“Wrecked: The Edmund Fitzgerald and the Sinking of the American Economy” is a new book by Thomas Nelson with Jeremy Podair. Below is an adapted excerpt from the chapter “Just Call Toby,” that details the legal mess families were put through after losing their loved ones on the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The families of the sailors of the Edmund Fitzgerald do not like to talk about their insurance settlements with Ogilvy Norton Corporation.

“It’s a sore subject,” Deborah Champeau, daughter of Third Assistant Engineer Oliver Champeau told me.

And for good reason. Despite their fathers, husbands and sons being in the same boat — literally and figuratively — the settlement amounts were as wide ranging as the random, roaming waves of Lake Superior itself. Of the family members and attorneys I spoke with, settlements ranged from $25,000 ($122,000 in 2023) to almost half a million dollars ($2.4 million in 2023). While inherent factors such as age and earning potential figured high in calculations for settlements, the range of payments were well beyond any disparities due to these considerations.

Payments were settled between a few months after the ship’s sinking and as late as 1982. By the latter date the country was facing its worst levels of inflation in thirty years. In the six-year period between 1976 and 1982, inflation shot up a staggering 76 percent. Payouts in 1982 would thus have had to be nearly twice as much to match the settlement amounts made at the beginning of the ordeal.

Earlier in the decade as momentum was gaining for laws to protect natural resources and keep communities healthy and workplace protections through the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), the movement for tort law reform with this express intention of discouraging lawsuits against negligent corporations — perhaps a Great Lakes freight shipping company — was building steam. The modern-day tort reform movement began in the 1970s, a campaign that was largely underwritten by corporations, particularly insurance companies.

Insurance companies were not interested in torpedoing claims one by one — whole floors of claims agents took care of those nuisances — but by overhauling “public perceptions” and pushing hard for “legislation limiting personal injury lawsuits.” Consumer advocate Ralph Nader — who earned national acclaim for his book “Unsafe at Any Speed,” which exposed the auto industry’s shoddy safety record — was in full gear pushing back on tort reform movement, earning him the moniker from opponents as a “one-man cheering squad for tort law” as if he and he alone would benefit from consumer protections. His legacy would continue well into the next century.

Legal Loopholes

Families could be sorted into two groups: those with legal representation and those without. Given the modest backgrounds of the families who had little to no access to high-powered legal expertise, most struck out on their own. Ogilvy Norton Corporation exploited this reality to maximum effect. The disparate payouts proved it. Those without representation settled quickly and signed nondisclosure members who had representation. small settlements. agreements. agreements. They received considerably less than widows and other surviving family members who had representation.

As soon as word got out that some families received more than others, those without attorneys sought out legal representation. But it was too late. These family members were turned away from law firms because they had signed agreements with Ogilvy Norton Corporation and/or Northwestern Mutual that precluded them from recovering any more damages. This was also the case for families that worked with attorneys with limited maritime law experience, who signed off on relatively small settlements.

Maritime law is a two-hundred-year-old body of law that is weighted against workers and consumers. In the nineteenth and even eighteenth centuries, the fledgling U.S. government, seeking to encourage investment in trade, imposed legal limits on carrier liability. And while laws that govern other industries like rail have evolved as the inherent dangers of the work have been recognized, maritime law has not changed one iota.

Unlike in the rail, steel, or paper industries, when workers are hurt — or in the case of the sinking of the Fitzgerald, perish — victims and their families must meet a high burden of proof before companies must take responsibility and pay up for damages.

The fundamental question of responsibility is whether a sinking was due to negligence on the part of the captain or crew or whether it was due to unseawor-thiness of the ship. If the vessel sinks because of negligence, damages are limited to the value of the ship and cargo, which are at the bottom of a lake or ocean. British common law, the basis of American maritime law and all U.S. federal law, pegged the value of a sunken ship at “two pence,” the equivalent of two American cents. For the purposes of this case, however, Ogilvy Norton Corporation and Northwestern Mutual were a bit more generous and pegged its value at $817,920. However, if the ship sinks because it was not seaworthy, and should never have sailed in the first place, the damages are unlimited.

It was this question that drove early inquiries surrounding the nature of the Fitz’s demise. It remains a compelling question among history buffs, divers, maritime enthusiasts and family members who are consumed by the tragedy. It is a big reason for the enduring legacy and mystery surrounding the wreck. But among lawyers involved in the cases it quickly became a moot point, for the simple reason that neither side wanted to take the case to court.

For Ogilvy Norton Corporation, theirs would be a tough case to defend in court, and they knew it. The facts spoke for themselves. A ship sank and twenty-nine sailors died. In the legal world it was considered “res ipsa loquitur” (the thing speaks for itself) or, in lay terms, it was a slam dunk. for itself) or, in lay terms, it was a slam dunk.

Northwestern Mutual wanted their name out of the newspapers. (It didn’t help that the boat was named after a company CEO.) They had customers to keep happy. It wasn’t good for business if an insurance company was part of a high-profile story in which policy holders on deceased victims were being denied or cheated on legitimate claims. At first, Haskell seemed to recall, Northwestern Mutual would not even acknowledge to the families that their ship had sunk.

“Everybody was saying, ‘Okay, where is it then?’ If it isn’t their ship that went down, where is their ship?” James Haskell, little brother of Second Assistant Engineer Russell Haskell, told me. “And three or four days later they said, yep it was the Fitzgerald that went down.”

