Watching how fish move, how they use the water to their advantage has made me a better diver. Underwater, I strive to be as trim as a walleye and as effortless as a sturgeon. And while my cameraman husband hunts for photo ops with the stealth of a muskie, I can usually be found frolicking in the shallows like a carefree sunfish.

My goal when diving is to be like the fish.

Even if I can’t outswim a guppy in a fishbowl, I have picked up a few tricks along the way about how to be more at ease in the water and in life.

When it comes to efficiency and speed, it’s hard to beat the sleek form of a pike or walleye. Their torpedo-shaped bodies enable them to go from hovering to gone in the blink of an eye. Their fins and tails are not billowy or showy. Rather they have short tight fin rays for minimum resistance with maximum thrust.

Like walleye, the more streamlined or trim I make myself when diving, the more efficiently I can move underwater. And, just as important, the trimmer my gear is the less likely I am to get tangled up.

It only takes one protruding hose or dangling cord for a diver to get snagged, and in a heartbeat the dive goes from an enjoyable adventure to a life-threatening situation.

Before every dive I make sure my gear is snug, secure and as trim as a pike.

In general, the deeper an object travels in the water the heavier it becomes. This is true for both divers and fish.

Manistee River sturgeon (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Most fish have a small internal organ called a swim bladder that they can inflate or deflate at will. They add air as they go deeper in the water column to keep themselves buoyant, and they vent air when they come back up.

Fish can’t swim without a swim bladder.

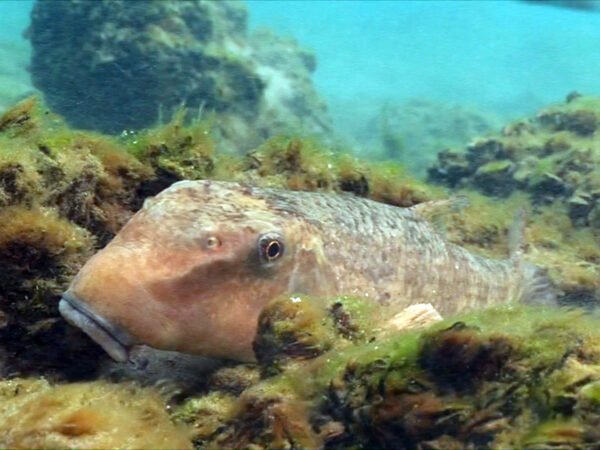

Round gobies are a good example. They zip and dash around the bottom like race cars. But they couldn’t pass a lifeguard test, because without swim bladders they can’t actually swim the length of an Olympic-sized pool without touching the bottom.

Wreck and cave divers are particularly conscious of their buoyancy. In these environments, a touchdown by a heavy diver can disturb decades of fine sediment which will quickly drop the visibility to zero. It’s a great way to ruin a dive and turn a fun day deadly.

Like the fish, divers have to adjust their buoyancy throughout the dive. As we go deeper, the increased pressure squeezes the air out of our wetsuits like water from a wrung sponge. To compensate, we add air to our buoyancy control vests. When we return to shallow water, our suits plump back up and we have to purge air from our vests least we pop to the surface like corks.

When diving in ponds or inland lakes with squishy soft bottoms, having good buoyancy control keeps us from mucking up the bottom and ruining any filming opportunities for hours or even days.

I envy the fish as their swim bladders are fully automated while our vests are strictly manual. Still, as I move through the water column, I strive to balance my buoyancy with the smooth automation of a fish.

When it comes to emulating fish, I have no delusions of ever being able to mimic the movements of an adult lake sturgeon.

An adult lake sturgeon can zip upstream against a 4-mph current with barely a flick of its tail. They spawn during the spring when rivers are swollen and moving at maximum speed.

While those conditions are ideal for mature adults who could theoretically swim up to the base of Niagara Falls without breaking a sweat, it’s more challenging for their offspring – and wannabe divers like myself.

Unless they are spawning, the adults rarely settle on the bottom. They feed by swimming a few inches off the bottom, and many times I’ve seen them hovering a few feet off the bottom. But I’ve never seen an adult actually resting on the bottom.

In contrast, juvenile lake sturgeon spend the first year of their lives sticking as tightly to the river bottom as possible. It offers many advantages to the young fish.

By keeping their bellies tight to the bottom, the river water is forced to flow up and over their bodies. As it passes over them, the water exerts a downward force which essentially pins the fish to the bottom. This hydrodynamic effect allows the little fish to remain in place on the bottom in the strongest of currents with almost zero effort.

When I watch juvenile lake sturgeon maneuver around the river bottom, I’m reminded of whitewater kayakers in a class five rapids. Both ride ragging rivers with ease. They skirt from side to side at will, working the riffles and chilling in the eddies.

A popular and frequently executed maneuver in canoeing and kayaking is called a ferry glide. It’s a technique whereby a paddler can go from one side of a river to the other without really having to paddle. When executed properly, the river basically pushes the vessel to the other side.

Young-of-year sturgeon are masterful river gliders. They move across the bottom not by swishing their tails frantically but by angling their fins and harnessing the energy of the river to glide wherever they want to go. Like everything they do, it appears completely effortless.

I’ll never be good enough underwater to hover on a sturgeon spawning site like an adult nor do I ferry glide across the bottom with the grace of a juvenile, but I do use my modified version of the technique on almost every river dive I make.

The fish have shown me how the water can lift me up, how it can help to get me where I want to go. It can hold and support me. Or it can kick my ass. It just depends on how I approach it.

Emulating fish has definitely made me a better diver, but I honestly believe they’ve made me a better human too. I never imagined that I could learn more about genuine teamwork and personal sacrifice from watching schooling shiners than in my group dynamics course at university.

But I did.

And I’m eagerly anticipating my next lesson.

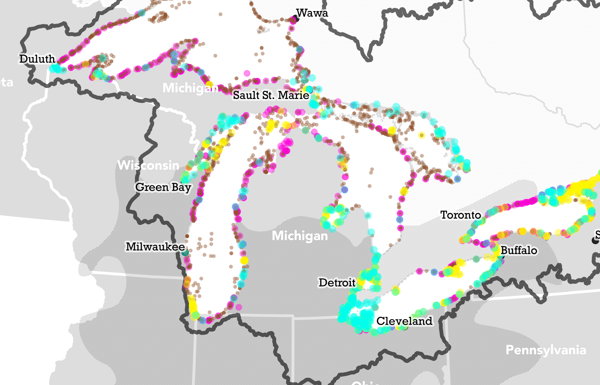

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Sturgeon Restoration: Starting anew in Sturgeon and Saginaw bays

Sturgeon Restoration: Streamside hatcheries on the Manistee, Milwaukee and Maumee rivers

Featured image: Gobies (Image from PolkaDot Perch)

3 Comments

-

Many fish species lack swim bladders and can swim long distances. Examples are lingcod (found off the California coast) and many other bony fishes as well as sharks and rays. Think about doing some research before writing your next bit of information.

-

Easy Mike, think about showing some tact before displaying your next bit of insolence.

-

-

I just love Kathy’s work she is doing. I find it so important to see what our mysterious lake hold for aquatic life. What gorgeous fish to behold and seeing them in their ecosystem. I to am an ex Navy diver and love to e ploe my favorite elusive fish of the east coat. The Wolf Fish…now on the extinction list. I find this very sad. Such an interesting beast. Since 1995 I have noticed the massive decline in them. Thank you Kathy for your informative sessions. Keep in touch. Keep up the good work Brian.