This is an excerpt from the book “The Great Black Swamp: Toxic algae, toxic relationships, and the most interesting place in America that nobody’s ever heard of.” Available for purchase on November 11, 2025, by Belt Publishing.

“The Worst Road in America”

Disasters do not happen overnight.

And rarely do they have a single source to blame for all their destruction. Rather, disasters are often the product of long stretches of negligence and bad decisions and optimistic best intentions that coalesce in a single catastrophic moment. In most cases, we don’t see those elements combining, or if we do, the alarms they set off tend to get overlooked in favor of normalcy.

Case in point: the disastrous settlement of the Great Black Swamp. It was a giant mess that kept getting worse for almost one hundred years before it got better, and its period of “better” would eventually lead to another disaster, the 2014 algae crisis.

The disasters begin with an 1830 roadway project. Up until then, the world at large seemed content to ignore Northwest Ohio. All one million acres of dark, deadly, impenetrable swamp may have remained an explorer’s curiosity if not for a city almost 250 miles away. Right as Chicago grew into the biggest, most important metropolis in the Midwest, the Great Black Swamp developed a big target on its back. Traders, travelers, and immigrants moving between New York City and the Windy City were losing time and money because of Ohio’s nightmarish upper left atrium. Pull out a map and notice how a straight line could practically be drawn between the two cities, except for Northwest Ohio.

Back in the early 1800s, wise travelers simply went around the Great Black Swamp. Those with a death wish tried to cut directly through Satan’s Backyard. Either route added days, or even weeks, to the trip. But only one could get you eaten by a wolf. So there was that.

However, America was in the midst of a Manifest Destiny conquering spree, which made Northwest Ohio seem like a simple equation to solve. This Buckeye State blight was standing in the way of progress, and nothing stood in the way of progress in the 1800s. Money was being lost! Worse yet, opportunities to make more money were going unfulfilled. This stupid swamp was sandbagging America’s greatness, and that would not do.

Since the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the same year Ohio achieved statehood, the country had been throttling steadily westward, not just exploring but taming its wild plains, rivers, mountains, and deserts. Nature or Natives be damned. So, it seemed almost like an afterthought that that America would soon bury this meaningless Ohio mud puddle. The Great Black Swamp was no match for our young nation’s optimism and energy!

The prevailing logic of the era said it would be a cinch: Just slice a path through Northwest Ohio connecting New York to Chicago. This would not just be some dinky roadway, but the latest, greatest money chute America had ever concocted. This thoroughfare would be an unfettered pipeline sending riches in both directions. Plus, it would lift this backwater part of the country into something respectable and normal.

Recall how, after years of lopsided treaties and bloodshed, native tribes had been pushed off their ancestral property and forced to take ownership of the Great Black Swamp. In a move both predictable and depressing, the government suddenly decided to take back what it previously determined was worthless, telling tribal leaders in essence, “You can still keep the parts we think are shitty. We just want this slightly less shitty section right here,” and ran a greasy finger through the gut of the Black Swamp.

By 1808, Ohio Senator John E. Hunt had led the purchase of a thirty-five-mile ribbon of Great Black Swamp for thirty thousand dollars. The plan was to create a nineteenth-century Ohio autobahn named the Maumee and Western Reserve Road. Speculators claimed great cities would spill outward along the road’s path. Others touted the region’s inevitable rise as an agricultural superpower; “The Garden of Ohio,” several publications predicted.

Construction didn’t truly begin until 1823. The first problem was getting rid of all those worthless trees . . . and hungry wolves, and endless pits of mud. And, yes, those malaria-filled clouds of mosquitoes should probably scram, too. No worry. America had grit and optimism on its side. Slowly, a 120-foot-wide path was carved through the swamp. All along the route, thousands of trees were left discarded in the crew’s wake and simply set ablaze. The tar-black smoke of progress must have filled the skies above Northwest Ohio for months, which left a crude roadbed of ash and charcoal behind. Shallow drainage ditches were dug along both sides of the turnpike. Horses and coaches would begin smoothly cruising east and west very shortly.

