Fatbergs — massive buildups of wipes and hygiene products congealed with greases and oils — make for a cringe-worthy topic. And the damage they cause to sewer systems can be a huge amount of trouble for the people in charge of those sewer systems.

That includes Candice Miller, the Public Works Commissioner in southeast Michigan’s Macomb County. A giant fatberg there cost the county upwards of $50,000 in removal costs in 2018.

Fatbergs have appeared in England and Australia (where they’re called “ragbergs”) and all around the U.S. and Canada.

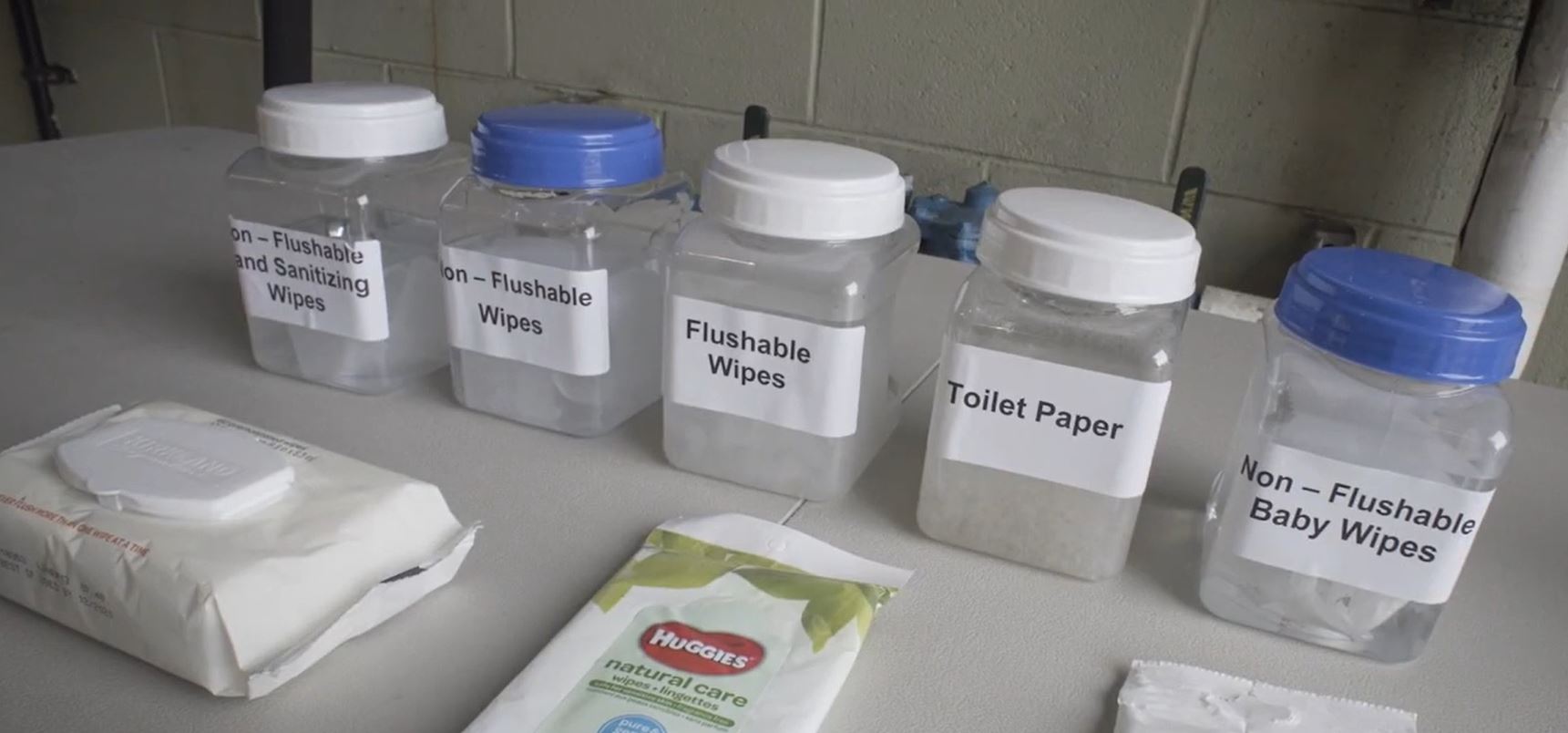

One of the main ingredients for these fatbergs is wipes—both flushable and non-flushable.

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Their prevalence, in part, prompted Miller to file a suit in Macomb County Circuit Court in early May against nine different manufacturers of so-called flushable wipes. Her suit alleges that wipes that aren’t labelled “flushable” do not disperse in water quickly enough to be considered septic-safe or flushable.

“That’s all I’m trying to do here,” Miller said in the YouTube video announcing the lawsuit. “Change the packaging.”

Out of the defendants—Dude Products, Inc., Nehemiah Manufacturing Company LLC, Kimberly-Clark Corporation, The Proctor & Gamble Company, Nice-Pak Products, Inc., Rockline Industries, Inc., Yezis LLC, S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. and C.B. Fleet Company, Inc. — only two responded to Great Lakes Now’s attempts to contact them about the suit.

An email statement from Kimberly-Clark said the company “is fully confident that its flushable wipes break down after flushing and are fully compatible with properly maintained sewer and septic systems.”

