Ideology divides opponents on Great Lakes funding

Occasionally a Great Lakes issue garners the public’s sustained attention.

A nerve is hit that moves the issue beyond the focus of the advocates and policy wonks and into the public spotlight. It catches the eye of the mainstream media that only peripherally covers the Great Lakes.

The revelation in 2009 that Asian carp were on the doorsteps of Lake Michigan was such an issue. The 2014 algae-fueled Toledo water crisis that left 500,000 people without safe drinking water for three days was another.

Donald Trump at Hershey PA Victory Tour , courtesy of Michael Vadon

Now comes President Trump’s proposed budget that would eliminate all $300 million in federal funding for Great Lakes restoration.

Trump’s whack to the Great Lakes budget has been in the news for months and interest in it shows no signs of abating.

Specifically, that money is for a program titled the Great Restoration Initiative – GLRI as it’s commonly called by advocates and insiders.

But what is GLRI? What is its genesis? How has it performed in its seven-year existence?

2002

Flashback to 2002.

George W. Bush was not yet at the mid-point of his first term as president and Barack Obama was an Illinois state senator known mostly for his odd name.

But quietly in the corridors of Chicago and Ann Arbor, Great Lakes advocates were planning: planning to launch an initiative to convince the federal government that the neglected problems of the Great Lakes were really national problems and the feds should pony up money – in the billions – to restore the lakes.

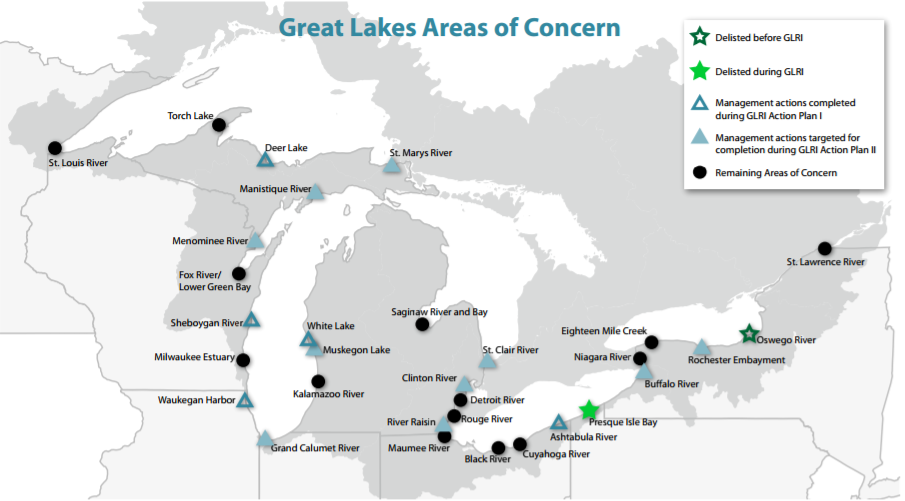

The advocates started slow pitching small-bore legislation that would begin the clean up of the toxic legacy sites left from the industrial era. They were declared Areas of Concern in 1987 and had languished ever since for lack of funding.

And the advocates quickly had their first success.

The Great Lakes Legacy Act became law in 2002 and was first funded in 2004. Its funding was minimal compared to the need but it started the ball rolling. The first, nascent steps to restore the Great Lakes were taken.

Emboldened by success, the advocates pressed on, recruiting factions like anglers, boaters and business interests to hop on the bandwagon, and they did. They presented a united front to Washington politicians and in 2003, legislation began brewing in congress to restore the lakes.

There were stops, pauses and re-starts, but by 2004 momentum had swung and President Bush issued an executive order – just like the ones that are eschewed today – declaring the Great Lakes a “national treasure.”

Federal money didn’t immediately flow but the Great Lakes were officially a national issue.

The table had been set.

By 2009, the formerly unknown Barack Obama was president.

As a candidate, he had pledged $5 billion for the lakes, and he put $475 million in his 2010 budget as a down payment. The federal funding spigot was officially open and long overdue work could begin.

What is Great Lakes Restoration?

The advocates didn’t want a piecemeal plan that lacked a strategy. They wanted – and got – a comprehensive effort that touched every corner of the Great Lakes region and most of the problems.

Excluded – by design – was infrastructure, but everything else was on the table. Cleaning up those legacy Areas of Concern, restoring wetlands, opening waterways by tearing down dams, improving beach health and habitat and more.

The initiative is run by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency but spans 16 federal agencies including sub-agencies.

That’s a lot of federal bureaucracy and that’s either good or bad depending on your perspective.

Good – if you believe it takes the full weight of the federal government to support restoration. Bad – if you question the ability of the federal government to deliver on a program of this magnitude.

The big players are the U.S. EPA, overseer of the initiative plus the Army Corps of Engineers, the Department of Agriculture, Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, more commonly known as NOAA.

A document sourced by Great Lakes Now from the U.S. EPA’s Great Lakes office website lists 3,455 restoration projects totaling $1.8 billion since the initiative’s funding began in 2010. The totals include funding updates to continue projects in progress but are not yet completed.

U.S. EPA accounted for 921 projects totaling $721 million. Fish and Wildlife Service had 814 projects for $256 million and the Army Corps of Engineers 550 projects, $191 million.