The Maumee and Western Reserve Road was finally finished in 1827 and quickly lived up to expectations. The road saw an immediate swell of traffic, at least 5,500 travelers in one year alone, which is an absolute explosion for such a desolate region. The government’s vision for the primitive superhighway was, by early accounts, a huge success.

As predicted, previously unsellable land near the road began to be snapped up with the intention of clearing and settling it. Thirty-one taverns were built along the thirty-one-mile route. One such speculator was a Columbus, Ohio, banker named David Deshler who purchased thousands of acres far south of the road, deep into no-man’s-land, and then sat on that worthless property, waiting for an opportunity to arrive.

Today, you can still find evidence of this doomed Maumee and Western Reserve Road construction project ten miles outside of Toledo, in Perrysburg. It doesn’t look like anything special today. It looks like the suburbs; a really cute suburb with a historic Main Street filled with charming brick buildings, bustling coffee shops, bakeries, salons, and restaurants, including the perfectly named “Perrysburgers.” Today, it’s an upper middle class bedroom community with treelined streets and charming Victorian homes. More than likely, folks here commute into Toledo for work, and, more than likely, they don’t realize their finely paved State Route 20 was, for a time, considered the biggest mess in American civil engineering history.

The only remains of Perrysburg’s section of the Maumee and Western Reserve Road is a triangle-shaped park about the size of a studio apartment. The park butts right up against all four lanes of Route 20, buzzing with bass-heavy stereos and the occasional semi-truck. The heart of the park is a small limestone pillar, on which the writing has eroded like an old grave. This is a mile marker for the Maumee and Western Reserve Road, and if you saw one of these back in the 1830s, it was a sign that you were probably having the worst day of your life.

Even though humans were slowly filtering in, the Black Swamp’s wolves were still fearless predators intent on defending their home. Fourteen-year-old Pony Express rider John S. Butler documented a time when an entire pack stalked him and a friend. They were forced to beat the wolves off with sticks only to have the rest of the snarling pack follow and attack through the night until they found a tavern for shelter. Others reported sleeping beneath an overturned wagon only to have its sideboards eaten away by the aggressive creatures. The wolves, it turned out, were just getting started.

However, a far more immediate problem was the road itself. The Maumee and Western Reserve’s popularity led to quick deterioration. Soon, it had acquired a national reputation of its own.

“You could hardly call it a road,” Glenn says in The Story of the Great Black Swamp, as the film shifts to sepia-toned photos of horses and carriages navigating what looks to be remnants of World War I battlefields, but are, in fact, Northwest Ohio. “By 1835 the quagmire had come to be known as the worst piece of road on the continent.” The Maumee and Western was virtually impassable.

The area tavern owners must have known this would happen, because during the muddy season a traveler could only slog forward about a mile each day, roughly about the distance between each tavern.

Some weary travelers reportedly left their tavern at sunrise only to return to that same spot at sunset. “Within the first mile,” a 1966 Toledo Blade retrospective noted, “his wagon might have been sucked down into the mud and it would take the rest of the day to get it out.”

One Michigan-bound settler ended up paying over one hundred dollars (roughly $3,500 today) to get his horse and wagon out of several mudholes. “He was still far from Perrysburg and he had no more cash,” authors Kathryn and Gordon Keller noted. “So he pulled up to the next mudhole, and there he quickly recouped his fortune by helping and collecting from other settlers slogging through.”

These taverns were sometimes little more than crude log cabins that, along with a place to sleep, would provide meals of racoon, possum, deer, or wild turkey—whatever the owner could shoot that day. A tavern’s meager grain crops provided feed for oxen and horses. Historian Nan Card notes, “warm fires and the ever-present whiskey jug made the mud, cold, and back-breaking misery almost bearable. At dusk, the taverns filled up quickly. Every available inch of space would be filled with exhausted families wrapped in mud-caked, damp blankets. Many were forced to sleep in their wagons or beside campfires.”

