site can change in a matter of hours depending on any number of factors from wind and rain to boat wake.

Whether the edge of viz is 3 feet away or 20, if I keep watching and I’m lucky, a muskie will magically materialize out of the river fog. I can attest to the fact that the brief encounters are easy to miss.

Seeing a muskie is one thing. Filming a muskie is another matter entirely.

With an encounter time of less than 20 seconds, the camera not only needs to be setup and running, but a good autofocus is essential. Muskies are perfectly designed to blend in underwater. With their preference for hanging on the edge of nothingness, filming them is perversely challenging for both the camera and shooter.

I’m glad they are curious, else I’d never see them at all. It’s just a shame that they don’t find me nearly as interesting as I find them.

It makes no difference that I have already checked muskellunge off my life list. Every sighting is a thrill, and every dive that includes a muskie visit is a gift.

This column was inspired by reader suggestion. If there is a species, you’d like me to showcase please leave a comment below or email Great Lakes Now at nblakely@dptv.org.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Center stage alongside Great Lakes steelhead trout

Sturgeon Restoration: Drawing in the public with a festival

Featured image: The muskellunge, otherwise affectionately known as the muskie (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)