Ogilvy Norton Corporation was also slow to inform the families of the tragedy. At the same time, they were getting families to accept insultingly low payouts and sign gag orders. The company was desperate to save face and money, even though it had posted record profits for 1975.

The families wanted the whole matter put to rest so they could try to get on with their lives. Plus, they could use the money. For most of these families, their loved one who died was the household’s only breadwinner. “Breadwinner liberalism,” as Robert O. Self named it, developed in the nineteenth century. This way of life segmented out male and female household roles. Men’s work was “remunerative, family sustaining,” while the female was the “caregiver” typically without remunerative work. In other words, the best a sailor’s family could hope for in the 1970s was a well-funded nineteenth-century family model. Families immediately found themselves without an income stream, and good paychecks in the Northwoods were hard to come by.

Healthy paychecks were so rare in Superior and a large swath of northern Wisconsin that when sailors married young, jealousy would abound among their former dependents, such as siblings or parents. Fights between wives and in-laws over money would ensue. An already harried family life where fathers, husbands, and sons were away from home eight months out of the year, missing birthdays, graduations, anniversaries and holidays, would destabilize home life even more. The families needed a champion.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

In “The Gales of November,” author John U. Bacon investigates the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Has this freighter made its final voyage?

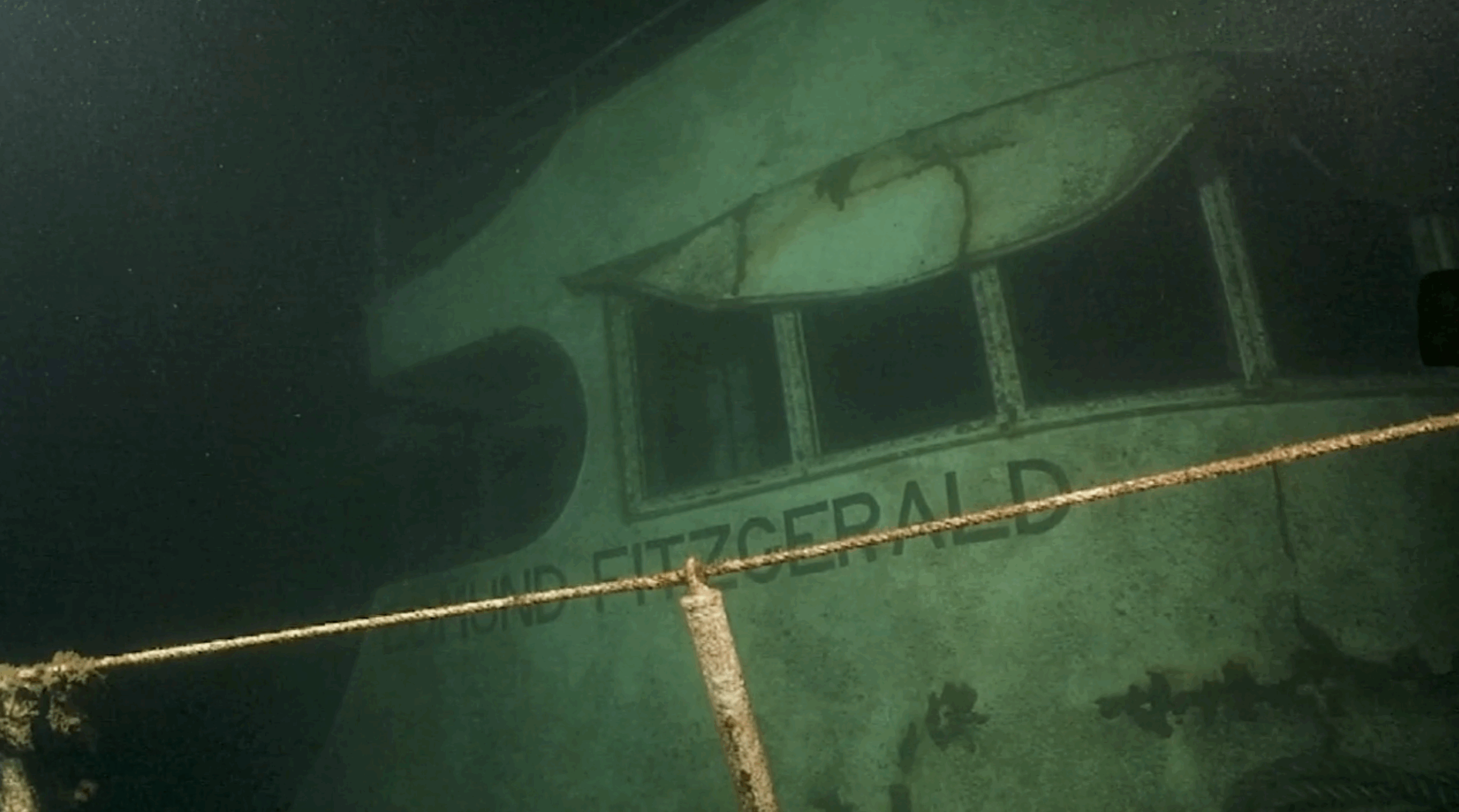

Featured image: Edmund Fitzgerald. (Photo Credit: Great Lakes Now)