On the low end, the Center for Disease Control had four projects totaling $2.9 million. Yes, the CDC is involved in restoring the Great Lakes. It’s checking to see if water-borne pathogens – bacteria – are underreported in the region.

The scope of funding is wide ranging. A $5.9 million U.S. EPA grant to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to “reduce harmful algae blooms” would be one of the larger awards. A $3,000 project for “site characterization work” in Wisconsin is at the low end.

Most of the big-ticket items, though, relate to cleaning up the toxic Areas of Concern sites like the Grand Calumet and Sheboygan Rivers. Both of those were in the $11 million range or more.

There are a multitude of projects in the $100,00 to $500,000 range to support green infrastructure, build capacity to do restoration work, and for monitoring and assessment.

Success, failure and pork?

To have a continued stream of federal funding over time, recipients of the money have to produce results. They have to demonstrate success, and there is ample evidence that GLRI has delivered results. Though on occasion beauty is in the eye of the beholder; or in this case, the grant recipient.

The Healing Our Waters Coalition is the regional group that advocates for federal funding for the Great Lakes and it keeps a running tally of “success stories.”

The list is long and the advocates regularly use it to brief key members of the Great Lakes congressional delegation when funding comes up for renewal.

If GLRI has had a failure, it’s the tens of millions of dollars spent to incentivize farmers to limit their nutrient runoff to Lake Erie. That runoff fuels harmful algae blooms.

The U.S. EPA programs are voluntary and even the advocates for restoration funding recognize that it isn’t working.

A coalition led by the National Wildlife Federation recently sued the U.S. EPA for failure to have Lake Erie officially declared “impaired,” – essentially saying that the EPA didn’t comply with the Clean Water Act. An “impaired” designation could lead to limits on how much nutrient runoff farmers could send to the lake. The coalition says the EPA’s “foot dragging has to stop.”

As with any federal program the size of GLRI, there are the inevitable questionable projects.

The city of Wilmette on Chicago’s affluent North Shore was awarded $8,000 to plant trees near Lake Michigan to intercept rainwater before it could reach Lake Michigan. A reasonable person could assume that Wilmette didn’t need $8,000 in federal funding to plant trees.

And the Chicago Park District was the beneficiary of approximately $7 million for work on a “habitat development” project for Chicago’s Northerly Island, the spit of land (not actually an island) near Chicago’s Museum Campus. Nature in the city is the idea.

But the Chicago Park District had previously said before receipt of the GLRI funding in a 2009 video that Northerly Island was a “hidden oasis,” a “nature area… with a huge prairie” and a good spot in the city for “birding.” The $7 million project went forward anyway.

Universal agreement on federal funding but …..

It’s hard to find Great Lakes observers who don’t support federal funding for the lakes and that includes policy expert Dave Dempsey and legal expert attorney Noah Hall.

Dempsey spent six years as a policy adviser for the International Joint Commission and Hall is a Wayne State University law professor who founded the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center.

Both have a long tenure related to Great Lakes issues and are critical thinkers who don’t readily gravitate to anyone’s approved talking points. They are widely respected in the community of advocates, elected officials and administrators.

While supportive of federal dollars for the lakes in general, both are circumspect on funding. Instead they say of greater concern is the threat to regulations and enforcement.

Dempsey says President Trump’s rollback of Obama-era policies like the Waters of the United States rule and the Clean Power Plan (think Paris Accord) may have a far greater negative impact on the Great Lakes than the elimination of federal funding.

And Hall said as far back as 2009 that the Great Lakes would be better-served if even a fraction of the federal funding for restoration was spent on enforcing existing laws. He maintains that position eight years later.

As a candidate and as president, Trump has stated that the U.S. EPA regulation and enforcement activities are a major impediment to economic growth and he’s determined to eliminate or weaken them.

Where to from here?

The battle lines have been drawn.

The Trump administration’s proposed budget provides no more money to restore the Great Lakes. Its budget narrative noted the federal funding ($2 billion is the working number) to date and says that’s enough. It’s time to turn the work over to the states who have the capacity to do it, Trump budget director Mick Mulvaney has said.

The broader Great Lakes community including not-for-profit advocates and others are steadfast that restoration needs and deserves continued federal funding of $300 million annually. There is, in general, bi-partisan congressional support for restoration funding.

That bi-partisan support does not exist when it comes to regulation, enforcement and confronting business interests. There’s no bi-partisan outcry over the executive branch’s dawdling on a permanent solution to stop Asian carp, and politicians from both parties are loathe to confront farmers on nutrient pollution.

Obama as mediator?

Clearly, it won’t happen, but what if former President Obama could mediate the dispute?

After all, he’s been on both sides.

He put $475 million for the Great Lakes in his 2010 budget and it was approved by congress. And he cut it to $300 million a few years later under budget pressure from Republicans who had won a majority in the House of Representatives.

In ten years federal funding for Great Lakes restoration has gone from near zero under Bush to as high as $475 million under Obama. Trump wants to take it back to zero.

Is Trump right that $2.2 billion is enough and it’s time to revert responsibility back to the states? Is the Great Lakes community right that continuation of federal funding at $300 million is the only way to go?

Should there be a compromise?

Federal budget issues of all stripes including for the Great Lakes are scheduled to be resolved by September 30 when the new fiscal year begins. That date often slides depending on the willingness of disparate negotiators to compromise.