Proctor & Gamble sent a slightly longer email statement that “denies the allegations by plaintiffs and stands behind the performance of Charmin Flushable Wipes” and pointing out that the company has removed “septic safe” and “safe for sewer & septic systems” from its wipes labels.

The issue is “too many wipes being flushed that should not be flushed,” according to Dave Rousse, president of INDA, the association of the nonwoven fabrics industry. He said the problem is not flushable wipes, but non-flushable ones that are getting flushed anyway.

Depends on the test

In the U.S., for wipes that have passed tests to be considered “flushable,” those tests were developed by the wipes industry. In two separate research labs, flushable wipes didn’t fare quite so well.

At Wayne State University’s Integrative Biosciences Center, where part of the Macomb County fatberg is being studied, they soaked and sloshed wipes for 48 hours and the wipes didn’t break down much.

At Ryerson University’s Ryerson Flushability Lab in Toronto, researchers created a setup that mimics a typical household drain line. They tested 101 wipes and other products—some labeled “flushable” and some not—using the standard developed by the International Water Services Flushability Group.

A disposable wipe, still intact after being tested for flushability. (Photo courtesy of Ryerson University)

“Not a single product actually passed the test,” said Anum Khan, the graduate student who conducted much of the research.

Some of the products labeled “flushable” disintegrated more than the other products, but still not enough to pass the test, according to Associate Professor Darko Joksimovic, who supervised the research.

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Stuck Bills

It’s a concern that becomes increasingly urgent as wipes become an increasing problem.

With COVID-19 and an increase in wipes purchase and use, there has been a 400 percent increase in wipes found in the sewer system, according to Miller.

But as that fight makes its way slowly through court, members of the House and Senate have tried and are trying to pass bills to make these companies more accountable for the wipes.

In the Great Lakes region, several state legislatures have considered bills related to the language on the wipes’ packages. None of the measures have been enacted.

In Michigan in August 2018, House Bill 6279 was introduced to prohibit the sale of non-flushable wipes without do not flush labeling. It did not make it far. The bill was reintroduced May 20 this year as House Bill 5796 and referred to the Committee on Natural Resources and Outdoor Recreation. No other action has been taken.

In Minnesota, House Bill 2842, which would require wipes that are not flushable or sewer-safe to be labeled with “do not flush,” was introduced in March 2016 but died in committee.

In New York, Senate Bill 5307A was introduced to prohibit manufacturers from labeling wipes as flushable without prior approval. The bill was introduced in January 2016 and has been stuck in committee. Versions of the bill have been attempted in 2018 and 2020 as well with no success yet.

Federal stall

In early February, the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act of 2020 was introduced in both the House (5845) and Senate (3263).

Rep. Alan Lowenthal

Rep. Alan Lowenthal, D-Calif., and Sen. Tom Udall, D-N.M., co-authored the bill.

In the process of developing the bill, the senators had numerous conversations with “advocates out there: the chemicals industry, the plastic industry, people dealing with waste products, community-based organizations” to come up with a draft legislation that was comprehensive rather than piecemeal, Lowenthal said.

“Something as important as this, it’s a comprehensive approach and it changes the focus from the consumer and municipalities, which up until now have been responsible for recycling and purchasing bins and developing community ways of dealing with it,” he said.

The bill, despite largely being about plastic products, does have a section addressing wipes and labeling requirements.

“Along the way, as we began to do it, even though the focus was on plastic pollution, we began to hear from sanitation districts,” Lowenthal said. “They began to educate us. They said, ‘While you’re doing this on plastics, why don’t you hear our stories? We’re finding these wet wipes and other similar products, there’s no regulation to them. They label these as flushable or sewer, septic-safe but in reality these are not safe. There’s tremendous congestion.’”

The people Lowenthal talked to pointed out that some of these wipes are made of plastic fibers which contribute to microplastic pollution.

“So we decided that it would become part of our bill, we would work with them,” Lowenthal said.

The House version of the bill has 70 co-sponsors, and Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich., is one of them.

“What drew my attention to it was primarily, when I was in legislature the production of plastic was something discussed, the production of waste, so the spirit of why they included that is probably to stop pollution because it’s impacting so many people’s public health and environment,” Tlaib said.

While the House bill is continuing to pick up sponsors, the Senate version of the bill has 8 co-sponsors, all from February.

“I think it’s the nature of the beast,” said Rep. Mike Quigley, D-Ill., one of the House co-sponsors. “The jokes of the Senate being where good legislation goes to die, the Senate not being as active a body, the Senate being more conservative, more Republican. But I still have faith. It just takes longer to move them along. So obviously we need a majority of votes over there, but this is a process, this is an extraordinary problem that needs a comprehensive plan, so it sometimes takes a while to get everybody on board.”

With COVID-19 and more attention on systemic racism and police brutality, congressional priority has shifted, but that isn’t necessarily the end of this bill, according to Lowenthal.

“Our expectation is we keep building momentum, and the bill will be reintroduced in early 2021,” Lowenthal said.

Read more about wipes and fatbergs on Great Lakes Now:

COVID-19 Caution: Water Resources Commissioner asks people not to flush cleaning products

Epidemic of wipes and masks plagues sewers, storm drains

Fatberg Quiz: Which fatberg are you most like?

Featured image: Researchers are testing how well various hygiene products break down in sewers — or whether they become fatbergs. (Photo by Great Lakes Now)