From the new outdoor adventure memoir I Live Underwater: The Thrilling Adventures of a Record-Breaking Diver, Treasure-Hunter, and Deep-Sea Explorer by legendary diver Max Gene Nohl. Below is an adapted chapter titled “This is it,” reprinted with permission from the Wisconsin Historical Society. In this chapter, Nohl tested an early version of the underwater breathing apparatus during a record-breaking dive to the bottom of Lake Michigan.

They had located the Lusitania.

However, it was now October. The full fury of the North Atlantic had broken loose, and its mighty seas were sweeping over her long-hidden grave as if to display the scorn that Father Neptune flays before those who would rob his dead.

The summer had gone, and we had long known that no one would ever work in those unprotected waters as late as this. The Orphir had been tossed about like a chip in Captain Russell’s last frantic attempts.

We, waiting and building equipment in this country, had long since realized that the summer was gone, although we had been ready to leave at a moment’s notice. Dr. End aptly expressed it when he said, “I wore out three suits of clothes just packing and unpacking them.” In the meantime, we were building new cameras and diving equipment.

The suit was ready for deep water, and I was itching to get down into it. Lapping up into our front yard at Fox Point, a suburb of Milwaukee, were the frothing seas of Lake Michigan. For too long, I had looked out at those waters and prepared to go down deeply into them — it was now time to do it. It would be next spring before we could use the Orphir, and so we looked around to see what we could get in floating equipment out of Milwaukee.

I had, in the meantime, hit three hundred feet and felt as fit as a fiddle last spring. Three hundred feet! That was “only one lousy little fathom” — just six feet — less than the world’s record.

There were still a few more test dives to be made in the summer’s improvements to the suit, but of most importance, there was the problem of getting down into the unknown. Studying the charts, I found that by heading northeast from Milwaukee toward a point about thirty miles out, we could hit almost four hundred feet of water, a depth not too easy to find in Lake Michigan.

I was anxious to have a good crew up on deck for this dip down to a depth that I didn’t know much about. It would be December and bitter cold out there. We had to have facilities for keeping the boys up topsides warm. No bobbing little cabin cruiser would do for this job.

The United States Coast Guard had been good to us and had allowed us to do our broadcast last April from their cutter Antietam. Perhaps, through the same channels, I could get it again. I went down to see Ken Fry, director of special events in Chicago for the National Broadcasting Company. He had done most of the arranging for our broadcast from the SS Norlond when Johnny Craig had snarled himself up.

“Of course,” said Ken, “I’ll see what I can do — not only that but how about taking an NBC microphone down with you?”

Allmendinger wreck off Mequon 1934. (Photo Credit: Milwaukee Public Library)

That was a hard invitation to pass up. Ken fixed everything.

A few days later, a huge NBC truck came roaring up to Milwaukee, and we all piled in and drove north to the city of Port Washington. This would be the closest town to the chosen diving location. At the very crest of the characteristic hill of Port Washington was the Catholic church, with its massive steeple towering skyward. “What a place for an aerial!” cried the engineer as he spied the lofty structure. The broadcast, similar to the other, would be sent ship to shore by shortwave and then telephoned into Chicago to feed NBC through its key stations.

The Antietam had always looked enormous to me, perhaps in contrast to our own small boats. However, it didn’t look so big on the morning of December 1, 1937, the day appointed for the dive. There were swarms of people practically pushing each other into the river trying to get on board. We couldn’t figure out from where the leak had come, since we had decided there would be no advance publicity — just in case I couldn’t make it.

Captain Whitman, able master of the Antietam, trimmed them down in short order, picking out representative reporters to cover the story, who would share it with the others on return. He chose representative still photographers and the skeletons of four newsreel camera crews. Every one of them had a wild gleam in his eye — someone was going to get killed today, and what a story that would be!

The broadcast was to be at 1 p.m. In time, Captain Whitman called out to his crew to shove off. The Antietam’s bow slipped out into the stream of the ice-choked Milwaukee River, and in a moment, we were off. Bridge after bridge swung open for us, and soon we were cutting the ripple of the outer harbor. In a few minutes, we felt the deck take life beneath our feet as our bows emerged through the breakwater into open lake.

