Since assuming the helm of Milwaukee’s sewerage agency (MMSD) in 2002, Kevin Shafer has been focused on managing and expanding the city’s deep tunnels designed to keep sewage out of Lake Michigan.

Knowing that tunnels alone are not enough, Shafer also started a campaign to emphasize green infrastructure and over the years, Milwaukee went from having a reputation as a bad actor to being a national leader in managing sewage overflows.

Shafer — a graduate of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign — is a civil engineer by training with expertise in water resources.

But in 2018 a new challenge was emerging, one that was out of the agency’s lane, but Shafer nonetheless decided to take it on.

He got involved in a local movement to clean up the decades-old, two million cubic yards of contaminated sediment in the Milwaukee Estuary, the junction of three rivers that empty to Lake Michigan. The estuary is on a federal 1987 list of officially designated Areas of Concern still to be remediated.

The EPA has funding to clean up sites like the estuary but there’s a catch. Access to federal funds requires that 35% of the cost be borne by local entities.

Great Lakes Now recently spoke with Shafer where he described what came next.

Build it

The proposal was to build a containment facility for sediment removed from the estuary.

As the group continued to meet, “no one was stepping forward to take the next step,” Shafer said, and he knew he had the people, resources and financial capability to build the facility.

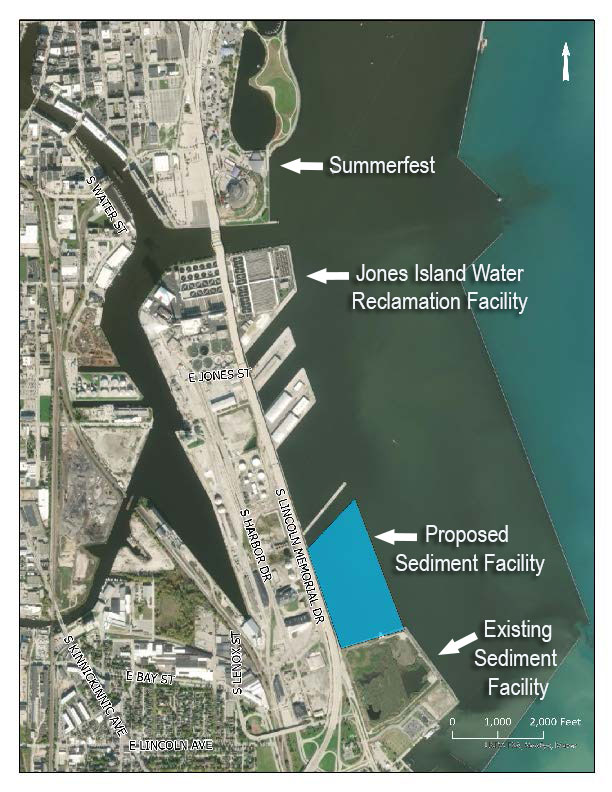

Site for storage facility. (Photo courtesy of Gary Wilson)

MMSD had been on a steady path to improving the environment and public health and Shafer said, “it just struck me that the next step was to get rid of the contaminated sediment at the bottom of the estuary.” He saw that as aligned with “the agency’s mission to protect Lake Michigan.”

Shafer told the group MMSD could do the work and generate the required local funding match, and then met with local leaders and elected officials. “They really wanted it to happen and they thought MMSD was the best entity to do it,” he said.

With that, Shafer became the de facto leader of the project and construction of the dredged material management facility became the linchpin.

Without MMSD stepping up, “the whole Area of Concern work could have unraveled at that point,” he said. Plus, there was a sense of urgency because there was no guarantee federal funding would be available in the future if the project languished.

The storage facility is substantial and the project will be high profile given the significant federal investment. Great Lakes Now asked Shafer if he was confident of MMSD’s ability to deliver. “MMSD doesn’t do small projects,” he proclaimed. “It does big projects that make an impact on the community in a positive fashion.”

Questionable location

The proposed toxic sediment storage facility will be near the site of the existing one, which is near capacity. Both are in close proximity to Lake Michigan.

As the facility will be in place for decades, Great Lakes Now asked Shafer about the efficacy of siting the new facility where it will be exposed to climate driven extreme weather events that can cause flooding and erosion, plus the threat from fluctuating lake levels.

Shafer defended the decision saying “in the design of the facility steps were taken to ensure that they are as prepared for climate change as best as anyone can tell us what it will be.” He feels the facility will protect Lake Michigan and said he “wouldn’t be pushing for it if he thought it would affect Lake Michigan.”

“The contaminated sediment is in the lake right now,” Shafer said, and if you move it away from the lake it ends up in someone else’s watershed. There are risks with disposal of the sediment no matter where it is.

Milwaukee riverkeeper Cheryl Nenn tracks the estuary and said in an email that “removing toxic sediment from the bottom of the rivers—outweighs the negatives, which in this case is creating a new sediment facility at the lakefront.”

Nenn said the public understands that the sediment needs to go somewhere and the proposed site is the best of no great options.

Yet there are examples where there’s been significant local pushback on this kind of project.

In Chicago, community groups represented by the Environmental Law & Policy Center are suing the Army Corps of Engineers over its plan to build a similar sediment storage facility on the Lake Michigan shore in Chicago’s Southeast side.

The suit alleges the Army Corps failed to evaluate certain environmental risks or consider alternate sites. One of the plaintiffs, Friends of the Parks, maintains the facility is a remnant of previous eras’ zoning and environmental policies. The organization is best known for its successful challenge to building movie mogul George Lucas’ Museum of Narrative Art on the lakefront.

“It is a travesty to continue to designate prime lakefront park land, that is next to other parks and beaches, for a toxic dump,” the group’s executive director Juanita Irizarry said in a press release.

Advice for Detroit

The Detroit and Rouge rivers are also on the list of Areas of Concern and the Detroit River alone contains approximately 3.5 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment, far surpassing Milwaukee’s estuary.

Clean-up has lagged and the state of Michigan has not been willing to invest.

Recently, a group of 60 concerned entities wrote to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and legislative leaders requesting the state contribute approximately $100 million to the required non-federal match. The letter expressed a sense of urgency because federal funding soon may be unavailable and the entire cost of the cleanup would fall to state and local entities.

However, as reported in the Detroit News, the $100 million was not included in the state’s 2024 budget, with a key legislator calling it a challenge, citing other funding demands.

Great Lakes Now asked Shafer for his advice to people in Detroit involved in sediment remediation projects stuck in neutral.

“Every project needs a champion, someone who will step out and garner the troops together,” Shafer said. Once you have that champion, that person can talk to federal and state governments and various local government entities including the business community, he said. “You need that type of person to lead the way.”

In the meantime, the next step in the Milwaukee estuary process is already underway — to select a contractor to construct the facility. That doesn’t mean it will be smooth sailing from now on. Inflation will be an issue, as will the budget process given the divided Congress, with House Republicans pushing for big cuts.

Still, Shafer is optimistic: “My approach right now is this facility will be built and it will be ready to take those sediments once it’s done.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

New University of Michigan led initiative expands climate research across borders

Michigan water rights advocate questions effectiveness of proposed affordability legislation

Featured image: Kevin Shafer. (Photo courtesy of Gary Wilson)