Mudholes were a major issue, and unverified accounts claim more than one person reported almost losing an entire horse in one. Nan Card points out that some travelers swore some mudholes’ depths “could only be measured by a ten-foot pole.” Tavern owners often made more money from pulling people from the mud than from innkeeping. Some were accused of watering the holes in front of their inns to bog down travelers so they’d be forced to stay the night. According to historian Prudence Dangler: “One tavern-keeper who had a particularly fine mudhole decided to leave the country. When he sold his business, he drew up a quit-claim and sold it for five dollars to a neighbor,” thus creating the nation’s first mudhole franchise.

When Charles Dickens skirted the Black Swamp, his editor G.W. Putnam was also along for the journey. Putnam’s account of the trip, later published in The Atlantic, described traveling through the swamp in greater detail than his literary-celebrity companion. Though we don’t know whether they were specifically on the Maumee and Western Reserve Road, his diary mentions traveling through an unbroken forest in Northern Ohio, just outside of Toledo, and also notes that it looked like a “wild and uncivilized territory.” Also, the road they travel upon sounds mighty familiar: “Holes nearly large enough to bury coach, horses, and all were constantly occurring,” Putnam wrote. “The driver managed with great skill to avoid them. It was a wondrous talent that put the wood and iron of that coach together, for it did not seem possible that it could long remain unbroken.”

Attempts at road improvement included corduroying the path by sinking logs into the mud until they hit bottom, and then stacking log atop log until a bumpy, ridged pathway (much like the texture of the fabric) emerged from the sludge. Most of the mud just absorbed logs as if it were bottomless. Half a century later, when an official road was finally built, engineers discovered perfectly preserved logs buried dozens of feet below ground. In some places, where the bedrock was near the surface, corduroyed roads did appear, which, oddly, made things worse sometimes. Dickens said a corduroyed road “is like nothing but going up a steep flight of stairs in an omnibus.”

“Mrs. Dickens had the back seat to herself; as the terrible jolting increased,” Putman wrote about his party transitioning from mudholes to corduroyed roads. “Mr. Dickens, taking two handkerchiefs, tied the ends of them to the door-posts on each side, and the other ends Mrs. Dickens wound around her wrists and hands. This contrivance, to which was added the utmost bracing of the feet, enabled the kind and patient lady to endure the torture of the ‘corduroy.’

“Mr. Dickens on his side, and I on mine, kept a sharp lookout ahead as well as we could, and when we saw — as we did almost every minute — an uncommonly large hole into which the wheels must go, we shouted, ‘Corduroy!’ and prepared ourselves for the shock. But preparation was of little avail, for with all our strength we found it impossible to keep our places, but were constantly tumbling upon each other and picking ourselves up from the bottom of the coach. At last we got through the swamp, and thankfully left the ‘corduroy’ behind us.”

Like Wile E. Coyote sitting down to a drafting table full of blueprints just after plummeting off a cliff, the brightest engineering minds of the era continued focusing their energy on the Great Black Swamp despite these failures. By 1850 builders asked, what’s the swamp’s greatest defense? The answer they came up with was its impossibly dense tree coverage. (Not the bottomless mud pits or malaria, or you know, murderous wolves. But we’ll let them have this one.) Thus, Ohio’s roadway engineers decided that they would just use the Great Black Swamp’s strengths against it like some kind of ecological tae kwon do match. Soon, an army of sawyers began slicing the land’s plentiful trees into planks and laying them into a smooth boardwalk along the Maumee and Western’s path. To everyone’s delight, this tactic actually worked.

