Running a Great Lakes fish hatchery requires a thorough understanding of biology, an affinity for mathematics, a solid grasp of physics and engineering, enough plumbing skills to qualify for union wages and a stomach impervious to the aroma of stinky fish.

Kris Dey has been running the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians’ fish hatchery for five years. The Little Traverse Bay Band is a federally recognized tribe whose historically delineated land encompasses approximately 336 miles in the northwestern tip of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.

The primary objective of the Tribe’s $2.5 million hatchery is to help native Great Lakes species. This year’s goal is to raise and release over half a million fish.

The specific fish they focus on depends on the year.

“Our target is 500,000 whitefish, 1,000 sturgeon and up to 60,000 walleye,” Dey said regarding this year.

The hatchery had been rearing and releasing up to 85,000 ciscoes, or lake herring, into Lake Michigan each year, but that program was suspended in 2020 when surveys showed the lake’s population of ciscoes was naturally increasing. Dey said if the number of wild ciscoes begins to drop, the hatchery will start raising them again.

Kris Dey, hatchery manager of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians’ fish hatchery (Photo Credit: Kathy Johnson)

“It kind of seems like the whitefish need us more right now,” he said.

But supporting native species isn’t as simple as just rearing and releasing fish – allocating resources is just one of the challenges of hatchery management.

Balancing the needs of different species is another of those challenges.

Whitefish vs lake sturgeon

Whitefish hatch in near-freezing water temperatures. They spend their entire lives in cold water and are very intolerant of warm water, according to Dey. Just a few degrees too warm and whitefish start to die.

Whitefish swim in the big open waters of the Great Lakes. At the hatchery, whitefish are raised in large circular tanks with flow-thru water systems that function as fishy treadmills and automatic tank cleaners.

“The tank has to be twice as wide as it is tall for a proper radial flow to form,” Dey said.

The radial flow, also known as the teacup effect, swirls the water through the fish tanks like the spiral that forms as bathtub water empties down the drain.

The interior walls of the 8-foot diameter tanks are painted a soft baby blue. Inside, hundreds of thousands of whitefish continuously swim against the swirling flow in never-ending laps.

Fish waste naturally drops to the bottom where it is swept up and out the drain by the swirling water. This self-cleaning mechanism greatly reduces the amount of tank cleaning required of the hatchery staff.

The sturgeon tanks are managed quite differently from the whitefish teacups. Sturgeon are benthic, meaning they live on or near the bottom. The water in their tanks is circulated through at a much gentler rate to avoid the teacup effect forming too strongly. It needs to be just strong enough to keep the water moving and the waste flowing out the drain without flushing the tiny sturgeon away.

At feeding time, the flow in the sturgeon tanks is stopped altogether to prevent their food from getting swept down the drain before the fish have time to eat it.

Dey said the number of sturgeon per tank is also determined by how much area is available on the bottom of the tank rather than by the amount of water the tank can hold as with whitefish, walleye and ciscoes.

Dey said the most important factor when raising any species of fish is oxygen. Every tank has a probe monitoring the oxygen level. If the amount of oxygen in the tank drops below a preset point, the automatic feeder will stop. When fish stop eating, their metabolism slows down and they require less oxygen.

If oxygen levels continue to drop, alarm bells sound and text alerts are sent. The need for quick response times by hatchery staff makes living within 20 minutes of the hatchery a requirement for employment.

Oxygen isn’t the only critical factor. Maintaining a steady food supply is so important that Dey said they have multiple backup systems for the fish food.

Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians’ fish hatchery (Photo Credit: Kathy Johnson)

Food chain

A small storage room inside the hatchery houses a larger chest freezer packed with frozen blocks of krill and shrimp.

Two walk-in freezers at the LTBB Natural Resources office warehouse a one-year supply of fish food. Stockpiling an entire year’s supply of fish food proved critical in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic created massive delays in the global supply chain.

Raising half a million fish takes a lot of food. Dey said his most recent shipment of bloodworms was 175 kilograms, about 385 pounds, which should be enough to feed the lake sturgeon for the next year.

Recently, Dey heard the Michigan State University hatchery was using krill to feed their larger sturgeon. Krill are small ocean crustaceans that make up a significant portion of many marine animals’ diets, including whales and penguins. Dey ordered 10 packages of krill in varying sizes to try with his sturgeon.