I had planned to hit 360 feet today, the next logical increase after my previous 300-foot dive. This would be 54 feet deeper than Frank Crilley’s record made twenty-two years ago and would be ample margin to officially prove the superiority of helium over air. Thus, I asked Whitman to try and anchor in as close to sixty fathoms of water as possible.

I could hear the soundings being sung out. “Fifty-seven, sir.” “Fifty-seven, sir.” “Fifty-seven, sir.” “Fifty-eight, sir.” “Fifty-eight, sir!”

We had been proceeding so cautiously that suddenly we realized there was very little time left. It was important that we be in location before one o’clock and that I be in the diving suit ready to go overboard as we joined NBC. Captain Whitman well realized this and knew that he would have to speed up his sounding operations. His vessel had been coming almost to a standstill to run each sounding. In a quick extrapolation on the basis of the apparent gradual slope beneath us, he ordered a spurt of speed to take us in one stretch to the desired depth. A sounding was taken. “By the mark, seventy, sir!” came the report. The contour had changed. The bottom had dropped off more rapidly. We had 420 feet of water beneath us.

Whitman looked at his watch then looked at me. “We have your 360 feet of water beneath us,” he said, “and also 60 feet to spare.” He looked at his watch again. “There is no need to go all the way to the bottom. You can stop at your desired depth. It’s going to take a little time to get our anchors laid. We don’t have time to look anymore.”

I reluctantly agreed. He was right — 360 feet of water are 360 feet of water, regardless of whether I would be standing on the bottom or just hanging on a rope. Somehow, it didn’t seem quite the same — but it was too late now to search for the exact depth. If only there hadn’t been so much confusion when we were ready to sail as to which reporters could go and which would have to take the story secondhand.

Over went the anchors. The Antietam maneuvered to feel their bite on the bottom, a check sounding was made, and the previous depth confirmed: “By the mark, seventy, sir.”

Everyone was busy. The Coast Guard boys were getting out the anchors, the radio boys were checking their cue channels, our diving gang was making last-minute adjustments on the gear, the cameramen were getting ready for the kill, and I was squirming into the rubber dress.

The temperature was not much above zero. A biting breeze was blowing across the winter lake, relentlessly penetrating every stitch of clothing anyone could wear. The lashing spray from the angry waves was freezing on everything. There had been many massive cakes of ice through which we had plowed coming out. In short, it was a miserable day on deck.

Diving under the ice. (Photo courtesy of Kathy End)

Except for those few who preferred the misery of the wintery deck to the certain symptoms of mal de mer that came from stepping below, we had all found as much excuse as possible to stay in the warm interior of the ship. Now, however, it was time to venture out for all.

Shaking, they all, one by one, looked at me with a skeptical eye as to my mental condition — wanting to plunge down into that iced winter water on a day like this. In turn, at various intervals, every man on the ship finally ventured to ask individually just exactly what I had in mind, not saying in so many words that I was crazy but politely wondering why this must be done on a bitter December day.

The joke was really on them. While they each would suffer for me in a few minutes as I started down into the frigid waters, I knew that I would actually be the warmest one of the lot. There would be no wind down there in the first place, and I would have almost jumped overboard without the diving suit to get out of that merciless blast.

Secondly, the temperature would be considerably higher than it was up here on deck. Although to the popular mind the coldest thing on this earth is ice water, the sensation of cold is a result of its capacity to quickly conduct heat away from the body rather than its low temperature. It was probably about zero up here on deck, but that water I knew very well would not be below thirty-two degrees (Fahrenheit) — if it were colder than that, I wouldn’t be going down into it except with an ice pick.

Under the diving dress, I was wearing a warm lambswool garment made very much like a baby’s sleeper suit, plus several pairs of “long handled underwear,” and wool socks. Unless I should spring a leak, it would be quite comfortable.

It had been decided that we would open the broadcast on deck, just as the helmet was being clamped on over my head, and that I would be on my way to the bottom within the first few minutes of our allotted time. We would have 30 minutes, and they seemed very anxious to make sure that I would be in 360 feet of water during that time. They wouldn’t say so, but from the gleam in their eyes, I knew what they were thinking — they wanted to broadcast my death rattle and to make sure that they were on the air when it came.