Just about the time people got ready to celebrate, travelers found that this roadway was only wide enough for one wagon, so when meeting oncoming traffic, someone had to pull over — which inevitably left them stuck in the mud. Adding to the headaches, those planks began floating away during the first serious rains of the season. The boardwalk effort was abandoned after less than a decade, leaving the Maumee and Western Reserve Road in worse shape than ever.

Cut back to The Story of the Great Black Swamp. Glenn, in his nifty double-knit slacks, stands beneath a small bridge with a sad little Northwest Ohio creek running by his feet. You can find these puny streams all over the area. They have no plant or animal life, and their trickle of Yoo-Hoo-colored water tends to only transport Styrofoam cups and candy wrappers from one end of town to the other, especially back in Glenn’s prerecycling era. Prior to living in Oregon in the early 2000s, I thought this was what normal looked like everywhere, before learning creeks and rivers were not meant to be liquid dumpsters and that natural bodies of water are often clear — with fish living in them!

“A similar attempt to get over the swamp if one couldn’t get through it was made by the Ohio Railroad Company in the 1830s and 1840s,” says Glenn. The camera continues its slow zoom out, and surprise, Glenn has been standing beneath a rusted iron railroad bridge this whole time. I understand where he’s going with this one. This was the Industrial Age! There was no place on Earth where tracks hadn’t been laid. No mountain or tundra or desert where steam engines couldn’t plow forward. Manifest Destiny, ahoy!

Once again, humans used the swamp’s own trees as weapons. The railroad planned to build a long, elevated train bridge from Sandusky City to Maumee Bay, hovering above its muck and hungry wolves via a series of trestles. The job required a steampunk-looking contraption that was essentially a train engine that featured a buzzsaw at the end of a long mechanical arm. The idea was that this cartoonish machine would cut down trees and feed those logs back to a traveling sawmill that followed the buzzsaw, which instantly converted this fresh wood into the trestles and rail ties that would then be built in its wake.

A weekly paper in Toledo at the time wrote: “It is wonderful and marvelous to see such a thing of wood and iron and fire and water, walking deliberately and safely, and almost intellectually, over the deep morasses of the Black Swamp, apparently by its own volition, making its own road as it passes.” Optimistically, this writer guessed that “nine months will enable us to travel the far-famed Black Swamp in less than two hours.”

Not bad, reducing a thirty-one-day trek through Hell down to a pleasant couple of hours. This, surely, would end the Great Black Swamp’s reign of terror.

Glenn steps up from that nasty creek bed and onto some train tracks. Directly behind our host is my personal Golden Gate Bridge, Statue of Liberty, and Epcot Center all rolled into one. For a fragment of the film, I spot the most recognizable monument of my hometown: A mint green water tower with DESHLER painted in huge black letters across its face.

Prior to watching The Story of the Great Black Swamp, I have never seen my hometown on television. If discovering a whole documentary had been made about Northwest Ohio was a surprise, seeing Deshler onscreen is a stunner. I didn’t even know a professional camera crew had ever set foot within the city limits. Forty years later, it’s still thrilling, magical, and unexpected.

In the Jerome Library’s AV room, a huge, glowing smile appears on my face as I remember that I have stood beneath that same water tower as Glenn. He’s right beside the town reservoir, the largest body of water for twenty miles in every direction, the place where, while on summer break, my friends and I would ditch our bikes and run along the tracks to yell “Water!” to train engineers as their giant diesel engines puttered past. More often than not, an itty-bitty six-pack of waters flew from the open window — barrel-shaped plastic bottles with pull-off aluminum foil lids that looked like the corn-syrupy Kool-Aid knockoffs “Little Hugs,” but the liquid was crystal clear. We’d all have a gleeful gulp, not because we were thirsty, but because in 1980s Northwest Ohio we’d never seen bottled water before.

