Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

There’s a connection between Great Lakes cleanup and economic and community revitalization, a connection that’s outlined in a report titled “Great Lakes Revival,” recently released by the International Association for Great Lakes Research.

Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River is infamous for catching on fire in 1969, when few, if any, fish were living in the river. Today, thanks to coordinated cleanup efforts, you can find 70 species of fish, and peregrine falcons, bald eagles, and osprey have returned to the banks.

Cleveland’s Flats was ground zero of the industrial revolution and this water pollution. Today, the Flats is a unique urban neighborhood where nature, commerce and industry live together. Since 2012, the Flats has experienced $750 million in economic development, with another $270 million in the planning phase.

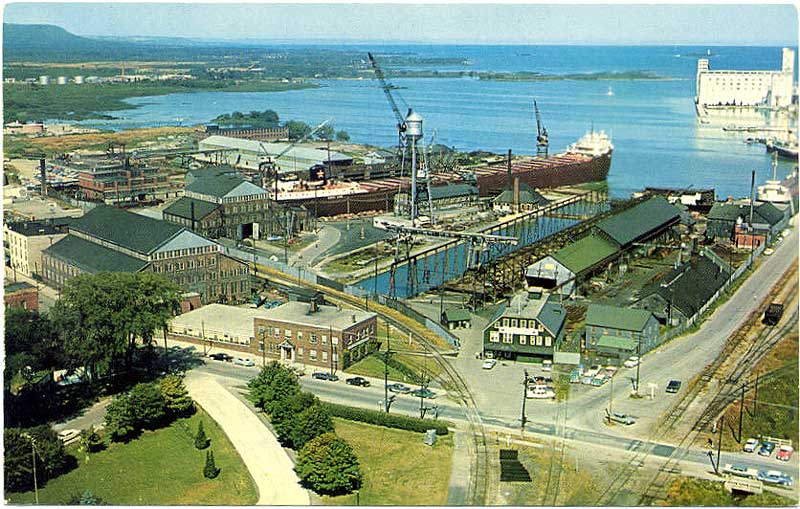

In the 1960s, the Buffalo River in Buffalo, New York, was described as a repulsive holding basin for industrial and municipal wastes and was devoid of oxygen. For at least four decades, starting in the 1920s, no fish were found in the river. Cleanup of the river has led to a surprising ecological revival.

Buffalo River, before cleanup to reviitalize and draw people to the riverfront. Photo by Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper via John Hartig

Today the Buffalo River restoration has been a catalyst for creating waterfront public spaces in Buffalo, New York, Photo by Joe Cascio via John Hartig

Today, you can find 25 to 30 species of fish, and peregrine falcons are reproducing after an absence of more than 30 years. The river cleanup spurred increasing public access to the water, which has in turn contributed to waterfront economic revitalization, including more than $428 million of waterfront development between 2012 and 2018.

For more than 100 years Collingwood Harbour on Georgian Bay, Ontario, was a ship building center for Canada. Harbor cleanup was initiated in 1985 and eventually included upgrading the sewage treatment plant, remediating contaminated sediment, rehabilitating habitat and cleaning up brownfields. The shipyards closed in 1986 and sat vacant for nearly 20 years as an abandoned brownfield site.

The Collingwood’s shipyards circa early 1960s with the freighter Carol Lake, built by Collingwood Shipyards, Ltd. in 1960, Photo by William Forsythe Boatnerd.com via John Hartig

Today the Shipyards are a European-inspired, waterfront development with more than 600 homes, Photo by FRAM Building Group via John Hartig

The cleanup of Collingwood Harbour catalyzed the transformation of the abandoned shipyards into a mixed-use waterfront community with more than 600 homes, a waterfront promenade and park, a community amphitheater and hiking trials that will link to the Georgian Trail.

In the 1960s, the Detroit River was one of the most polluted rivers in North America. Oil pollution was killing winter waterfowl, phosphorus pollution accelerated enrichment of Lake Erie, municipalities and industries violated water quality standards, toxic substances contamination was causing both fish consumption advisories and reproductive impairment in wildlife, and land use practices destroyed wetlands.

Public outcry incited cleanup of the river. This cleanup of the Detroit River has resulted in one of the most remarkable ecological recovery stories in North America.

In the late 1960s, when the Detroit River was one of the most polluted rivers in North America, no bald eagles, peregrine falcons or osprey reproduced in the Detroit River watershed, nor lake sturgeon or lake whitefish in the river. Beavers had disappeared, as had the common terns from the 980-acre island park Belle Isle. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission considered walleye to be in a state of crisis.

The Detroit riverfront east of the Renaissance Center as recently as the early 2000’s, Photo by Detroit Riverfront Conservancy via John Hartig

Today the Detroit RiverWalk is one of the largest, by scale, urban waterfront redevelopment projects in the United States, Photo by Detroit Riverfront Conservancy via John Hartig

Today, bald eagles, peregrine falcons, osprey, lake sturgeon and lake whitefish are reproducing again, beavers have returned, common terns are back, and the Detroit River is now considered part of the “Walleye Capital of the World.”

Over time, Detroit lost people and industries, and there was much underused and undervalued riverfront land. Detroiters had long lost their connection to the Detroit River. With the revival of the river, people wanted to improve public access to it and redevelop it in a fashion that would improve quality of life, catalyze economic development and help change the perception of Detroit from that of a Rust Belt city to one that is actively engaged in sustainable redevelopment.

Out of this growing public interest to reconnect to the Detroit River, the ecological recovery, and strong public and private support to revitalize Detroit, the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy was created in 2003 to transform Detroit’s international riverfront into a beautiful, exciting, safe, accessible world-class gathering place for all. Over 3.5 miles of the Detroit RiverWalk are now complete. An investment of $80 million in building the Detroit RiverWalk in the first 10 years has returned over $1 billion of public and private sector investments. Nearly three million annual visitors are already using it.

The 10 case studies presented in “Great Lakes Revival” show that Great Lakes cleanup is not just a cost, but an investment. Sustained Great Lakes funding should be viewed as an investment in revitalizing communities and economies as part of a strategy to achieve a blue economy with competitive advantage.

Featured Image: Cleveland skyline from the Flats, Photo by Erik Drost via wikimedia.com cc 2.0

Editor’s Note: Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. The “Great Lakes Revival” study was funded by Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation, which also is a funder of Great Lakes Now.