Everyone took his station as the starting moment approached. Norman Barry, NBC’s suave and handsome announcer, was to be the commentator. Ivan Vestrem, my faithful diving associate, was to take charge of tending my lines and getting me in and out of the water with the full facilities of the Coast Guard crew at his disposal. Captain Whitman was in charge of the vessel, Ken Fry was in charge of the broadcast as a whole, and Dr. End was to stand by for emergency consultation and co‑commentating with Norman Barry.

Then came the fifteen-second hush signal — and except for the breaking seas, there was not a sound. Ken Fry’s raised hand then dropped, and we were “on the air.”

“Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen,” started the smooth, genial voice of Barry. “We are bringing to you this afternoon a unique broadcast.”

He went on to explain where we were, the sensation of being at sea on a day like this, and what we were planning.

Frequently consulting Dr. End or asking him to explain or elaborate on some point, Barry described the experimental work we had done with helium at Marquette University, the guinea pig test dives and how they had shown us helium’s effectiveness and how we were now planning to test this suit at a depth which no human being had ever before reached.

The Lusitania story was told — how she had sunk in 1915 and been found during the past summer at a depth of 312 feet off the Irish coast. It was also told how, curiously enough, in that same year, 1915, almost a quarter of a century ago, the United States Navy diver, Frank Crilley, had reached a depth of 306 feet to establish the world’s record for deep-sea diving, which I planned now to try to exceed.