“They really like it,” he said, adding that krill is also much cheaper than the bloodworms they were using.

Just as critical as the right kind of food is the right amount of food.

When the LTBB first started raising sturgeon, the mortality rate of the larval fish was unexpectedly high. A call to the MSU hatchery manager provided a possible solution – Dey might be overfeeding.

Giving lake sturgeon too much food can cause them to starve. This behavior is so counterintuitive, Dey said it never occurred to him to give staving fish less food.

When he reduced the number of feedings the sturgeon received each day, the fish started eating properly and stopped dying.

Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians’ fish hatchery (Photo Credit: Kathy Johnson)

Seeing the light

Experimentation is an important part of Dey’s job. The LTBB hatchery operates on a much smaller scale than some state hatcheries. Dey said running a smaller facility allows him to experiment in ways that larger operations sometimes can’t.

The industry standard for hatcheries is to rear fish in windowless buildings with only enough light for the staff to work safely. Multiple hatcheries had tried to raise cisco in these near dark conditions and failed miserably.

“Cisco need light,” Dey said.

Ciscoes are extremely photosensitive, and Dey said when doing surveys, the ciscoes are often found closer to the lake’s surface than the bottom. Knowing that ciscoes can be found near the surface should have been a clue that they liked light, but Dey didn’t figure it out until the automatic shut-off controller for a set of work-lights failed.

“The lights stayed on, and our cisco mortality went down,” he said.

Dey began experimenting by turning on different banks of lights for a week at a time. The closer the lights got to the ciscoes’ tank the fewer the number of fish that died. When he left the lights on directly over their tank, for the first time in captivity the ciscoes finally began to thrive.

Doing the math

The dreaded word problems that many students fear seeing on math tests are a daily part of hatchery management. Nearly every aspect of Dey’s job requires a high degree of mathematical calculations.

If a one-inch fish can eat an ounce of food per day, how much food is needed to feed 500 two-inch fish? What about 15,000 four-inch fish? Don’t forget to factor in that small growing fish eat more by body weight than larger fish.

The math is endless. From how much freezer space is needed to hold a one-year supply of fish food to clipboards filled with dissolved oxygen levels and tank capacities for future data analysis.

Dey’s calculations begin before the first fish arrives.

“We start with the number of fish we want to release and work backward from there,” he said.

To stock 500,000 whitefish, Dey needs about 750,000 eggs to hatch.

For that to happen they need “close to one million eggs,” he said, adding that it takes approximately 600 adult whitefish for the staff to collect and fertilize one million eggs.

A bachelor’s degree in biology and an interest in working with fish are expected job requirements for hatchery work. But Dey admits it also takes a genuine affinity for math.

“If you left college and never worked with Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Access or the statistical program R, you’re gonna have a real hard time with a lot of what we do,” he said.

Dey doesn’t mind all the math. He’s even ok with all the fish tank maintenance. The only downside to hatchery work for him is when fish die.

And his favorite part of running a hatchery is the day they release the fish into the Great Lakes.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Grayling Revival: Researchers hope to reintroduce a once-abundant native fish

Speak for the Fish: Shell middens reveal interesting clues about the humble muskrat

The Farmory: Is indoor fish farming a viable way of tackling declining fish populations?

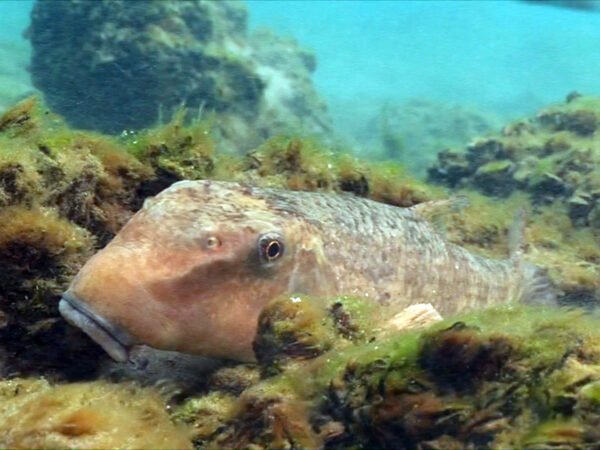

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Fish at the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians’ fish hatchery (Photo Credit: Kathy Johnson)