Piers, beaches marinas at risk

When you hear “tsunami,” what comes to mind?

Likely the tsunami that hit Japan in 2011 and took over 10,000 lives and caused economic damage in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

The Japan tsunami was caused by a seismic – earthquake – event and the Great Lakes region is mostly immune to earthquakes.

But the Great Lakes aren’t immune from another type of tsunami, a meteotsunami. “Meteo” derived from meteorology — weather.

That was the topic of a group of researchers gathered in Ann Arbor this week to highlight the relatively unknown dangers of tsunamis caused by a perfect storm of weather conditions.

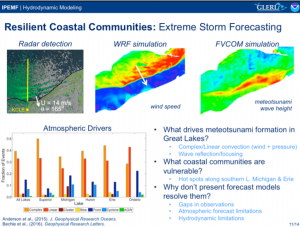

Meteotsunamis are significantly smaller events than their ocean-based counterparts and are generated by rapid changes in barometric pressure associated with fast-moving weather systems. Mid-westerners have seen intense summer storms quickly move along the horizon that bring strong winds and wide temperature swings in a short time period.

Those conditions can be the genesis of meteotsunamis.

Many meteotsunamis are undetected events but they can be significant like the one that capsized a tugboat in White Lake bordering Lake Michigan in 1998.

Or the 2003 weather incident that killed seven near Sawyer, Michigan. The deaths were originally attributed to riptides but subsequent investigation suggests the more likely cause was a meteotsunami.

Most at risk from meteotsunamis are people on “piers, swimming at the beach, boats near the coastline, and marinas,” Eric Anderson told Great Lakes Now.

He says meteotsunamis can occur in any of the Great Lakes but based on limited research to date, southern Lake Michigan and Lake Erie are the lakes most at risk.

Anderson is a researcher at the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) and is part of a multi-disciplinary team trying to raise awareness of the need for a meteotsunami warning system.

The stakes are high says University of Michigan’s Dr. Brad Cardinale.

“Developing a warning system for meteotsunamis is a matter of life and death,” according to Cardinale who directs the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research.

“No apparent local reason”

Grand Haven, Mich. charter boat captain Denny Grinold has been on the lakes since 1973 and said he has experienced large lake swells that occur for “no apparent local reason.”

Grinold says he never thought of calling them a tsunami but “accepted that the condition was due to storm action or pressure differences in another area of the lake.”

The threat to lake freighters is “less dramatic than to small boats,” researcher Anderson says. Though they could be impacted in harbors where they might be subject to grounding.

Glen Nekvasil from the industry group the Lake Carriers Association told Great Lakes Now he had “never heard the term meteotsunamis,” but said “our ships have a number of weather forecasting resources and were built to operate in storms…”

Anderson says beach managers are accustomed to posting warnings for riptides but for marina and harbor managers, “a different or additional communication strategy may be warranted” due to the risk of boats capsizing.

The U.S. Coast Guard Station in Milwaukee responsible for Lake Michigan didn’t have an immediate familiarity with meteotsunamis but referred Great Lakes Now to the district office in Cleveland which didn’t respond by deadline.

GLERL’s Anderson said he isn’t surprised that the Coast Guard isn’t familiar with the term “meteotsunami” as it’s “relatively new terminology for the Great Lakes.” He said the Coast Guard is familiar with the conditions “which are often mis-classified as storm surge or seiche or even freak waves.”

Great Lakes Now recently reported that drownings in general in the Great Lakes spiked by 78 per cent from 2015 to 2016.