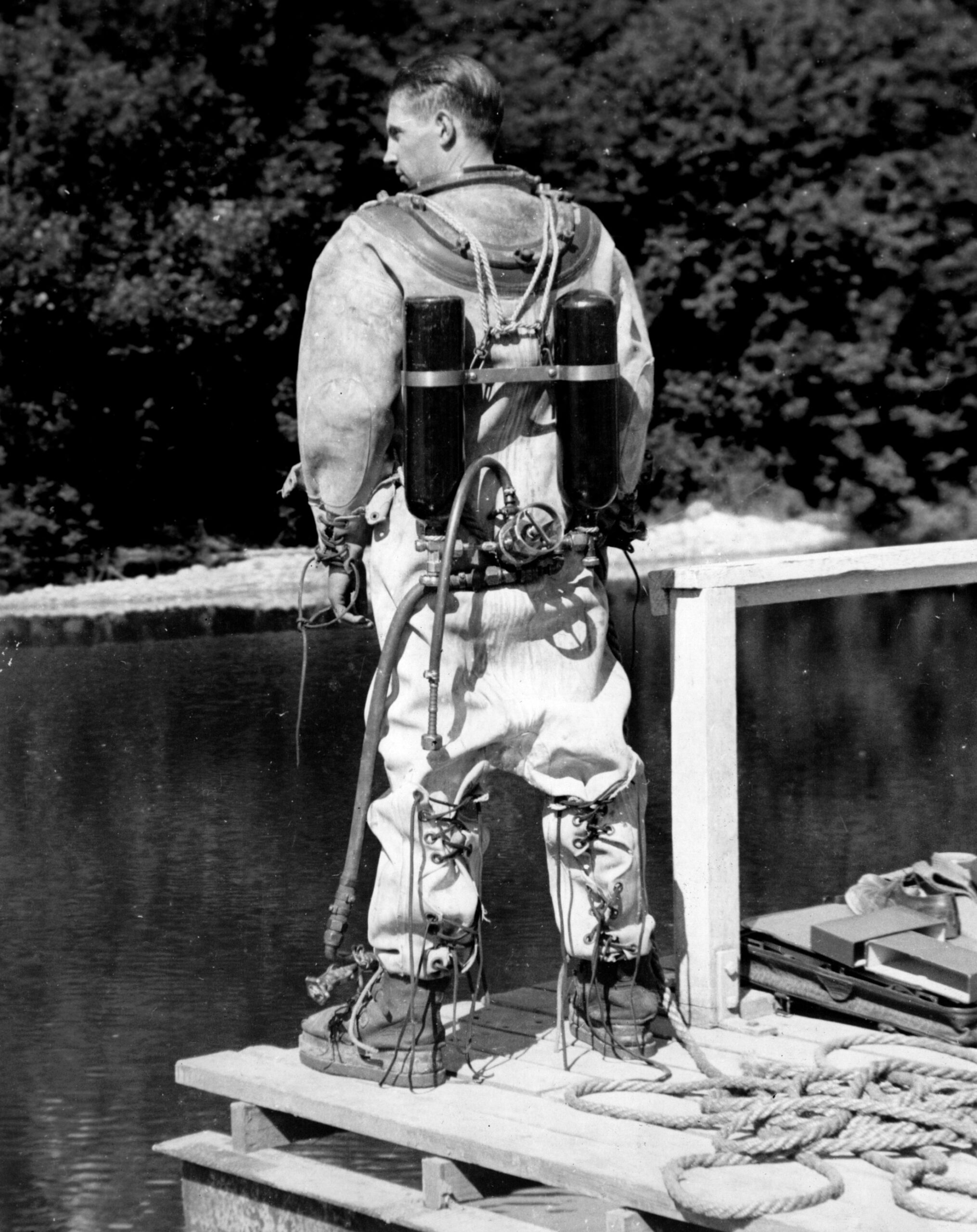

Self-contained droopy suit. (Milwaukee Public Library

“Are you ready, Max?” asked Barry, as he finished with his preliminary explanation.

I was ready, and as I said it, I felt the clank of the tools in the last tightening of the diving dress to the helmet. Vestrem called the “Haul away!” signal, and in a moment, I felt myself being lifted off the deck into space. I slumped down into the suit and relaxed to listen to my own broadcast I could see nothing, since the window was badly fogged, my breath and body humidity freezing on the zero-temperature glass. Barry now started asking me questions, and I could now devote my full attention to carrying on a conversation.

Helium is tasteless, odorless and colorless. In answer to the frequent question, “How do you know it’s there?” is a suggestion for a simple and startling test. Take a deep breath of the gas in question, and then start talking. If it’s helium, you will know it right away. Because of its low density, it has a decidedly different period of vibration than the same quantity of air in the larynx, just as a light, thin piano or guitar string has a different note than a heavier one. With every attempt to talk in a natural voice, out comes a high falsetto that gives a very funny effect.

Thus, the conversation with Barry was a strange one, with my helium-pitched voice and the heavy reverberations of the helmet interior.

Suddenly, I heard a gasp up on deck and in a split second felt my body splashing down into the water. The clutch on the hoist had slipped, and I had fallen the last ten feet for an unexpectedly quick entrance into the lake.

There was much excitement up on deck, which I could well hear over the telephones, everyone apparently thinking I must be dead from the fall in the huge 288-pound suit. Actually, I had hardly noticed that I was dropping, the weight of the suit giving me the inertia to plunge into the gradually retarding water with a softness that no feather mattress could boast. I bobbed up and down in the water a few times before coming to a rest with my window just under the surface.

I next rubbed the fog from the window with my “rubber nose” and saw directly in front of me the massive hull of the Coast Guard cutter.

Barry, still thinking that I was badly injured from the accidental fall into the water, seemed much concerned. This, however, is the way we usually go overboard anyway — we just jump in — and although it had been a surprise, it was not detrimental to the dive in any way.

I called, “Slack away,” and heard him repeat the order to the boys on deck. I started down, the descending line running through my mittened hands. Although this was a self-contained suit, on this experimental dive, I decided to have a lifeline snapped to the helmet top. Since there was a microphone, it would be necessary to have the wire at all times anyway, and so Vestrem had previously bound the two together. I had a typical December head cold and was afraid that I was going to have trouble clearing the mucus from my Eustachian tubes. Thus I was also using a descending line, which I could use as a trolley to hang to in the event that my ears didn’t clear. It would also give me something on which to hang to offset the deep lake currents.

Vestrem had apparently entrusted the actual tending of my lines to one of the Coast Guard boys while he attended to numerous other details on deck. One of the difficulties a diver is likely to have with inexperienced tenders is that they take too good of care of him, gingerly and painstakingly feeding out his lines, inch by inch, to greatly impede his progress.

The diver, actually, is always anxious to reach the bottom as fast as possible — if any deceleration is necessary to save his ears, he can perform this himself either by clinging to the descending line or by lightening his suit.

Max being lowered down. (Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)

“Slack away!” I called. It seemed they felt that they were feeding me down into what must look like death itself on this icy day. I went down a few feet and then found myself barely sinking.

“Slack away!” I called again, and again, and again! Finally, I paused to explain in full detail what I wanted, which was no restraint on the lines whatsoever — I wanted to control my descent myself.