When I refocus on Glenn, he’s describing how this Black Swamp railway endeavor quickly went all to Hell. If you guessed metric tons of wooden trestles and steel tracks were spaghetti-slurped into the swamp, you are officially smarter than an 1800s railroad magnate. Bravo! The film plasters up embarrassing photos of buried tracks poking from the mud like a sunken xylophone. “By 1845, the Ohio Railroad Company was bankrupt,” Glenn says. “The swamp had won again.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Great Black Swamp: Drained centuries ago, DNR and Ohio organizations look to bring some of it back

From the Ice Age to Now: A Lake Erie timeline

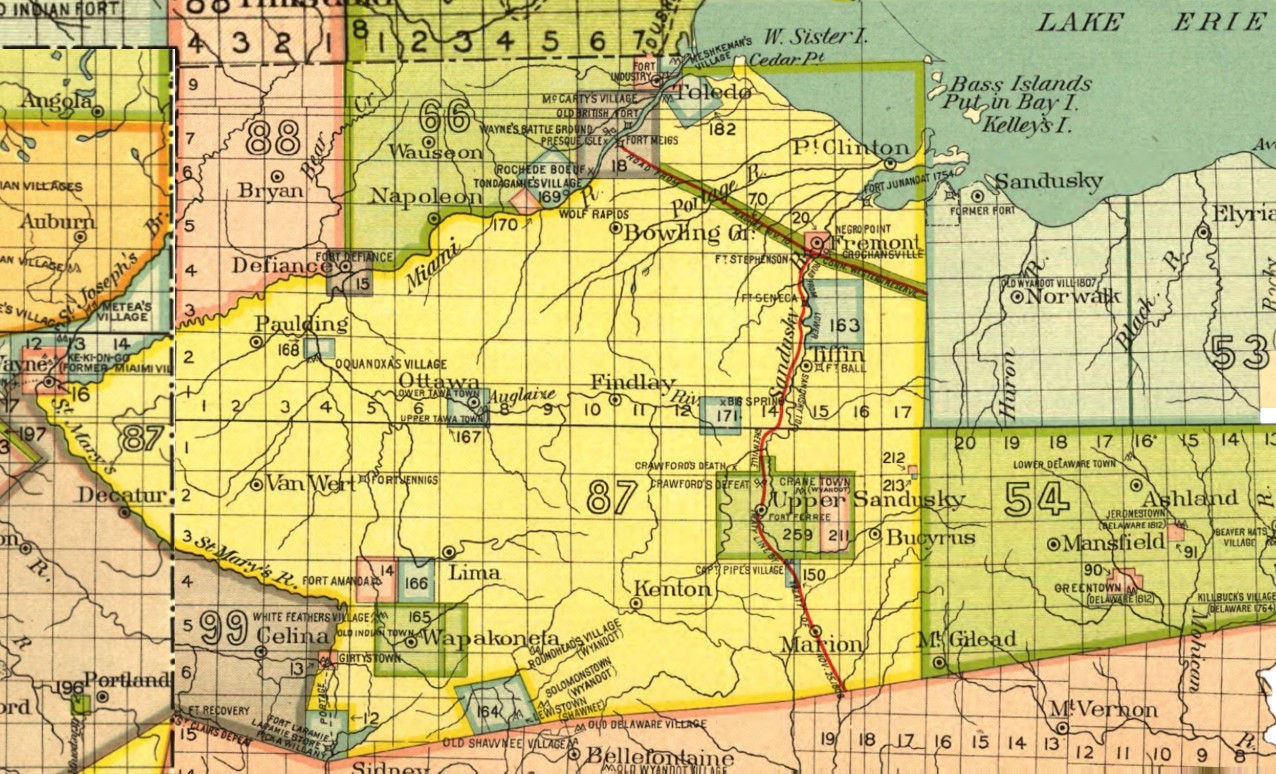

Featured image: This image from 1899 combines the Indian Land Cession maps covering parts of Indiana, Michigan and Ohio — the Great Black Swamp covered most of the yellow part of this map. Photo from National Archives. (Photo Credit: Library of Congress)