This, apparently, worked. I started down like a plummet.

A pain struck through me like a streak of lightning — a “clinker” must have jammed up in my left ear. I frantically clutched for the trolley to stop myself, but my inertia was so great that, before I could come to rest, I almost lost an eardrum. The pain was so intense that I climbed back up a few feet where I immediately found relief with the lessened pressure. I swallowed, coughed, yawned and tried everything in the book, but to no avail. Up again and down again, up again and down again I bobbed, but with no results. In shorter cycles, I rapidly plunged my body like a piston at that barricading depth, but I could not pass it however hard I hammered.

I went up a few feet higher for a battering ram blow, but at exactly that same lower level, the streak of lightning hit me again and effectively made it impossible for me to go deeper.

It felt as if someone had driven an axe-head through my skull. What a ridiculous thing! On this, of all dives, my ears wouldn’t cooperate.

I decided to just wait. Barry was asking a lot of questions. I selected a depth where the pain was just as bad as I could stand it and then moved an inch deeper. In this way, there would be a maximum push on that clinker. We talked about ears, helium, the Lusitania and why I was not going down any farther at the moment.

I suddenly found myself viewing, through the expansive window of the helmet, a strange sight. Passing rapidly downward in the trackless blue-green water was a bright yellow manila rope. I studied it for a moment to attempt to determine what it possibly could be — it was my lifeline!

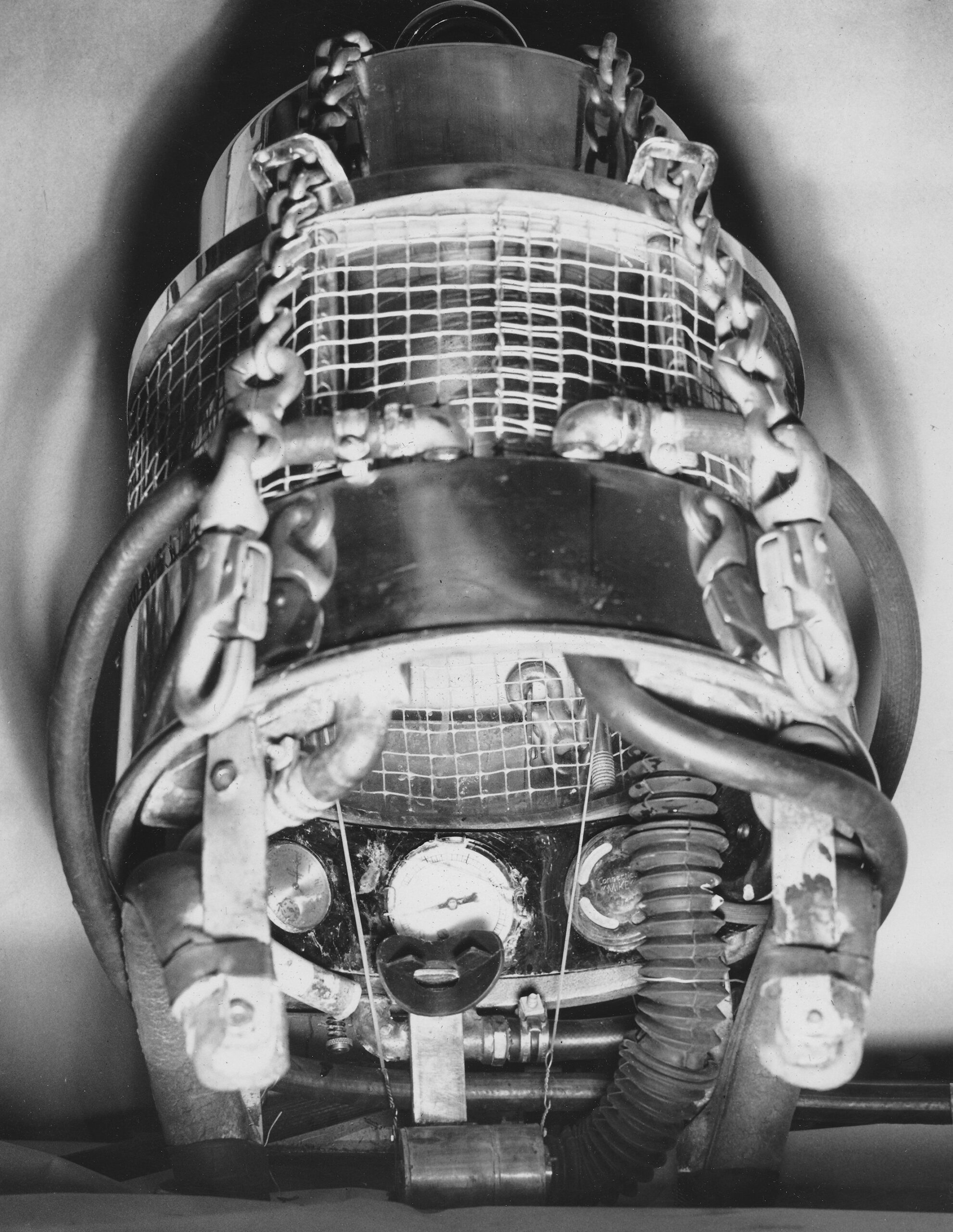

Dive helmet detail. (Photo courtesy of Kathy End)

I tried to explain this to Barry — that the boys were now giving me too much slack and that I wished that they would now take in the excess. In a moment, I saw the line going the other way.

We continued to talk, and I was beginning to realize that the attempt to break the record would be a failure, not because of any reflection on the helium or the new suit, but just because of a stubborn clinker in my ear. At 220 feet, I was only 86 feet from Crilley’s record, but progress was now limited to a maximum of a few more inches.

Suddenly, there was a sharp click in my head. The almost unbearable pain vanished as if a fairy wand had been waved over me. The transformation from torture to what was now a crystal-clear head was as instantaneous as the wink of an eye.

I started down into the stygian gloom below. On my extended sojourn at 220 feet, I had enjoyed the last trace of deep-purple light in the water, but in a few seconds even this vanished into what might as well have been a mammoth pool of India ink.

At 240 feet, my clinker came back momentarily, and I stopped again. This time, however, it was just temporarily stuck, and a moment’s yawning pushed it on its way. As I hung to blow those tubes, I felt again the drooping coils of line sagging down on me. The boys were still feeding out too much slack.

We only had a half hour on the air, and I was determined to reach 360 feet before it was over. I decided to request that Vestrem, who had had his hands overfull with other details of the diver, hereafter personally handle my lines. I must be in quite a snarl already. Vestrem agreed to take over.

I started down again, blowing every possible cubic inch of extra gas out of the dress to give myself as much weight as possible and asking for full slack on the lines.

For a moment, I thought that I was descending — purely an imaginary sensation since I had nothing with which to compare my relative movement. Grasping the descending line, which I now held loosely in the crook of my arm, I noted that it was not moving — I was standing still. There was no way in which I could increase my weight any further. I asked Barry to check whether I was all slack.

“All slack,” I could hear Vestrem sing in the distance. “All slack,” repeated Barry into the microphone.

Perhaps I could pull myself down as I had often done before in strong currents.

I reached down and grabbed the line as low as I could and started pulling. I moved only a few inches. Another pull, and I progressed a little further. It was like pulling a too-tight ring off a finger; though I seemed to be moving, I was slipping back eleven inches for each foot of progress I was making. I pulled harder and harder, almost frantically lunging at the line. I was just about in the same place five minutes later. I was also panting.

Perhaps I could climb up a little ways and find the snarl that was holding me. I reversed my efforts and found that I could not move up. I tried to move down again and then up again.

I was stuck — stuck at 240 feet in total darkness. I was exhausted.

During these struggles, I had tried to carry on a conversation with Barry but had been so busy that I had not had much to say other than to answer his questions. He had been warning me that we were running out of time. And now I heard the words that I had feared, “We regret, ladies and gentlemen, that our time is drawing to a close and that we will have to conclude this broadcast with Max Gene Nohl at a depth of 240 feet on his attempt to break the world’s record for deep-sea diving. We are broadcasting from the United States Coast Guard cutter Antietam. This is the National Broadcasting Company.” And then over the phone came, “We’re off the air — what’s wrong?”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Fact or Fake? Readers can test their Great Lakes knowledge with excerpts from this new book

New Great Lakes book challenges readers with mystery, facts and whimsy

Featured image: Cleaning windows. (Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)